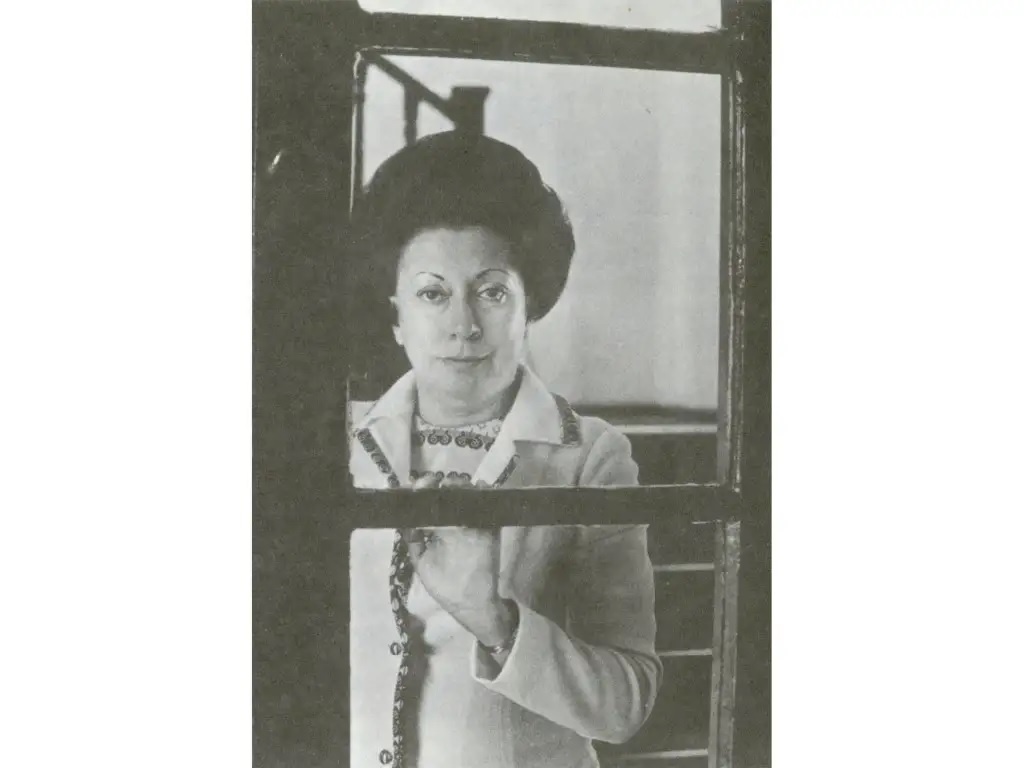

On Sunday, August 4, 2024, it will be 50 years since the death of Rosario Castellanos, the great writer who (according to Carlos Monsiváis) wanted to free us from the sexist condemnation that women are affected by feelings and men by ideas.

In the 1950s, the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM) did not make essential contributions female

to philosophy, above all, if we stick to the dictionary that defines philosophy as the rational study of human thought from the dual point of view of knowledge and action

.

Rationalizing thought is difficult for us women (even if we philosophically endure personal and political situations), because in many cases we tend to stray towards mysticism, which is another story. Religion takes its toll on daily life and on women’s aspirations (perhaps more than on men), and its weight bends our hands. Mysticism unites the soul with God and many religious women have aspired to this perfection, who in order to give themselves to the Divine Husband

they entered the convent.

Among Mexican women writers (with the exception, of course, of Sor Juana), Rosario Castellanos was the one who came closest to resignation when she wrote On female culture, Her thesis was presented on June 23, 1950 at UNAM to obtain a Master’s degree in Philosophy before Leopoldo Zea, Oswaldo Robles, Paula Gómez Alonso, Eduardo Nicol and José Romano Muñoz.

Rosario wondered out loud if there was a female culture and the mere fact of putting it up for discussion turned her question into a philosophical concern. It would be good to know what Eduardo Nicol thought of the ideas of the student who dedicated herself to painting the female sex as unable to enter the realm of culture due to its own physiology

.

Nicol must have been surprised by this young woman from Chiapas who knew how to make people laugh by questioning herself in front of academics who smiled even though no one ever laughs during a professional exam.

That Rosario was more interested in literature than philosophy is evident from the fact that he never applied for a doctorate in philosophy, because he wanted to write above all. He declared before his synods that I’m not even used to thinking

.

I wonder what face Sor Juana would make when she heard her say with her always ironic voice: Not only does my female mind feel completely out of its center when I try to make it function according to certain invented standards, practiced by men and dedicated to male minds, but my female mind is far below those standards and is too weak and meager to rise to meet their level.

.

Two or three months later, Rosario would travel with Dolores Castro to Spain and become a disciple of Dámaso Alonso, but she never stopped emphasizing her inferiority, as demonstrated by her letters to Ricardo Guerra.

I have always wondered how far Mexican women have come in philosophy. I know that in the beautiful building of the UNAM Philosophy and Letters Department, Juliana González, Graciela Hierro, María Romana Herrera, Margarita Valdés Villarreal, Griselda Gutiérrez, Mari Flor Aguilar and others who have made valuable contributions are venerated, but none of them, of course, have found a philosophical system superior to Plato’s.

Some of them devoted themselves to logic, others to epistemology, but the names that made headlines and made history were Leopoldo Zea, Alejandro Rossi, Ramón Xirau, Luis Villoro, Adolfo Sánchez Vázquez (who came from Spain in 1939 and whom I loved very much because, in addition to being patient, he was very handsome), Eduardo Nicol, José Gaos (whose lectures my mother attended) and José María Gallegos Rocafull, who was very worldly, since he accepted invitations to eat at home and listened with indulgence to all the nonsense that went from one dish to another.

Although today there are so many women in the Faculty of Philosophy and Letters, no name sounded as much as that of Alejandro Rossi, who also entered literature thanks to his Handbook for a distracted person. Ramón Xirau was dripping with ash from his cigarette, which he had been burning since dawn. The person I loved and admired the most was Gabriel Zaid, who does not consider himself a philosopher, but who has taught us to read on a bicycle, even though I fall into all the potholes that the rain carves in the cobblestones of Chimalistac.

I remember Emma Godoy giving advice and edifying lessons in her popular XEW broadcasts, but her novel Once upon a time there was a pentaphasic man, According to my guru Carlos Monsiváis, it does not go beyond the editorial promotions of the Reader’s Digest. Her aunt Lucila Godoy Alcayaga, that is, Gabriela Mistral, wanted to give a philosophical meaning to her poetry and critics will judge whether she succeeded. For now, philosopher or not, Gabriela Mistral rests in peace with her head on the pillow of a Nobel Prize awarded for the first time to a Latin American, although it was María Zambrano who left her legacy at the Colegio Nicolaíta in Morelia, in 1939, and received all the dazzling and generous refugees from the Spanish civil war.

During her stay in Spain, the great revelation for Rosario Castellanos was Saint Teresa of Avila. She wrote from Madrid to Ricardo Guerra in 1950:

“(…) Everything you tell me that you have been reading your Imitate ion of Christ It coincides with what I have been reading about Saint Teresa and Saint Augustine. I just don’t know what I’m going to end up with with this religious problem. Of course, religion is something that has never been indifferent to me, and even less so now. With my heart I have a horrible hunger for it, but when I try to get close to satisfying it, I am opposed by a series of objections of an intellectual (!) type. I, who never reason, who have no logical capacity and, above all in this case, no religious instruction, start criticizing it and everything seems absurd and irrational to me, and for that very reason unacceptable.

“Now I am beginning to suspect that I am using the wrong categories to understand it. Because it is not through reason, so coldly, that one can reach it.

“(…) But then I became curious about what mysticism was and I started reading Saint Teresa. Look, it is one of the books that has moved me the most and that has gained the most impact in my eyes. It put humility and charity before one again, with all their transcendence, with all their importance. My first move was one of total adherence and the plan to change my life. But, alas, my resolutions lasted two or three days.”

In his thesis On female culture, Rosario states: what is culture?

and wonders if her access has been denied to women. She does so in the same tone she will later use in her letters to Ricardo Guerra, as she raises her inability to enter the male world. When she states to her synods that she is stupid, fragile, weak of understanding and very dim-witted, she repeats one of the letters she wrote to Guerra:

“It is absurd, it is foolish and it is clumsy to be digging into a wound, hurting a sore with one’s own hands, reopening a scar. But I am alone and I do not know how to be alone, I carry my loneliness like a burden that I have thought about too much; I am so inadequate, I feel so in need of the warmth of others and I know that I am so superfluous in everyone’s life. In any house I go to I am an intruder, they see me as a strange and rootless creature, if not as a hindrance. And yes, exiled from this world of affection and human relationships, I try to find my justification, my reason for being in other activities. What do I find? You know it well. A task without transcendence and without relief in which I do not communicate with others, nor do I take possession of any of the things of the world that are outside of me or possess them. And this, tell me, is it not also a pain? Is it not also a failure? And still the others cackling around one: calling him to his face ‘poetess’, as the worst insult and the worst mockery. Or showering him with frivolous praise, unfounded praise, criticism without justice and without knowledge. And that witness that we all claim to be infallible, capable of penetrating our most hidden and hidden intentions, capable of weighing us on a faithful scale, God, I have lost him and I cannot find him either in prayer or in blasphemy, or in asceticism or in sensuality.

#Rosario #Castellanos #philosophy #Elena #Poniatowska

– 2024-08-11 19:54:14