Born in Barcelona in 1923, it goes without saying that Antoni Tàpies was one of our fundamental painters of the second half of the 20th century. By generation he had to live, right at the beginning of his adolescence, the Civil War and then the postwar period, with the consequent isolation of Spain in the artistic and cultural field until at least 1950, which would constitute a serious limitation in his projection. Despite these circumstances, and also overcoming a delicate health (he overcame a lung disease that kept him prostrate in 1942 and 1943), he managed to assert himself in his creative vocation and, after abandoning his training in Law, he oriented himself along the paths of law. Vanguard.

Thus, delving into his own concerns and also rummaging through books and magazines, the Catalan connected with other young people with similar inclinations and founded with them the Dau al Set collective, one of the first platforms for artistic renewal in postwar Spain, when it became partially in reflection of the cosmopolitan desire in our country and also to recover immediate historical memory. The issues published by the group’s trilingual magazine offer in this regard very valuable material: among its collaborators were Arnau Puig, Joan Brossa, Tharrats, Juan Eduardo Cirlot, Santos Torroella, Gaya Nuño, Antonio Saura, Ricardo Gullón …

In his autobiography Personal memory, Tàpies remembers those early years from his own gaze as a young painter who tries to carve out an intellectual training and connected with groups that were gradually developing, such as The Eight, with whom he exhibited at the Blaus de Sarriá, and with the collaborators of the magazine Ariel. In addition, he rediscovered the great figures of the historical avant-garde, such as Picasso or Miró, who were then viewed with suspicion by the official authorities, and also related to Joan Brossa, Josep Vicenç Foix or Joan Prats.

Strictly pictorial, he showed his fascination for Paul Klee, Miró, Kurt Schwitters, Duchamp…; in his words, All of this was like a stream of new ideas that were set in motion within me, albeit with a long delay, due to the years of closure in our country. If we had lived in a normal situation, perhaps I would have assimilated them earlier and with more positive results.. Like other young artists of his time, he intuitively sought a way out in the recovery of the censored and in an accentuated search for cosmopolitanism. Similar motivations can be found at the end of the 1940s in the Pórtico Group in Zaragoza or the Altamira School in Santander and that was also the moment when Eusebio Sempere, Manolo Millares or Saura started.

Although its early production, the one dating from the second half of the 1940s and early 1950s, reflects the circumstances of that period in Spain, it cannot be circumscribed in any way to our country. Tàpies’ stay in Paris in 1950, from which he began to relate to Gallic informalism and the international avant-garde, was essential in the maturation of his language and in the expansion of his aesthetic horizons; In 1953 he completely abandoned the magical-surrealizing figuration and, since then, began a personal career that soon made him one of the most relevant authors of the second half of the century.

In this sense, he soon surpassed the postulates of French abstraction, showing different concerns; More relevant for him was the influence of the French critic and intellectual Michel Tapié, author of the fundamental essay One art another (1952); In addition, existentialist philosophy and his fascination for oriental culture and thought had an impact on the configuration of his own artistic world. By the mid-fifties, the painter had already opted for a very personal use of the subject.

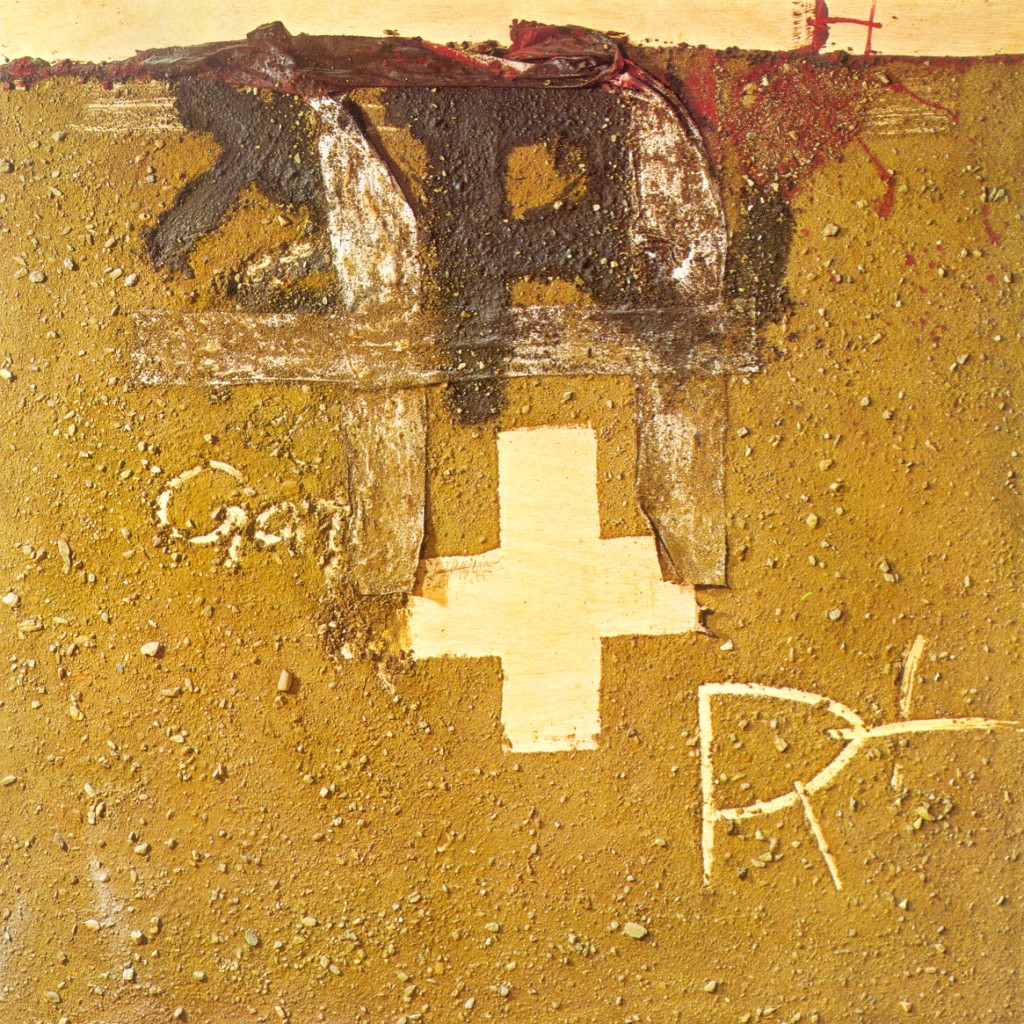

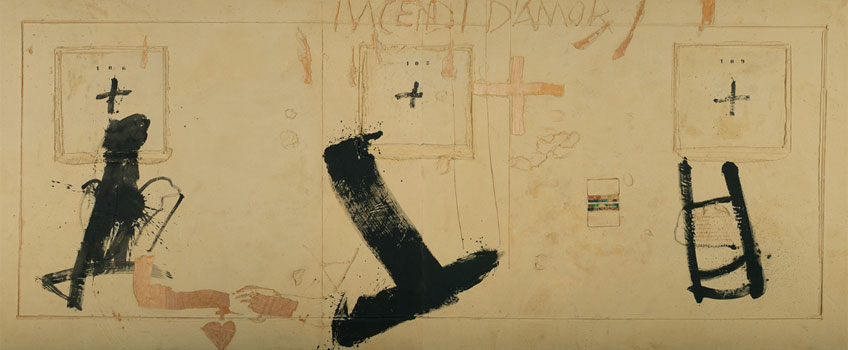

His style would mature from then on precisely in the coordinates of material informalism, which would lead him to experiment with sand, marble dust, resins or colored earth. On that physical support, he simultaneously distilled his program of signs, which includes not only some of great symbolic significance (the cross, which coincides and is identified with the first letter of his surname), but also a personal way of influencing the matter. Comparing these signs or traces with his previous figurative repertoire, an austerity, an economy of means, more interesting and effective, can be appreciated.

Analyzing their style over time, these works show a surprising complexity and richness, as they refer to the best of the pictorial tradition of our country (to the sensitivity of the mystics of the 16th century), but also to contemporary avant-garde art, since They interested Tàpies more common than informalism and abstract expressionism: their images indicate an assimilation of spatialism, the art of assemblage and other paths frequented by Dadaism. For the rest, the wealth of record that Catalan shows in the fifties grew and became more complex in the following years, when he also cultivated his harmony with arte povera and Joseph Beuys and experimented with abundance with the three dimensions.

During the 1980s, he returned to the plane but did it, again, with originality, using large formats, a virtuous use of varnishes and some figurative elements with erotic echoes.

Active until his death, it is difficult to summarize his artistic contributions. Educated, refined and committed, he is the author of several books, such as Artistic practice (1970), L´art against l´estètica (1974) o Reality as art (1989). As a creator, he also illustrated poetic texts by great Spanish and foreign writers.

In 1990 he inaugurated the Foundation that bears his name in Barcelona, whose collection is nurtured by works that were his personal funds and also by his library, full of art books and a careful selection of publications on oriental culture.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=plirhuiQmho

–

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Juan Pablo Fusi, Francisco Calvo Serraller. The mirror of time. The history and art of Spain. Taurus, 2012

–