But of all the colors found in rocks, plants and flowers, or in the fur, feathers, scales and skins of animals, blue is extremely rare. But why is blue so rare? The answer comes from the chemistry and physics of how color is produced — and how we see it.

We can see color because each of our eyes contains between 6 million and 7 million light-sensitive cells called cones. There are three types of cones in the eye of a person with normal color vision, and each type of cone is most sensitive to a specific wavelength of light: red, green or blue.

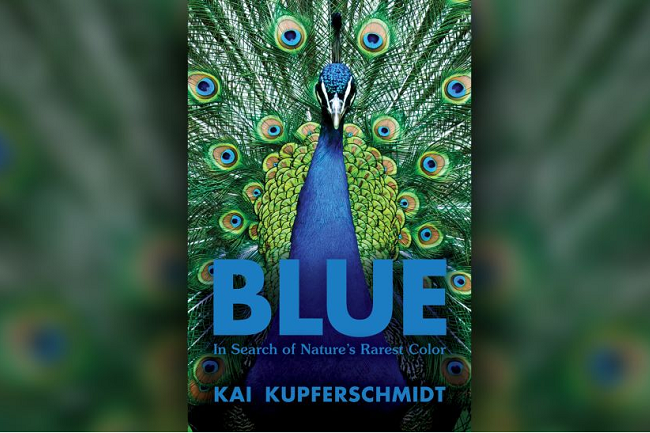

“When you look at blue flowers — for example, cornflowers — you see cornflowers blue because they absorb the red part of the spectrum,” Kupferschmidt said. In other words, the flower appears blue because that color is part of the spectrum that the flower rejects, writes Kupferschmidt in his book, which explores the science and nature of this popular hue.

In the visible spectrum, red has a long wavelength, meaning that it is very low in energy compared to other colors. For a flower to appear blue, “it must be able to produce molecules that can absorb very small amounts of energy,” to absorb the red portion of the spectrum, Kupferschmidt said.

Generating such molecules — large and complex — is difficult for plants to do, which is why blue flowers are produced by less than 10% of the world’s nearly 300,000 flowering plant species. One possible driver for the evolution of blue flowers is that blue is highly visible to pollinators such as bees.

Blue flowers can benefit plants in ecosystems where competition for pollinators is high, Adrian Dyer, a professor and vision scientist at the Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology in Melbourne, Australia, told Australian Broadcasting Company in 2016.

As for minerals, the crystal structure interacts with ions (charged atoms or molecules) to determine which part of the spectrum is absorbed and which is reflected. The mineral lapis lazuli, which is mined mainly in Afghanistan and produces ultramarine pigmen a rare blue, containing a trisulfide ion — three sulfur atoms bonded together in a crystal lattice — that can lose or gain an electron. “It’s the energy difference that makes blue,” says Kupferschmidt.

–

The blue color of animals does not come from chemical pigments. Instead, they rely on physics to create the blue look. Blue-winged butterflies in the genus Morpho have intricately layered nanostructures on their wing scales that manipulate light layers so that some colors cancel each other out and only blue is reflected; a similar effect occurs in the structures found in blue jay feathers (Cyanocitta cristata), blue tang scales (Paracanthurus hepatus) and a venomous blue ring octopus flashing ring (Hapalochlaena maculosa).

Shades of blue in mammals are even rarer than in birds, fish, reptiles, and insects. Some whales and dolphins have bluish skin; primates such as the golden snub-nosed monkey (Rhinopithecus roxellana) has a blue skinned face; and mandrills (Mandrillus sphinx) has a blue face and a blue back end.

But fur – a trait shared by most land mammals – is never naturally bright blue (at least, not in visible light. Researchers have recently discovered that platypus fur glows in vivid shades of blue and green when exposed to ultraviolet light ( UV), Live Science previously reported.

“It took a lot of effort to make this color blue, and another question becomes: What is the evolutionary reason for making blue? What’s the incentive?” said Kupferschmidt. “The interesting thing when you dive into this animal world is always, who is the recipient of this message and can they see the color blue?”

For example, while humans have three types of light-sensing receptors in our eyes, birds have a fourth type of receptors for sensing UV light. Feathers that appear blue to the human eye “actually reflect more UV light than blue light,” explains Kupferschmidt. For that reason, the bird we call the blue breast (Cyanistes caeruleus) “would probably call themselves ‘UV boobs,’ because that’s what most of them see,” she says.

–

Due to the rarity of the color blue in nature, the word ‘blue’ is relatively late for languages around the world, appearing after the words for black, white, red and yellow, according to Kupferschmidt.

“One theory for this is that you really only need to name a color after you can color something – once you can separate a color from the object. Otherwise, you don’t really need a name for the color,” he explains. “Dyeing things blue or finding blue pigment happens very late in most cultures, and you can see that in linguistics.”

The brilliant blue feathers of a bird, like a macaw Spix (Cyanopsitta spixii), gets its color not from the pigment but from the structure of the feathers that scatter light.

The earliest use of blue dye occurred about 6,000 years ago in Peru, and the ancient Egyptians combined silica, calcium oxide and copper oxide to create the long-lasting blue pigment known as irtyu to decorate the statue, the researchers report Jan. 15 in the journal.

Frontier in Plant Science, ultramarine, the bright blue pigment soil of lapis lazuli, is as precious as gold in medieval Europe, and is reserved primarily for illustrating illuminated manuscripts.

–

The rarity of blue means that people have seen it as a high-status color for thousands of years. Blue has long been associated with the Hindu god Krishna and with the Christian Virgin Mary, and artists famous for being inspired by the color blue in nature include Michelangelo, Gauguin, Picasso and Van Gogh, according to the Frontiers in Plant Science study. “The relative rarity of the blue color available in natural pigments likely fueled our fascination,” the scientists wrote.

Blue also colors our expressions, appearing in dozens of English idioms: you can do blue collar work, swear blue, drown in blue or talk until your face is blue, to name just a few. And blue can sometimes mean contradictory things depending on the idiom: “‘Blue sky ahead’ means a bright future, but ‘feeling blue’ is sad,” says Kupferschmidt.

The rarity of the color blue in nature may have helped shape our perception of the color and things that appear blue. “With blue, it’s like a whole canvas that you can still paint on,” says Kupferschmidt. “Maybe because it’s rare in nature and maybe because we associate it with things we can’t touch, like the sky and the sea, it’s something that’s very open to different associations.”

–

–