As Xi Jinping enters his third term as president, he is making sweeping changes to the rest of the country’s leadership. And it is mainly his loyal allies who can count on promotion.

China’s Supreme Leader Xi Jinping was nominated Friday for a standard-breaking third term as state president. In doing so, he further formalizes his position as China’s most dominant leader in decades.

The announcement came as no surprise: Xi oversaw the abolition of presidential term limits in 2018 and in October secured a third term as head of the Chinese Communist Party, the position from which his real authority stems. As the annual meeting of the Chinese legislature concludes in the coming days, many of his supporters are being promoted to the country’s highest posts.

They will be tasked with reviving the economy languishing after three years of Covid restrictions, increasing security and aiming for self-sufficiency in strategic technologies. That should counterbalance what Xi has described as a campaign of “complete containment, encirclement and suppression” by the United States.

The choices are already clear for many of these positions, but there is still some uncertainty about a number of them. Below is a look at the selection.

Premier

Premier is the second most powerful position in China, and it will go to Li Qiang, who rose to No. 2 in the Chinese Communist Party last fall. As prime minister, Li becomes China’s top bureaucrat, heads the government and has significant say in economic policy.

The position has weakened under Xi, who is widely believed to have sidelined the outgoing prime minister, Li Keqiang. But some analysts say Li Qiang could play a bigger – but not necessarily more influential – role than his predecessor. Li Qiang, former secretary of the Communist Party of Shanghai, has long been an ally of Xi, and his appointment is likely due to his perceived loyalty to the top leader. Last spring, for example, he oversaw the two-month coronavirus lockdown in Shanghai as part of Xi’s zero-covid policy.

Li’s experience in leading economically important regions – in addition to Shanghai, he also held top positions in the prosperous provinces of Zhejiang and Jiangsu – has fueled hopes that he will pursue business-friendly policies. But he lacks experience in Beijing, which may make him more dependent on Xi’s continued support and less inclined to pursue policies inconsistent with the top leader’s wishes.

Li’s new position will be confirmed on Saturday and he will make his public debut as prime minister at a press conference with vetted questions at the end of the congress.

Executive Deputy Prime Minister

The executive vice premier is the highest-ranking of China’s vice premiers, the officials directly under Xi and the new prime minister. This post is expected to go to Ding Xuexiang, who has served as Xi’s secretary and chief of staff in recent years.

In this position, Ding will likely also be responsible for day-to-day economic policy. Outgoing Deputy Prime Minister Han Zheng was a former Communist Party secretary of Shanghai who spearheaded its transformation into a cosmopolitan financial capital. Ding, on the other hand, never ran a province and worked mainly as a behind-the-scenes technocrat.

But like others up for promotion, Ding has long-standing ties with Xi. He is widely believed to be the director of China’s National Security Commission. That secretive body has gained influence as Xi has emphasized the need for vigilance against foreign and domestic threats. Ding has also traveled frequently with Xi, both domestically and overseas.

Han, the current vice premier, has been named vice president of China. That is a largely ceremonial role.

Head of the Chinese legislature

Zhao Leji, named No. 3 in the party hierarchy last fall, was approved as head of the National People’s Congress. That is the Chinese legislature.

The legislature officially has the power to make laws and change the constitution, but in reality the decisions are made by top party officials. Zhao has kept a relatively low profile, but his responsibilities have been significant in recent years. For example, he headed the party’s Disciplinary Inspection Committee, which is charged with carrying out Xi’s campaign against corruption and disloyalty among officials.

That campaign has been key to Xi’s consolidation of power and purge of rivals. Before taking on the disciplinary task in 2017, Zhao was a top official in charge of party human resources, which gives him extensive experience in internal affairs.

Head of the political advisory body

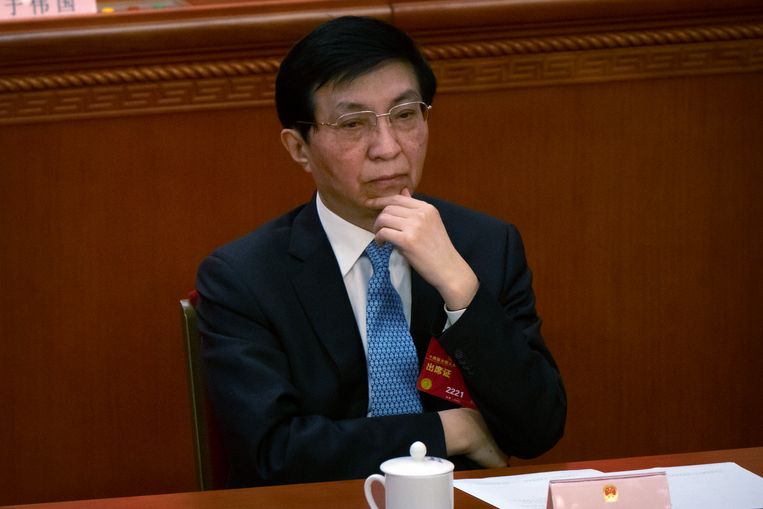

Another group also meets in Beijing at the same time as the annual legislative session, which acts as a political advisory group to the government. This group, called the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference, is likely to be headed by Communist Party No. 4 Wang Huning.

In this position, Wang will oversee approximately 2,000 representatives who ostensibly make political and social policy proposals; in reality the conference works more like one soft power for the party, which mobilizes resources and non-party members from across Chinese society to support the party’s agenda.

Wang is known as the party’s main ideologue: he has served three successive leaders in making propaganda and writing speeches and policies. He helped shape Xi’s motto of the “Chinese Dream” – a vision of national rejuvenation under Xi’s leadership – and his political rise signals the continuation of the party’s hardline, anti-Western policies.

Economic chief

He Lifeng, another former loyal aide to Xi, will work closely with Li to revive China’s economy. He, who is expected to become deputy prime minister and oversee economic and industrial policy, currently heads China’s National Development and Reform Commission, the country’s economic policy planning committee. In that role, he has overseen the preparation of China’s five-year plans and major investment projects at home and abroad.

Compared to outgoing economic chief Liu He – a Harvard-educated economist who also led trade talks with Washington – he has little foreign experience. He worked for 25 years in southeastern China’s Fujian province, where he also occasionally worked with Xi as he rose in rank there, and then became deputy secretary of the Communist Party in the megacity of Tianjin.

His close ties to Xi suggest he will play a key role in implementing the leader’s vision of a security-oriented, state-led society. In this, economic growth comes in second place, after ideology.

© The New York Times