When I think about the most important directors in the history of cinema, the fact that all their works are united by several common features, both plot-wise and also visually, seems only a logical proof of mastery. As it often turns out, looking back at the director’s work many years after the author’s death, even works that were not understood at the time often acquire new meaning and value, because, being in a distant perspective in terms of years, we are able to watch the film without the prejudices that the viewer who saw the film may have had seen immediately after its premiere. But recently, people on the Internet especially like to “bind” the principle of “one cinema universe” as a big discovery to those few living authors who continue to create only big films.

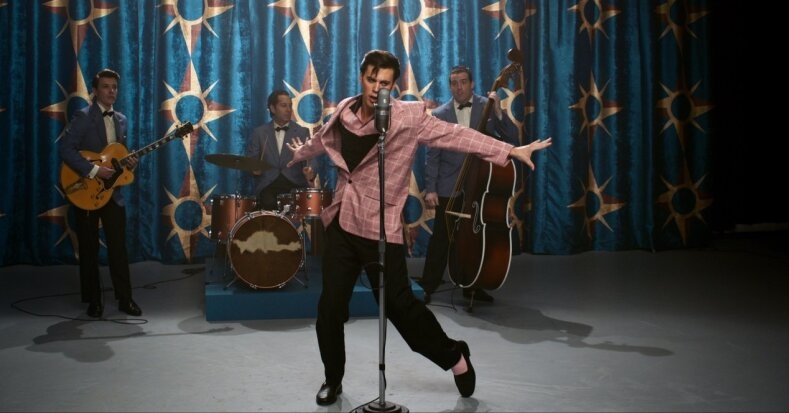

Quentin Tarantino, without any other common denominator, puts the same self-invented products into his feature films. There is no doubt that all the characters of Wes Anderson, even Lars von Trier, Michael Haneke, and certainly Leo Carax, Jean-Pierre Genet and Harmonie Korin live in the same closed world created by the director. Perhaps Australia’s most important director Baz Luhrmann’s best films so far have been united by a single dreamlike aesthetic – we were watching something well-known, but what we rarely saw resembled anything we had imagined about it (and, as in a dream, anything could happen). But suddenly, instead of a kitschy dream, we have a biographical piece in front of us – the creative process of rock and roll king Elvis Presley and the history of his relationship with manager Colonel Parker in the two-and-a-half-hour long musical film “Elvis”.

The plot

There are cases when it is useful for any viewer to inquire in advance about the roots of the upcoming art experience. If this is not done, the reaction of the public can be quite amusing. It’s really hard to imagine which ones

–