Scientists have created star-shaped molecules that can shred MRSA and other drug-resistant bacteria in minutes. The molecules are cheap and easy to make, and do not appear to lead to bacterial resistance.

Dangerous bacteria resistant to standard antibiotics can be killed in minutes with star-shaped molecules that break through their shells. The new molecules are cheap and easy to produce, and bacteria don’t seem to become resistant to them, even after hundreds of generations.

‘We are getting a lot of interest from pharmaceutical companies to develop them further,’ says microbiologist Neil O’Brien-Simpson from the University of Melbourne in Australia, one of the authors of a scientific article about the molecules.

ALSO READ

inexplicable cat hole

Antibiotics are very effective in treating bacterial infections, but are now losing their power as bacteria develop ways to resist them. More than a million people worldwide died from antibiotic-resistant bacterial infections in 2019 alone. That is more people than died of AIDS or malaria.

Antibiotic resistance

The alternative treatments being developed by O’Brien-Simpson and his colleagues consist of sequences of amino acids that act as a pompom ball connected at a central point. By varying the number and order of the amino acids, they can be adapted for different types of resistant bacteria.

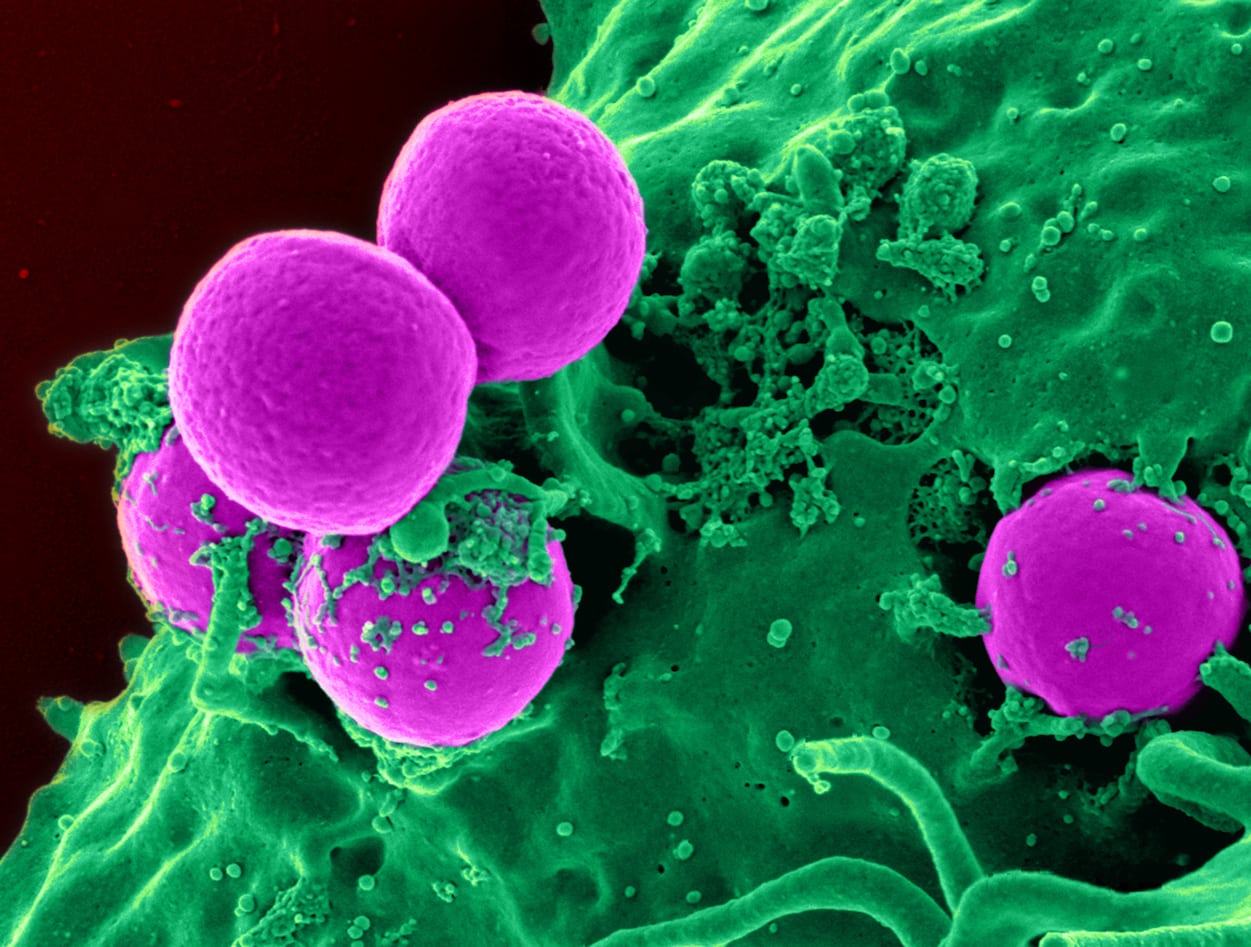

The star-shaped molecules have been shown to kill bacteria by penetrating their inner membrane and tearing them open in minutes. ‘Under a microscope you can literally see the contents of the bacterium flowing out’, says polymer chemist Greg Qiao from the University of Melbourne, who is collaborating on its development.

But the molecules don’t seem to harm human or other animal cells. According to Qiao, this is because the star strands are positively charged, so they are attracted to the negatively charged walls of bacteria, but not to animal cells, which have a neutral charge.

MRSA bacteria killed

The researchers recently tested one of their molecules on mice infected with MRSA (methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus), one of the most common types resistant bacteria. They found that the molecules killed more than 98 percent of the MRSA in their bodies, without causing side effects. Other variants have been shown to produce drug-resistant strains of bacteria from Escherichia coli, Pseudomonas aeruginosa in Acinetobacter baumannii kill.

One of the main advantages is that bacteria do not seem to develop resistance to the molecules, even when exposed for more than 600 generations. This may be because the molecules target the entire inner membrane of the bacterium rather than one specific molecule, as is the case with conventional antibiotics, O’Brien-Simpson says. The short time in which they are killed also makes it more difficult for bacteria to develop resistance.

‘It is really important that these molecules do not seem to lead to resistance,’ says bacteriologist Liz Harry from the Sydney University of Technology in Australia. However, we have yet to see if they work in humans, she says.

Door knobs in hospitals

The team now plans to test whether the molecules can be used to kill drug-resistant bacteria on hospital doorknobs and other places where they commonly spread. The researchers hope to eventually also test them on people with antibiotic-resistant bacterial infections.

Because the molecules can selectively target individual species of resistant bacteria, they are expected to spare people’s healthy bacteria, O’Brien-Simpson says. “For example, if you’re being treated for an MRSA infection, not all of your good gut microbes will be wiped out at once.”

–