Imagine being able to be chopped into small pieces and then come back in good shape after about two weeks. Or if the heart could form new, healthy heart muscle cells after a severe heart attack.

The ability to recover lost body parts and dead tissue is not entirely uncommon in the animal kingdom, although the centimeter-long vortex mask Mediterranean Schmidtea, which can withstand a total chopping, belongs to the extreme cases. Slightly less spectacular but from a human perspective still dizzying varieties are, for example, zebrafish, salamanders, certain lizards, lobsters, crabs and starfish. The salamander and zebrafish, for example, can repeatedly get rid of large parts of the eyes, brain and heart without the damage becoming permanent.

It is not clear whether the ability to regenerate body parts is original and is dormant to a lesser or greater extent in most organisms, or whether it has appeared a little here and there through evolution.

–

–

With us humans and the other mammals it is in any case only in a very modest format. When we get a serious injury, the body’s cells usually form a rigid scar tissue instead of regenerating the parts that have been lost, so-called regeneration.

– We still have a certain ability as children. Until we are maybe seven or eight years old, our fingertips can, for example, grow back if they are damaged or cut off completely. But as adults, we can no longer fully recreate any tissue, says Nirosha Murugan, a researcher in regenerative medicine at Algoma University in Canada.

Like many other researchers studying regeneration, however, she believes that it should be possible to induce this type of process even in species that do not have it in them naturally, if one only manages to figure out which signals control the cells’ behavior after an injury.

The haunting goal is man. On the wish list are things like getting the brain to form new nerve cells in Parkinson’s disease, for example, that the heart could exchange the scar tissue for healthy heart muscle cells after a heart attack – or at least that large wounds can heal without scars.

– We are absolutely approaching that opportunity. But when it can be possible, how long it can take before we are there, I can not answer that, says Nirosha Murugan.

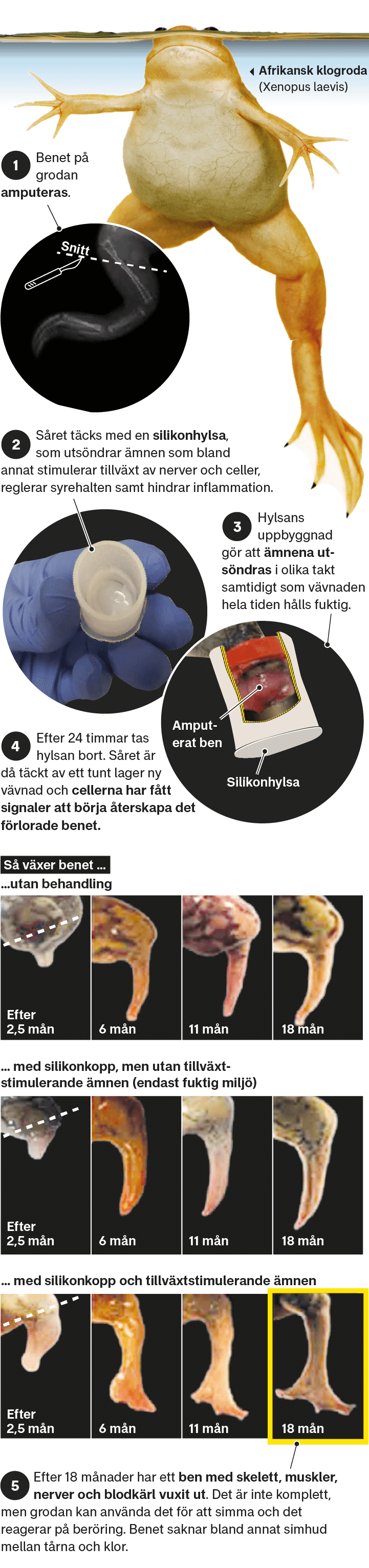

She recently presented together with their research colleagues a discovery that can provide important pieces of the puzzle. The research group has studied African claw frogs. It is a species that can regenerate, for example, a lost bone until they become sexually mature and move up on land. Then the ability disappears.

But in a study that has now been published in the journal Science Advances The researchers show that if the wound after the lost bone is treated correctly, then even adult frogs can form a new and fairly complete bone.

This is how a frog gets a new leg

African claw frog can recreate certain body parts as a fry, but not as an adult. In a new study, American researchers have succeeded in directing the cells of an adult frog to recreate an amputated hind leg.

Graphics: Johan Andersson Facts: Jörn Spolander Photo: Alamy Sources: Murugan et al, Science Advances (2022)

–

–

The trick is, explains Nirosha Murugan, to keep the wound moist for the first 24 hours with the help of a kind of silicone sleeve that is threaded over the stump, and which also secretes a mixture of different substances that stimulate the growth of nerves and cells, prevent inflammation and help the cells to regulate the oxygen content.

– The first 24 hours after an injury is a very critical period. This is the time when cells are most susceptible to chemical signals. Then it is important to insert the right type of signals that the cells can respond to, so that they are directed towards regeneration instead of scarring, says Nirosha Murugan.

After 24 hours, the silicone sleeve was removed. By then, a thin tissue had formed that protected against infections, so that the bone stump could continue to heal and grow on its own for about 18 months.

Nirosha Murugan emphasizes that it was not a perfect hind leg that grew out of the frogs in the treatment group. For example, claws and swimming skin were missing between the toes. But compared to the control groups who either only had a silicone sleeve without active substances, or did not receive any treatment at all, it was a much more functional and useful body part.

The new bone worked so that the frogs could swim normally, and it also reacted to touch, which shows that nerve connections had formed in the tissue.

– The fascinating thing is that complex structures were formed that are found in normal bones. Skeletons and connections between nerves and muscles were recreated in a way that is otherwise not possible at all in adult frogs, says Nirosha Murugan.

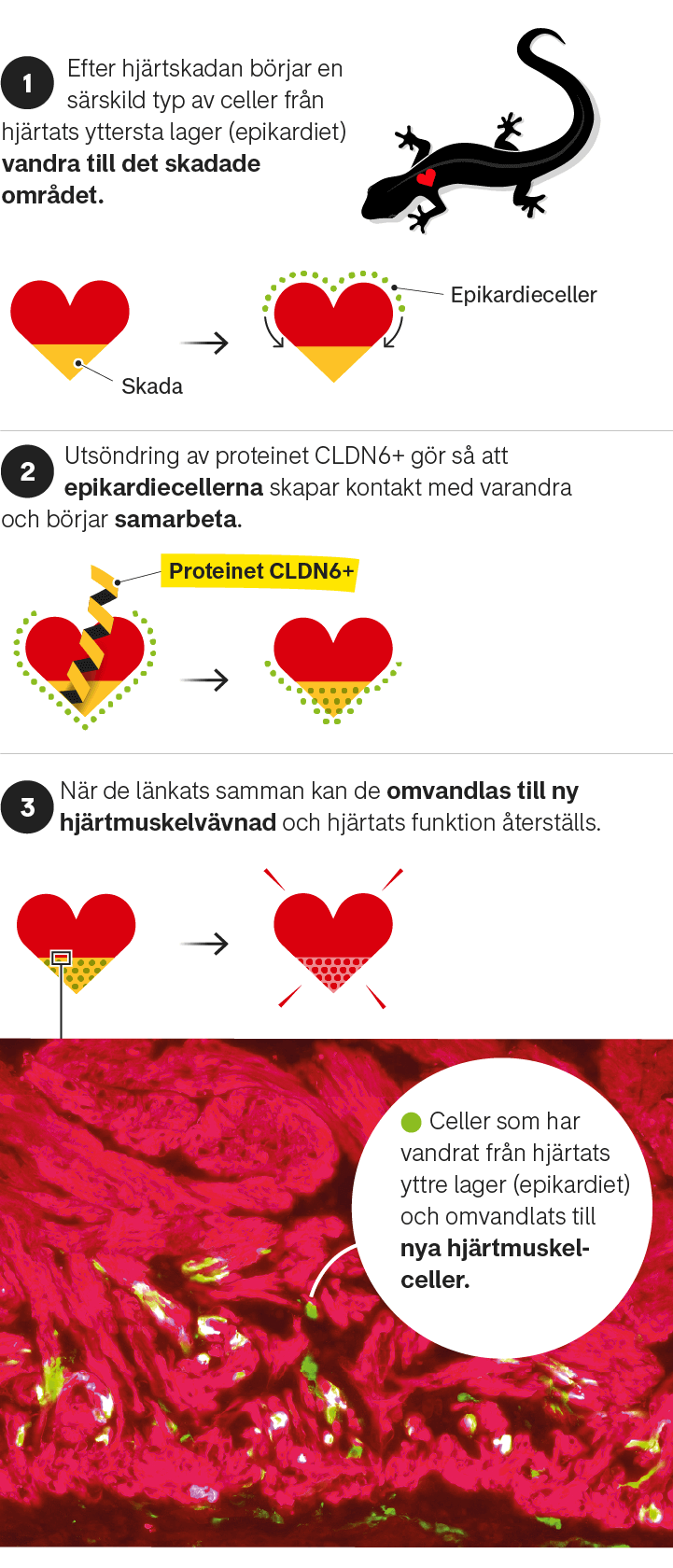

The cells that repair the salamander’s heart

Salamanders can also, as adults, recreate almost all parts of the body, such as bones, arms and parts of the eyes and brain – as well as the heart. A new study by researchers at Karolinska Institutet shows how it goes when the salamander recovers heart muscle cells after extensive damage:

Graphics: Johan Andersson Facts: Jörn Spolander Sources: Eroglu et al, Nature Cell Biology (2022)

–

–

Another recent breakthrough in regeneration research has been done at Karolinska Institutet in Stockholm. There, Elif Eroglu, a researcher at the Department of Cell and Molecular Biology, together with, among others, Professor András Simon, discovered an important mechanism that enables the Spanish rib salamander to repair its heart after losing as much as 25 percent of its heart muscle cells. It turned out to be an interesting parallel to man.

Unlike the claw frog, the rib salamander has an outstanding ability to recreate body parts even as an adult. But exactly how it goes is still largely shrouded in obscurity.

In the new study, published in Nature Cell Biology, the researchers show that there is a supply of cells in the outer layers of the heart that begin to move inward after a heart injury. There, they connect with each other and are transformed into new heart muscle cells.

– The interesting thing is that this is not a unique type of cell that is only found in salamanders. They are also found in mammals and us humans, says Elif Eroglu.

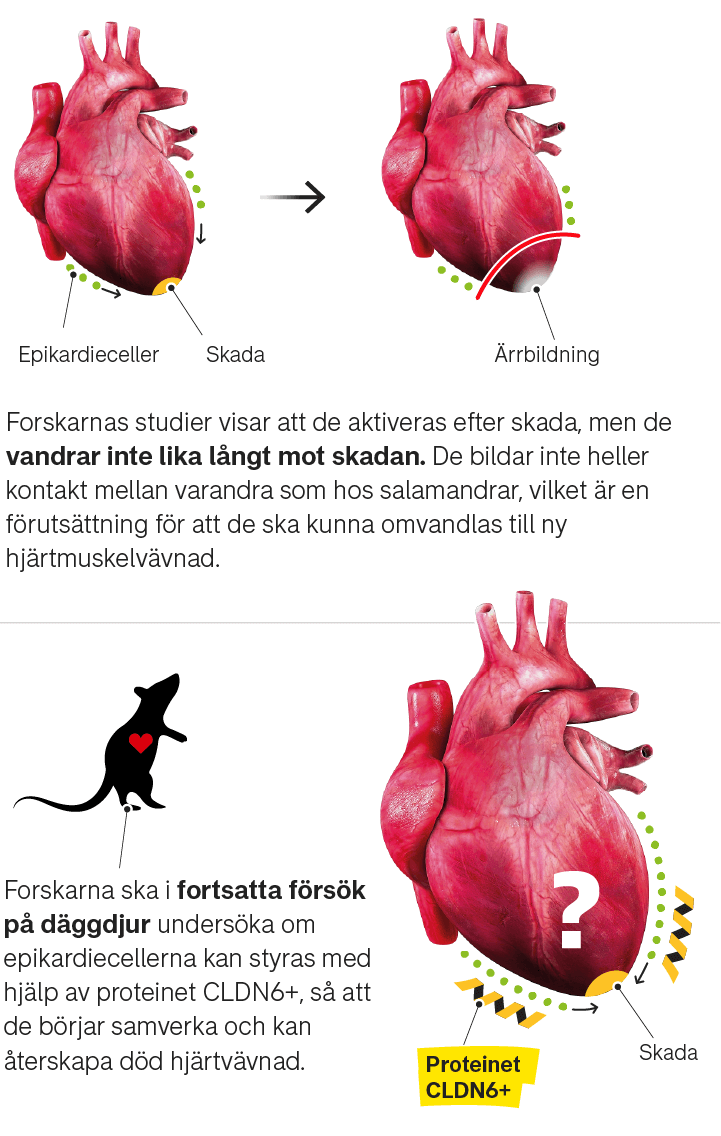

The same type of cells are found in the human heart

Mammals, like us humans, have the same type of cells in the epicardium of the heart.

Graphics: Johan Andersson Facts: Jörn Spolander Sources: Eroglu et al, Nature Cell Biology (2022)

–

–

But in mammals, these cells do not move as far towards the injury, and they do not manage to coordinate as in the salamander. Elif Eroglu explains that the difference seems to be due to a special protein, CLDN6 +, which helps the salamander cells to make contact with each other. This protein signal is missing in mammals – and when the researchers blocked it in salamanders, the cells could no longer connect with each other and form new heart muscle cells.

– We believe that it is a decisive factor whether the cells are alone or in a group, which controls how they feel about their surroundings, which in turn determines what they develop into, says Elif Eroglu.

“It could be a way to activate these cells in humans and get them to behave in a salamander way,” she adds.

Both research groups have now begun studies on mammals.