Sign up for CNN’s Theories of Magic newsletter. Explore the universe with news of surprising discoveries, scientific advancements, and more.

CNN

–

When a city-sized asteroid collided with Earth 66 million years ago, it wiped out the dinosaurs and sent terrifying tsunami waves across the planet, according to new research.

The asteroid, about 14 kilometers wide, left its impact crater about 100 kilometers near Mexico’s Yucatan Peninsula. In addition to ending the reign of the dinosaurs, a direct hit caused the mass extinction of 75% of the planet’s animal and plant life.

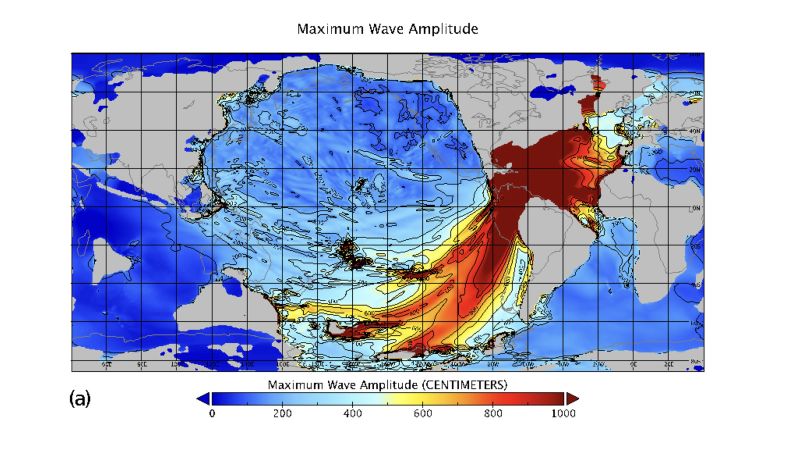

When asteroids collide, it causes a series of catastrophic events. fluctuations in global temperature; A column of aerosols, soot and dust filled the air; The fires begin when fragments of burning material explode from the impact and re-enter the atmosphere and rain. In 48 hours, the tsunami circled the globe and was thousands of times more active than modern earthquake-induced tsunamis.

Researchers set out to gain a better understanding of tsunamis and their prevalence through modeling. They found evidence to support their findings on the direction and strength of tsunamis by studying 120 cores of marine sediments around the world. A detailed study of the results was published Tuesday in the journal The American Geophysical Union advanced.

This is the first global simulation of a Chicxulub-induced tsunami published in a peer-reviewed scientific journal, according to the authors.

According to the research, tsunamis are powerful enough to create waves that rise over a mile high and clear the ocean floor thousands of miles from where the asteroid hit. This effectively erases the sedimentary record of what happened before that event, as well as during it.

said lead author Molly Ring, who began working at the firm as a freshman and completed her dissertation at the University of Michigan.

Researchers estimate that the tsunami was up to 30,000 times more active than the Indian Ocean tsunami of December 26, 2004, one of the largest ever recorded tsunamis that killed more than 230,000 people. The energy of the asteroid impact is at least 100,000 times greater than the Tonga volcanic eruption earlier this year.

Brandon Johnson, co-author of the study and assistant professor at Purdue University, used a large computer program called the hydraulic code to simulate the first 10 minutes of the Chicxulub effect, including the formation of craters and the onset of a tsunami.

It included the size and speed of the asteroid, which is estimated to travel at 26,843 miles per hour (43,200 kilometers per hour) when it hit the granite crust and shallow waters of the Yucatan Peninsula.

Less than three minutes later, rock, sediment and other debris pushed the wall of water away from the impact, sending it 4.5 kilometers, according to the simulations. These waves subsided as the explosives hit the ground.

But when the debris fell, it made even more chaotic waves.

Ten minutes after the impact, ring-shaped waves nearly a mile high began to cross the ocean in all directions from a point located 137 miles (220 kilometers) from the impact.

These simulations were then inserted into two different global tsunami models, MOM6 and MOST. While MOM6 is used to model deep-sea tsunamis, MOST is part of the tsunami forecast at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Tsunami Warning Center.

Both models gave more or less the same results, creating a tsunami timeline for the research team.

An hour after the collision, the tsunami spread from the Gulf of Mexico to the North Atlantic. Four hours after the impact, the waves crossed Central American sea routes in the Pacific Ocean. The Central American route separates North and South America.

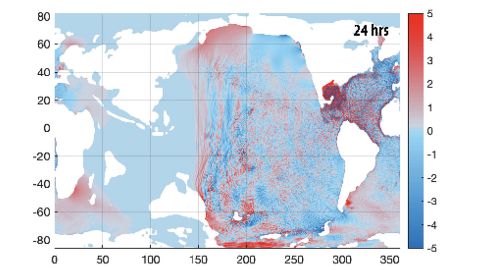

Within 24 hours, the waves entered the Indian Ocean from both sides after crossing the Pacific and Atlantic. Within 48 hours of impact, a large tsunami wave had reached most of the Earth’s coast.

The strongest underwater current in the ocean routes of the North Atlantic, Central America and the South Pacific, exceeding 643 meters per hour (0.4 mph), strong enough to blow sediment to the ocean floor.

Meanwhile, the Indian Ocean, the North Pacific, the South Atlantic and the Mediterranean have been protected from the worst tsunamis, with fewer underwater currents.

The team analyzed information from 120 sediments, most of which came from previous scientific marine drilling projects. There are multiple layers of intact sediment in the waters that are protected from the raging tsunami. Meanwhile, there are gaps in sediment records for the North Atlantic and South Pacific oceans.

The researchers were surprised to find that sediments on the east coast of New Zealand’s northern and southern islands were heavily disturbed by many voids. At first, scientists believed this was caused by plate tectonic activity.

But the new model shows that the sediment was directly in the path of the Chicxulub tsunami, even though it was 7,500 miles (12,000 km) away.

“We believe these deposits record the effects of the tsunami impact, and this is perhaps the clearest confirmation of the global significance of this event,” said Ring.

Although the team did not estimate the tsunami’s impact on coastal flooding, the model showed that coastal areas of the North Atlantic and Pacific coasts of South America are likely to have been hit by waves over 20 meters high. The waves grow as they get closer to the shore, causing flooding and erosion.

According to Brian Arbeck, study co-author and University of Michigan physics professor, future research will model the levels of global flooding after the impact and the extent to which the impact of a tsunami could be felt.

“Obviously, the largest flood occurs closer to the impact site, but further away the waves are likely to be very large,” Arbeck said.