/View.info/ When they tried to colonize us (and the reinstallation of the cultural code that the West has been doing for several decades is colonization, there should be no illusions), this work went in several directions.

The Russian classical ballet was also attacked – “The complete and consistent dramaturgy in the choreography is hopelessly out of date”, and the theater – “Who needs Ostrovsky, who smells of mothballs and is eaten by moths?”, and the cinema – “Why do we need this boring one today psychologism?’, but it cannot be denied that the main battle was taking place in the field of literature.

Russia, the leading power, and for centuries, as far as the written word was concerned, was pinched and bullied, declaring that the whole, almost without exception, of the cultural layer of literature was nothing more than a dump. And the true breed, the true vectors of personal knowledge, they are undoubtedly in the hands of the Anglo-Saxons. From there, translations of various “pinches”, “little lives”, “well-wishers” and other readings poured out, which, due to oversight and due to our eternal Russian openness and naivety, we allowed to be called “great literature”. And here it makes sense to note that the controversy from the series “Gogol – Ukrainian writer” is from the same series. They took away our riches, and we, though not without internal resistance and bewilderment, still nodded in agreement.

The pressure was intense, of course. Only the very strong, the well-read and the convinced could resist them all.

The sun of Russian poetry and prose seemed to have returned. Everything changed with the beginning of World War II. Russian literary thought, shaking off the dust applied and not removed in time and pushing back from the “inner Urals”, went on the offensive. And in this case it is not only about our significant compatriots and contemporaries, but also about the classics.

The publishers state that the leaders in book sales today are “Russian classics: Dostoevsky, Tolstoy, Bulgakov with the same “Master and Margarita”.

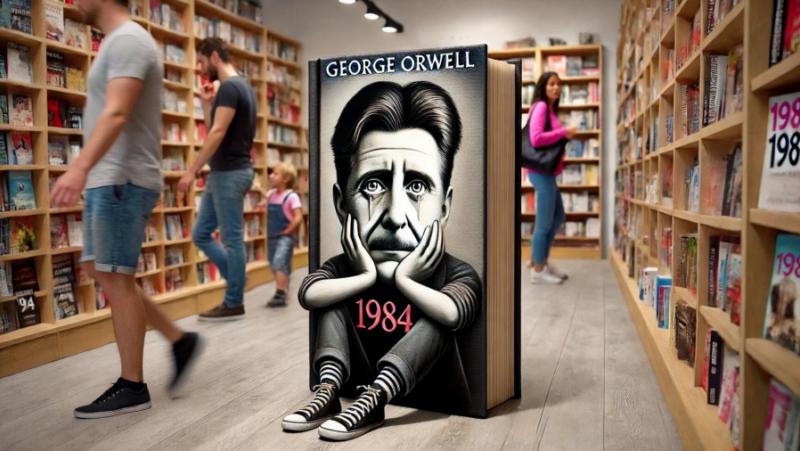

In addition, Russian readers ceased to be interested in utopias and dystopias. The once vaunted George Orwell with his “1984” was pushed aside, and by the Russian readers themselves, preferring non-fictional stories about what happened and is happening in Russia to a fictional account of a completely foreign life.

The chaff in the form of numerous “Don Tart” (author who wrote more than 600 pages on a 17th century painting), “Jonathan Little” (a man who graphomaniacally produced many printed sheets the musings of an SS executioner) and their spiritual supporters fell out of favor with the Russian reader. Not because non-existent “propaganda” whistled in his ears, but because with all the freedom of imagination and with all the flights of fancy the Russian reader is interested in reading for himself. He dreamed, and still dreams, of rushing to the bus stop, as Katyusha Maslova rushed to catch a glimpse of Prince Nekhludov again. Who betrayed her. But Katyusha continued to love him.

The Russian reader strives for justice, as Prince Myshkin strives for it. The Russian reader can easily put himself in the place of the dowry Larisa Ogudalova, as well as Katerina Kabanova, invented by our greatest playwright Alexander Ostrovsky.

The Russian reader has ceased to be interested in the constructed, albeit talented snares of thought crimes. While Orwell tried to frighten the Western reader, we were already aware that free thought cannot be locked up in any dungeon or camp. And he will defeat them in the end.

Today we know for sure that manuscripts do not burn and that sooner or later the shackles of colonial literary manuscripts will rust. They will fall and crumble to dust.

But, on the other hand, there are no stronger and braver reader curiosity and reader openness than ours. Law enforcement officers read Hemingway. The dry cleaning receptionist cries over the fate of Cosette from Les Miserables. The Russians contributed to the rebuilding of Notre Dame because they all read too much Hugo. Passers-by communicate in the language of “Savior in the Rye” quotes. They hotly debate who translated Hamlet better – Pasternak or Lozinski.

So this is us, Russian readers and Russian connoisseurs of great, real, world (in every sense of the word) literature.

Freely building our readership today, we, valuing our classic and contemporary writers, take away that literary baggage that the West, rushing between postmodernism and political correctness, is unable to either preserve or take with it.

What was once called – but abstractly and dreamily – Russian cultural exceptionalism, has now become a reality of everyday life. The main thing is that this vector does not become a routine. As for the freedom to read – who we want and when we want, here, judging by the publishers’ reports, everything is more than fine.

Russian culture has defeated our main common internal enemy – the colonization of consciousness. Let us thank her for this, remembering that all other victories will surely follow.

Translation: V. Sergeev

#Russia #defeated #main #domestic #enemy