Three instruments from the Solar Orbiter spacecraft, including the Imperial magnetometer, have released their first data.

The European Space Agency’s (Solar Orbiter) spacecraft was launched in February 2020 with the aim of exploring the sun and starting to collect scientific data in June. Now three out of ten instruments have released their first level data, which reveals the position of the sun in a “calm” phase.

Solar orbiters do exactly what lead says. We always knew this was going to be a tremendous task, and the first measurements showed how much of this unprecedented insight into the sun was possible. Profesor Tim Horbury

The sun has been known to follow sunspot activity for 11 years, and currently gets absolutely no sunlight. This is expected to change as sunspot activity increases in the coming years, making the Sun more active and increasing the likelihood of adverse space weather events, in which the Sun emits large amounts of matter and energy in solar flares and releases coronal mass.

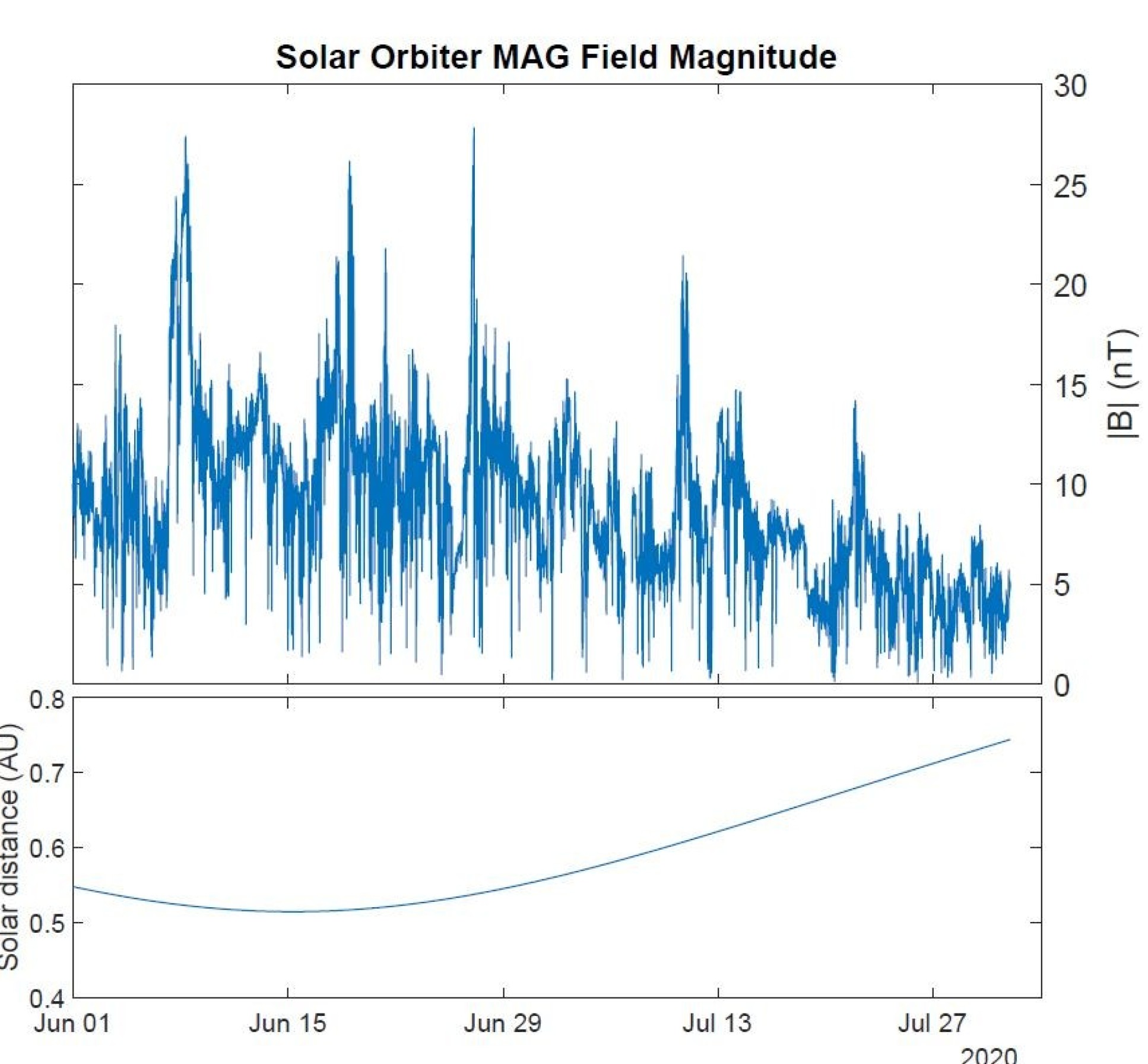

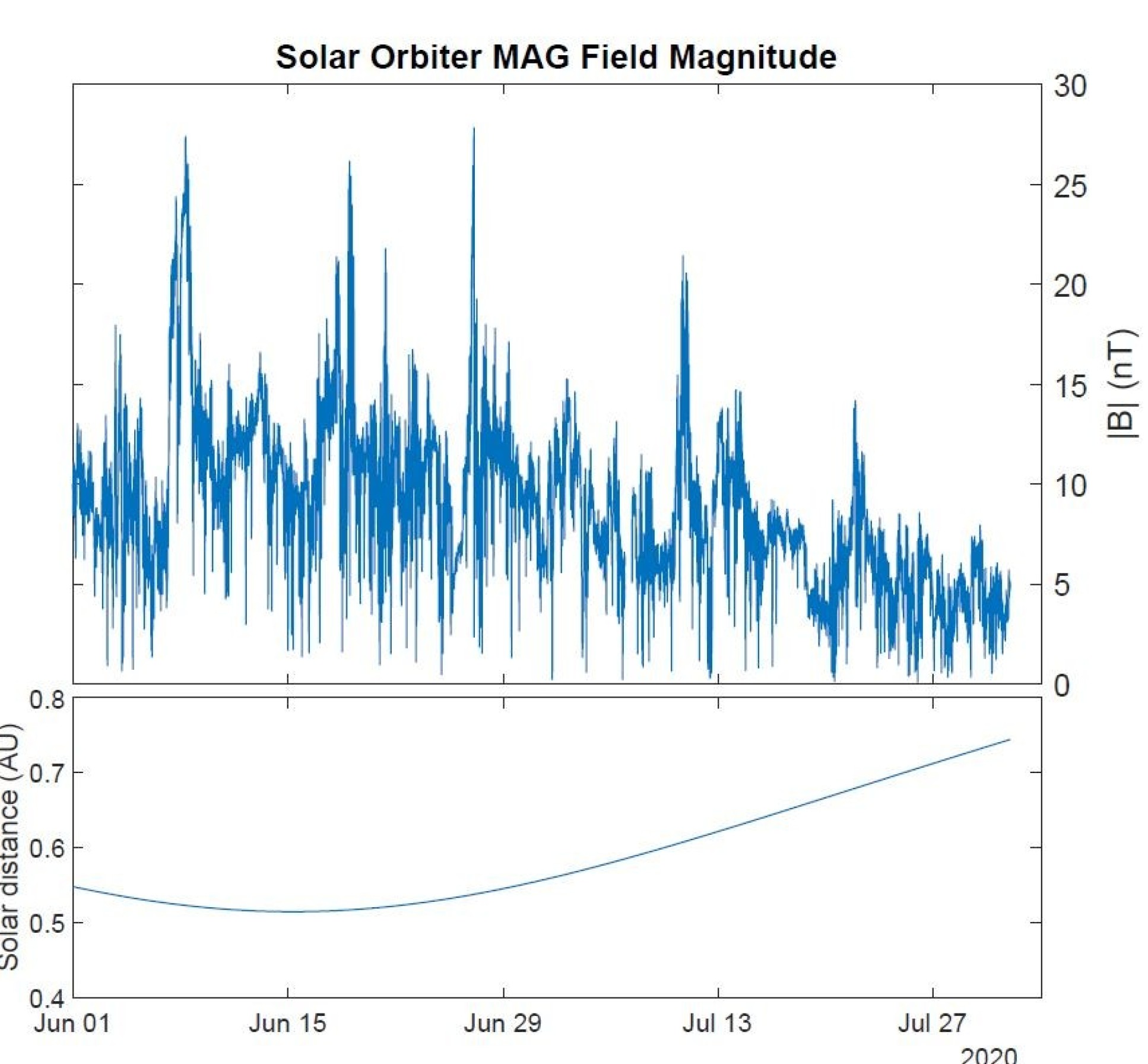

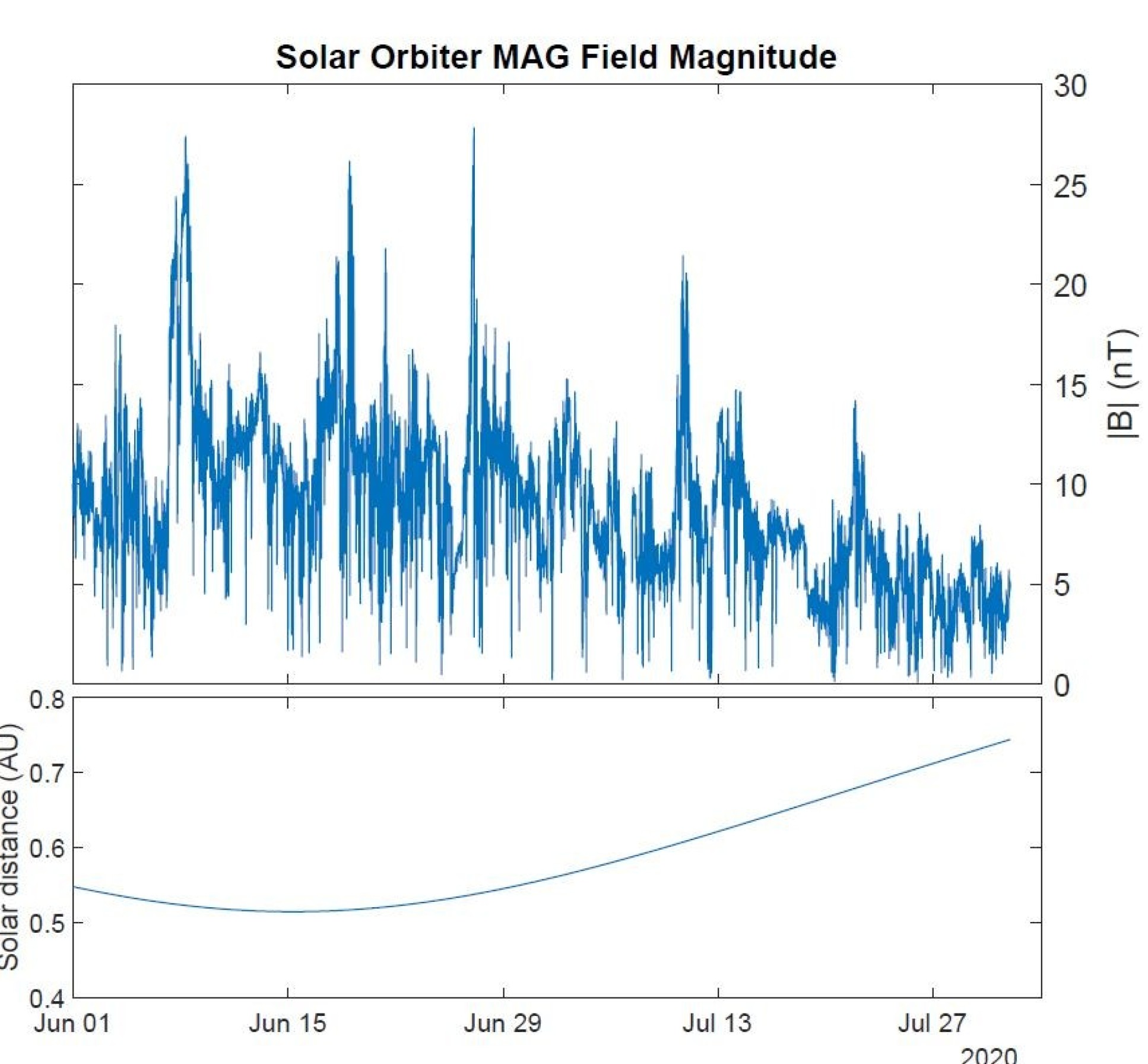

Solar activity is closely related to the position of its magnetic field and is measured using the imperial instrument on the solar orbiter, the magnetometer (MAG). Since June, MAG has recorded hundreds of millions of “vectors” – measurements of the direction and strength of the Sun’s magnetic field.

The sun’s orbit will fly into the orbit of Venus, gather some data that is very close to the sun, and will continue to approach in the coming years. It is currently orbiting near the Sun’s equator, which has a more curved magnetic field during periods of high activity.

Today, however, the Sun’s magnetic “equator” is much flatter than the true equator, allowing the spacecraft to observe the field for several weeks from the northern magnetic hemisphere just a few degrees north of the equator. During high solar activity, when the Sun’s magnetic equator becomes increasingly distorted, the polarity of the magnetic field cannot be detected at that time.

Solar wind structure

MAG also observes waves caused by protons and electrons flowing from the sun. Closer to Earth, these particles are more evenly distributed in the sun’s air than charged particles flowing from the sun, but the sun’s orbits contain “rays” of protons and electrons emanating from the sun.

There appears to be more structure in the solar wind closer to the sun, and this was further confirmed by MAG, which confirmed the existence of “snakes” – the dramatic folds in the solar wind first mentioned by NASA’s Parker Solar Probe. -mission launched.

The Solar Orbiter and Parker Solar Probe enter the next phase of the sunspot cycle when they compare data about the same event at different distances and orbits around the Sun in coming years.

Evidence of hard work

The data released today is part of the Solar Orbiter’s commitment to release data within three months of landing – a tight schedule for any space mission, but especially challenging during an epidemic. Professor Tim Horbury, Principal MAG Investigator in the Department of Physics at Imperial, said the timely availability of the data was testament to the hard work of the engineering team at Imperial.

“You have worked really hard over the last few months. It’s hard work, ”he said. But it paid off. “We published many articles that were not viewed in detail by anyone. So I hope there will be more miracles – we still don’t know what they are. There are a lot of things to do, I hope people will come. “

MAG has shown excellent performance for seven months. We tested this on Earth before launch, but we weren’t able to completely create a harsh space environment, certainly not long enough to experience MAG. Helen O’Brien

One of the team’s first challenges was to remove tiny magnetic field marks from the spacecraft itself. Almost all spacecraft that use electrical energy produce a different magnetic field, which must be extracted from the data to receive a real signal from the sun. This includes solar panels, plungers, other scientific instruments and more than 50 individual heaters.

When starting different parts of the spacecraft, the crew must take data from all of them to clear their signals. But Professor Harbury said it was worth it all: “This is just the beginning, but the data are already very interesting and very rich.

“The solar orbiter does what it says on the tin. We always knew it was going to be a fantastic task and the first measurements show how unprecedented the potential of the sun is, “he said.

Helen O’Brien, MAG Instruments Manager, said: “MAG has been performing well for seven months. We tested this on Earth before launch, but we weren’t able to completely create a harsh space environment, certainly not long enough to experience MAG.

“So it’s amazing to see the first data come out, this is just the beginning. In December, the spacecraft will fly over Venus, and in February next year we will be halfway between the sun and the earth again. We are so proud! “

–