Helmut Kettenmann, neuroscientist at the Max Delbrück Center for Molecular Medicine in the Helmholtz Association, translated into German and English for the first time the dissertation that Hermann Helmholtz submitted in Latin in 1842 at the age of 21 at the Friedrich Wilhelm University in Berlin, introduced and commented, together with the classical philologist Julia Heideklang from the Humboldt University and the neurobiologist Joachim Pflüger at the Free University of Berlin. It has been available in bookshops since August.

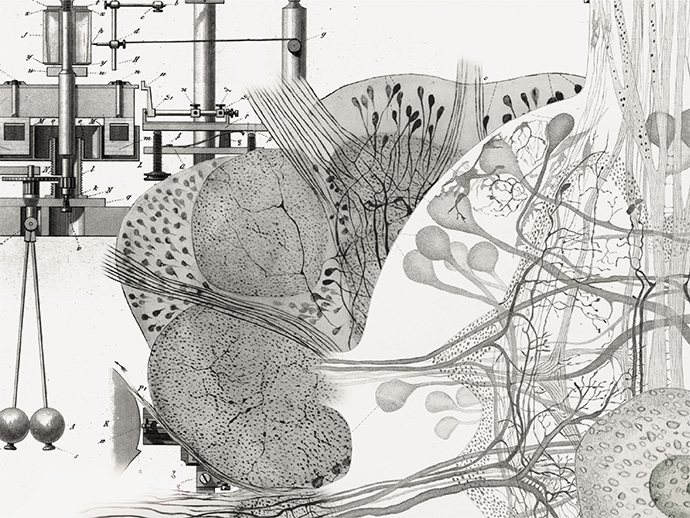

Helmholtz examined the nervous systems of insects, spiders, crabs, snails and worms and compared their external structures as well as the internal fine structure. He described nerve cells with their fibers and recognized the general structure of ganglia of the abdominal cord. He recognized many similarities in the central nervous systems of invertebrates and vertebrates.

How and why did you come up with the idea of translating an almost 170 years of doctoral thesis from Latin?

It was rather by chance that I found out that Helmholtz had published something in the field of neuroscience, in Latin. I wanted to know more about it and found that this thesis was never translated into any other language. My Latinum was 45 years ago and a computer translation was of no use. I contacted the Helmholtz Association and suggested that this text absolutely had to be translated. I received financial support and in Julia Heideklang I was able to win a classical philologist who mainly deals with Latin scientific texts from this period. Joachim Pflüger works on the nervous system of invertebrates, while I am a vertebrate specialist.

How did you proceed?

Julia Heideklang first translated close to the text. Together we then worked hard to translate the text into a language that a scientist can understand. The terms from then are no longer the ones we use today. The term neuron, for example, wasn’t coined until 50 years later.

How long did it take from the idea to the finished book?

I sent the application to the Helmholtz Association in November 2020 and the book has been available since August 1st.

Why has the dissertation never been translated before?

Back then, all dissertations were published in Latin. This regulation was only relaxed in the 1860s, so that dissertations could also be published in German. Nobody came up with the idea of translating Helmholtz’s work retrospectively.

Was it worth? Did Helmholtz write anything relevant?

He really wrote a fundamental piece of work, it’s unbelievable what kind of insights he had at the time and what insights he came to. It is hard to believe that this work has slumbered for so long.

What does his dissertation tell us today?

You have to go back in time. At that time, neuroscience was a very young discipline. The cell theory had only emerged four or five years earlier. Henle and Schleiden formulated it in 1838. It says that all tissues are made up of individual cells. A fundamental finding. And that gave rise to the question: How are nervous systems structured? The first picture of a nerve cell was only published in 1836, only six years earlier. Then of course there was an exciting question: We humans use the brain to recognize ourselves, we can well imagine that a dog or a cat could react in a similar way. But if we look at a leech or an earthworm, does it even have a nervous system? Does he need one? How does it look? Helmholtz’s doctoral thesis examined a number of invertebrate species: earthworms, crayfish, mussels … and he analyzed these nervous systems on a microscopic level.

With what result?

That the nervous systems of all these invertebrates are basically identical to that of vertebrates through to humans. They consist of nerve cells, of nerve fibers that are connected to one another, and nerve centers, in invertebrates it is ganglia, i.e. clusters of nerve cells. With us it is very centered in the brain, but it also goes into the spinal cord, there are also peripheral ganglia that control our bowel movements, for example. If you compare all of this, the general blueprint of nervous systems is identical throughout the animal kingdom. He formulated this thesis in his doctoral thesis. That is the essence. He was the first to systematically analyze nervous systems in the animal kingdom on a microscopic level.

The translation does not only live from the sound of the name Helmholtz and from the fact that the community’s employees can put it on their shelves. Is that where researchers can find insights and suggestions even today?

In fact, I think it should be required reading for neuroscience students.

Was Helmholtz’s achievement really that extraordinary for the time?

You can really say that. He brought forward a vision that wasn’t there before. Or not formulated with this clarity. The work, for example, has implications that continue to this day.

Namely?

Especially in the 1960s and 1970s, when I started out in neuroscience, it was common practice to use invertebrate systems as model systems to explain fundamental principles in neuroscience. Because all the paradigms of how memories are stored are similar from snails to humans. All of these fundamental mechanisms can be researched in invertebrates because the basic structure of their nervous system, the entire molecular structure, the entire molecular mechanism, is identical to that of vertebrates like us humans. I worked on the crayfish walking process when I was a student and the fundamental mechanisms are the same. These foundations for the fact that invertebrate systems can be used as models for human nervous systems actually come from the Helmholtz work.

Did the translation run more smoothly after a certain amount of familiarization?

Well, let’s put it this way: It was a challenge. Just finding out what he meant when describing things in his words. To do this, you have to be familiar with the system that he saw. That’s why I brought Joachim Pflüger on board, who is very familiar with the invertebrate nervous system. If you don’t know that and someone describes it in flowery words, then you don’t know what Helmholtz meant. Unfortunately, he didn’t have enough money to illustrate his work. Back then, that was only possible with expensive copperplate engravings.

What do we know about the reception of the original work written in Latin? Has she been quoted a lot?

As a rule, the doctoral theses of the time were all rarely cited. The close circle knew that, of course. The well-known physiologist and anatomist Johannes Müller, for example, gathered all the students at this Berlin school, including Rudolph Virchow, who defined cell pathology, and Emil duBois-Reymond, who measured the electrical activity of the nervous system. The basics of neuroscience, the first image of the neuron, all of that was created during this time. In Berlin. They all knew each other, of course. They read it in Latin, but it has been lost for the next generation. An aspect that is still important from this time: That was the first time microscopy was systematically introduced into both research and teaching. Berlin was the center for this. At the same time, an entire industry that built microscopes has emerged.

One could assume that there are still some interesting works dormant from that time.

One can guess, yes.

In this case, the advantage of the prominent name helped to bring one of them out of oblivion.

Right. Otherwise I would never have looked at it.

Interview: Thomas Röbke

The publication:

Heideklang, Julia / Pflüger, Hans-Joachim / Kettenmann, Helmut: De fabrica systematis nervosi evertebratorum. The annotated dissertation of / commented thesis by Hermann Helmholtz, 2021, wbg Academic.

23. August 2021

–