An American astrophysicist, Andrea Ghez, was awarded the Nobel Prize in physics on Tuesday for discovering that stars at the center of galaxies are hurtling through space around supermassive black holes.

Ghez, shares half the prize with German astrophysicist Reinhard Genzel, who independently observed the astonishing acceleration of the star at the galactic center. Astrophysicists now believe that supermassive black holes are at the center of all galaxies and played a role in the formation of galaxies from the soup of primordial matter in the early universe.

The other half of the prize went to Roger Penrose, a British mathematical physicist who is cited for his discovery that the existence of black holes is one of the strange implications of Albert Einstein’s theory of general relativity, in which gravity is associated with the curvature of space and time.

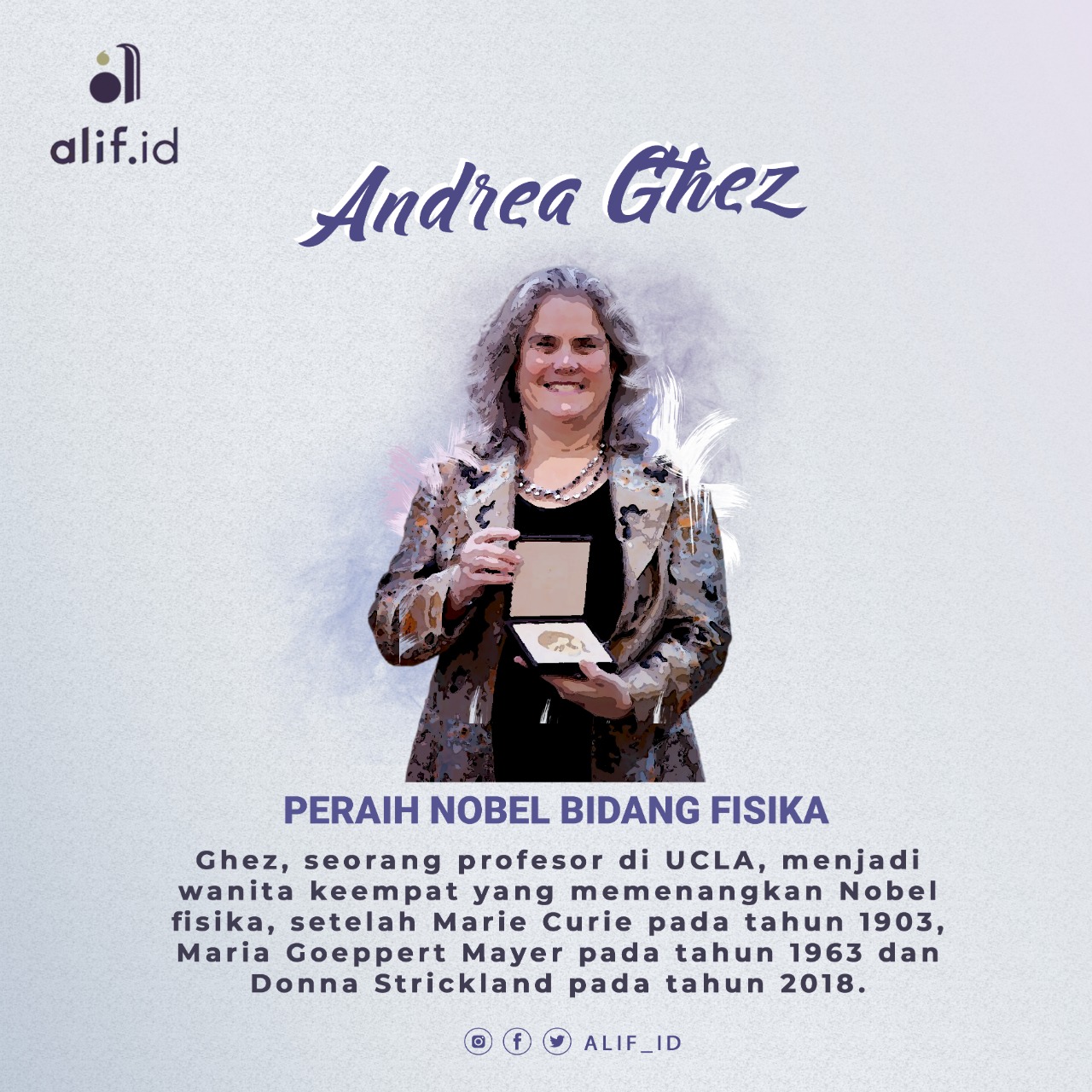

Ghez, a professor at UCLA, became the fourth woman to win the Nobel Prize in physics, after Marie Curie in 1903, Maria Goeppert Mayer in 1963 and Donna Strickland in 2018.

The secretary general of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, called Ghez to inform him that he had been awarded. About an hour later, she spoke by telephone to reporters in Stockholm, discussing the thrill of her research and her hopes that this new recognition would inspire more women to enter the field of physics.

Asked what he thought when he first saw signs that something mysterious was lurking in the center of the galaxy, he said: “I think the first thing was doubt. You have to prove to yourself that you really see what I think and I see. “Doubt and excitement.”

Ads – Continue Reading Below

–

He added, “We don’t know what’s inside black holes, and that’s what makes these objects such exotic objects.”

Ghez has received many awards, including a “genius” award from the MacArthur Foundation. She was the first woman to receive the Crafoord Award from the Royal Swedish Academy. A graduate of MIT, where he majored in physics, and the California Institute of Technology, where he received his doctorate, he has been on the UCLA faculty since 1994.

“I take the responsibility of being the fourth woman to win a Nobel Prize very seriously. “I hope I can inspire other young women. It’s a field where there’s so much fun, and if you like science, there’s a lot to do.”

This year’s Nobel Prize in physics honors the theoretical side of black holes and the observational side, the investigations of Ghez and Genzel. There is no short list for a Nobel laureate, and the winners only find out they’ve won only when they get an early morning call from Sweden. This year, as has happened in the past, the announcement was postponed while the academy attempted to reach one of the winners.

The fact that this year’s prize will somehow involve black hole physics was hinted at by Hansson in his opening statement: “This year’s prize is about the universe’s darkest secrets.”

The normally crowded halls of the academy have been largely empty amid the restrictions imposed due to the coronavirus pandemic. Hansson said this year there would be no live Nobel celebrations in Stockholm in December.

In announcing the prize, the academy cited an article Penrose wrote in 1965, a decade after Einstein’s death, in which he said black holes really did exist. “His groundbreaking article is still considered the most important contribution to the general theory of relativity since Einstein,” the academy wrote.

University of Chicago physicist Michael S. Turner on Tuesday called Penrose “a brilliant mathematician who turned his prodigious skills into understanding Einstein’s theories at a time when there were doubts even about the mathematical reality” of black holes.

Turner said Einstein did not fully understand the implications of his own theory. “It took another generation of brilliant physicists to figure it all out, not because of Einstein’s limitations but because of the richness of his theory,” Turner said.

Black holes are one of the strangest features in the universe. They are formed from collapsing stars, with their matter compressed by gravity so that, according to the equations of general relativity, space becomes infinitely curved. Light can’t escape gravity very well. In 2019, scientists revealed the first direct images of a supermassive black hole at the center of Messier, a galaxy in the constellation Virgo.

Ghez, supported by a team of researchers and using some of the world’s largest telescopes, separately published findings in the 1990s and 2000s that provide observational support for the existence of a supermassive black hole or something suspicious in the center of our own galaxy in the region known as Sagittarius. .

The extraordinary speed at which stars move in the region suggests that they are affected by the gravity of the supermassive object. What the object is, exactly, is unknown, but as the Swedish Academy put it when announcing the prize, “supermassive black holes are the only known explanation at this time.”

Even though they weren’t observing black holes directly, they were instead examining individual stars whose movement implied the presence of something creating a strong gravitational field. Our sun fully orbits the galaxy for about 230 million years, but near the galactic center, some speed demon stars have orbits of less than 20 years, including one of the 11.5 years described in a 2012 paper in the journal Science co-authored by Ghez.

The mysterious “something” at the center of the galaxy appears to have a mass equivalent to 4 million suns.

Observing the stars at the galactic center is technically challenging, even with the large telescopes used by Ghez in Hawaii and Genzel in Chile. The galactic core is full of stars, and scientists need to pick out individual stars in the middle of the swarm. The distances involved are enormous – about 26,000 light years – and the motions of the distant stars are difficult to detect. Observations take years, even decades.

The abundance of dust interferes with vision, so scientists have to observe the part of the near-infrared spectrum that penetrates the dust. And they had to find a way, through what’s known as adaptive optics, to correct the distortion created by Earth’s atmosphere.

Tuesday’s announcement came as a shock to the physics community, simply because the academy typically rotates prizes through a wide area of fields, covering everything from the smallest subatomic particles to the vastness of the universe. But for the second year in a row, the academy honors work in cosmology and astrophysics.

–