He is one of the greatest prides of American civil engineering. Straddling the Colorado River, not far from Las Vegas, the huge Hoover Dam provides electricity every day to hundreds of thousands of homes in the United States. But because of increasingly frequent droughts, Colorado could soon no longer provide enough water to power its turbines.

Millions of liters of water carried by the Colorado River pass through the turbines of the Hoover Dam near Las Vegas every day, producing electricity for hundreds of thousands of American homes.

But the chronic drought that has affected the western United States for years has reduced the volume of the reservoir so much that the hydroelectric plant may soon no longer be operational.

Twenty-third year of drought

“We are in the 23rd year of drought here in the Colorado River basin and Lake Mead has fallen to 28% of its capacity,” said Patti Aaron of the Bureau of Reclamation, the federal agency that manages the dam.

“There is no longer as much pressure to push the water through the turbines, so the efficiency drops and we are not able to produce as much energy,” she continues.

At the time of its construction, the Hoover Dam was a symbol of American ambitions and the skill of its engineers. Launched in 1931, in the midst of the economic crisis, the work had mobilized thousands of workers sweating 24 hours a day to erect what was then the largest hydroelectric dam in the world.

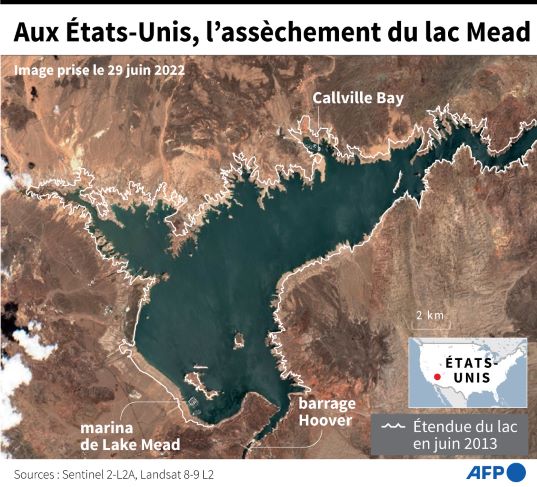

The work bars the Colorado River, giving rise to Lake Mead, which remains to this day the largest reservoir in the United States.

At its highest, the lake reached an altitude of 365 meters above sea level. But after more than twenty years of drought, it is now at 320 meters, its lowest level since filling.

Thirty centimeters lost every week

The lake is currently losing about a foot every week. If it drops below 289 meters, the dam gates will no longer be submerged and the turbines will stop.

“We are working very hard to make sure that doesn’t happen,” Ms. Aaron points out.

The Colorado River originates in the Rocky Mountains and meanders for more than 2,300 km through Colorado, Utah, Arizona, Nevada, California and then northern Mexico where it empties – more and more painfully – in the sea.

It is mainly fed by snowfall which accumulates during the winter at high altitudes, before gradually melting during the warmer months.

But under the effect of climate change, precipitation is decreasing and the snow is melting faster, depriving the river of some of its resources, which supplies water to tens of millions of people and many farms.

Efforts in vain?

Boaters on Lake Mead, many of whom hail from Las Vegas and surrounding towns, say they are doing their best to preserve the water.

They cite the succulents with which they have replaced their lawns and the great efforts made in desert cities to recycle water in homes.

“But you have farmers in California growing almonds for export,” grumbles Kameron Wells, who lives in nearby Henderson, Nevada.

In Southern California, millions of homes are now forced to limit garden watering to just one or two days a week.

But in the Nevada desert, huge mansions continue to be built at the gates of Las Vegas and green golf courses seem to emerge from the arid and dusty landscape.

Consequence of climate change

For Stephanie McAfee, a climatologist at the University of Nevada in Reno, the American West has always had this improbable side. “The average rainfall in Las Vegas is about ten centimeters a year,” she told AFP.

“For large cities like Las Vegas, Phoenix or Los Angeles to exist, we use the water that falls in the form of snow in western regions that are much wetter” and farther away, adds the scientist.

The past two decades of drought are not all that rare on a climatic scale, according to her. But “what is happening now is that we have drought and temperatures that are much warmer, and when the temperatures are high, everything dries up more quickly”.

“It is the consequence of climate change fueled by greenhouse gas emissions from human activities.”

On Lake Mead, Jason Davis, a boat salesman, maneuvers his boat in the direction of the titanic Hoover Dam, on the sides of which rings formed by mineral deposits bear witness to the level that the water reached a few years ago.

For him, the work is not so much an electricity generator as a landscape that must be protected.

“People who haven’t come can’t realize. It’s + out of sight, out of mind +. But we use too much water,” he says. “Until you see these rings, you cannot understand” the problem.

With AFP