Today the postcard appears to us as a rather trivial object; even as a holiday greeting, it has long since been replaced by email messages, Instagram or Facebook. But in the late nineteenth century it was an exciting invention. Writers, philosophers and visual artists grappled with it, while politicians pondered the dangers of this new medium. Picture postcards in particular exerted a great attraction.

Inspired by the gallery owner Rose Schapire, Karl Schmidt-Rotluff and other painters from the artist group “Brücke” in Germany sketched their works on blank postcards and circulated them among themselves. Else Lasker-Schüler and Franz Marc maintained a correspondence that was supported by self-painted postcards, some of which in turn were included in Lasker-Schüler’s book publications. Franz Kafka liked to write postcards, and wrote and drew in the ready-made images.

As a child, Walter Benjamin received a postcard collection from his grandmother and continued to collect; he bought postcards in Paris, as when traveling, which were intended to inspire him to write texts such as his cityscapes and his arcades. Alfred Döblin’s postcard albums, which show, among other things, Berlin around Alexanderplatz, the geographic center of one of his novels, have survived to this day. One would have to write a philosophy of the postcard, Benjamin remarked in a letter to Siegfried Kracauer. In turn, he photographed Paris with his wife Lili – in postcard format. But what should a philosophy that adheres to this small object look like?

A German-Austrian story

The postcard only became possible in 1840 with the invention of the first penny stamp in England, because with it the postage was not paid after receipt of the letter and measured by its distance, but according to its weight and in advance. When the Prussian postal officer Heinrich von Stephan suggested to the North German Post Federation 25 years later that a simple “Postblatt” be introduced for carriage, he cited many reasons in favor of introducing such an innovation. A postal sheet was light and therefore economical, and letter writing would be accelerated.

The emphasis on the speed of writing, sorting and delivering a letter touched on an important point at the time of the industrial revolution and technological advances, speed was required. However, von Stephan also hoped that the limited writing space would encourage a more focused style of writing. The Postblatt was also to establish itself as a cheaper and therefore more democratic competitor to the telegraph. For von Stephan, the Postblatt was the last link in a series of writing techniques that began with the ancient wax tablets. For him, the concrete model for the Postblatt could be found in banking; so he compared it to the semblance of money transfer that had been in use for some time.

Unfortunately, von Stephan’s suggestion was unsuccessful. His promised letter transfer did not seem to be economically profitable. However, the government was also concerned about maintaining the secrecy of letters and protecting the privacy of correspondents; without a protective envelope, unauthorized readers could view the messages sent. However, just four years after the German application was rejected, the Austro-Hungarian Post tried and was successful with their application. In 1869, Austria became the first country to approve a “post sheet”, now known as a “correspondence card”, for official correspondence. This time, however, it was not a postal clerk but an economist, Emmanuel Hermann, who was able to present the correct calculations, and Hermann was henceforth celebrated as the inventor of the postcard.

The postcard was thus considered an Austrian innovation. But the German postal system quickly followed. Von Stephan was promoted to general post director of the North German Confederation of States, paving the way for the victory of the postcard. In July 1870 the postcard was officially introduced in northern Germany. The rules of postcard writing have been clearly identified. On the front it should show the stamp and the recipient’s address; the back was reserved for the message. The sender’s address should not be noted. The content of the card was intended to reflect the morality of the time; Recipients and postal workers needed legal protection. So soon six precise instructions for writing postcards were printed on the back of the card and thus came under every message.

Between War and Tourism

The war between France and Prussia in 1870-71 helped increase the popularity of the postcard, which was invented just before the war broke out. The weight of the letters became particularly relevant for sending mail during the war. France experimented with sending mail using hot air balloons. The first picture postcard appeared as a French field postcard during the war. However, private companies soon began to produce correspondence cards as well and to decorate them with pictures, which soon surpassed the first field postcard in terms of visual appeal.

Field postcards became a genre of their own in later years. During World War I, for example, soldiers could give friends and family a quick message of their well-being by simply ticking off pre-printed sentences. What was initially seen as a disadvantage of the postcard – its obvious legibility – accommodated the war censorship. This is how it happened that Franz Rosenzweig wrote his main philosophical work, the “Star of Redemption”, as a soldier in the Balkans on field postcards and sent this special series of manuscripts home in this way.

But by that time the postcard had already changed. After 1905, when the address page was divided, full-page images could also be reproduced, and new printing technologies made it possible to reproduce photographs. This imagery recommended the postcards for the new tourists of the turn of the century, but also for collectors and collectors in particular. Because while men began to collect stamps, the field of postcards was particularly open to women. You could put them in albums, but women’s magazines also offered instructions for decorating wallpaper or furniture with picture cards.

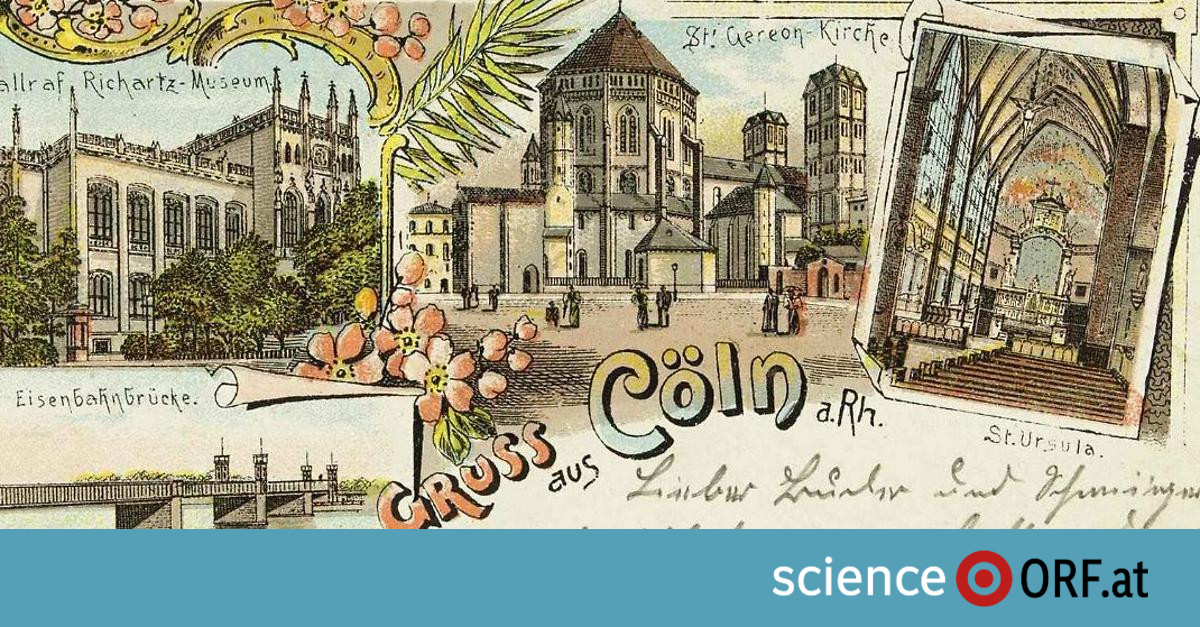

Many of these new picture cards showed views of towns and localities, followed by advertising and greeting cards. The address side was still distinguished from the news side with these, and the news had to share the space with the image. The text was written by hand below or to the side of the lithographed image, the text and image should be seen and read together. New printing technologies made this possible.

The golden age of the postcard

The golden age of the postcard is now often placed between the late nineteenth century and the late 1920s. For Germany, however, the period between the Franco-Prussian War and the First World War was particularly important. In 1871, after the victory of Prussia, the German Empire was formed and the postcard now supported the national German project. The places of the new empire and its capital were made known with the help of picture postcards.

In the process, German publishers and printers became the main producers of postcards. The old centers of book production, above all Leipzig, became centers of postcard printing. German companies exported postcards to all European countries and also to the United States. Between 1895 and 1920, around 200 billion postcards were circulated around the world. The most eager postcard writers also came from Germany. German dominance of the postcard market as producer and consumer ended with World War I, another war that curtailed mail and all tourism, and it was Germany’s defeat that ended the monopoly of German publishers. And the golden age of the postcard was also over a few years later.