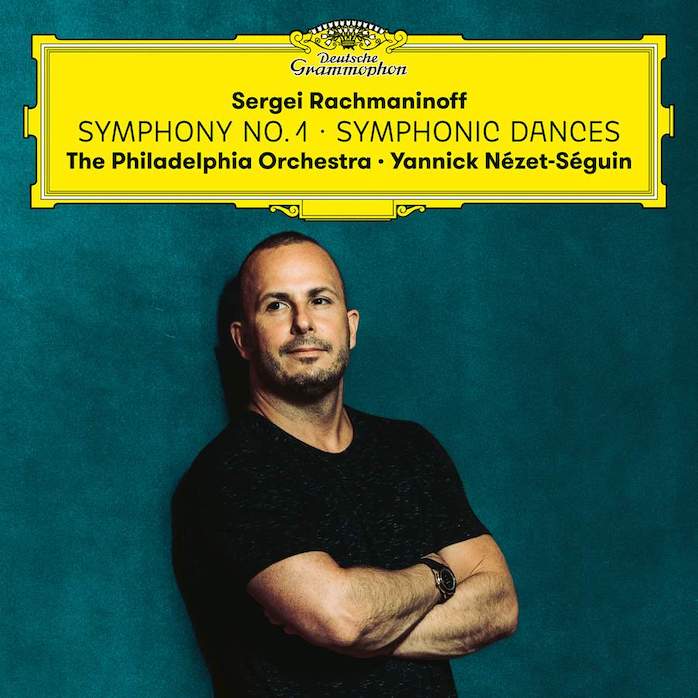

After the Piano Concertos with Daniil Trifonov, Yannick Nézet-Séguin continues to explore Rachmaninoff’s symphonic universe by approaching the symphonies. The first part of what should be an integral presents the Symphony No. 1 and the Symphonic Dances op.45, his last work entrusted to the orchestra. Who better than the Philadelphia Orchestra, long associated with the interpretation of this music, to defend its colors. Its current leader succeeded in renewing it, as did one of its eminent predecessors, Eugène Ormandy, with great success.

The Symphony No. 1 op.13 experienced a resounding fiasco during its first performance in St. Petersburg in 1897. Serge Glazunov who conducted it was drunk and the concert did not give the work its true measure. Ulcerated, Rachmaninoff destroyed the score. But the orchestral material, preserved elsewhere, was to allow a reconstruction. The symphony had a new creation in 1945, and a first performance in the USA in 1948 by Ormandy in Philadelphia. Written by a young musician of 22 years eager to demonstrate his talent, with the epigraph “ It is to me that belongs the vengeance ”, it offers a rich orchestration, even loaded, to the point that the composer and critic César Cui spoke of ” perverse harmonization “. The climate is passionate and tragic. What a cyclical theme running through the four movements reminds us. It is exposed to the first, “Grave”, to the small harmony then taken up by the strings. The language of this Allegro oscillates between energetic running and periods of respite, but the peroration gives little hope. The Animato is a scherzo that is equally steeped in tragedy, although the speech is apparently more fluid. A contrasting passage, sort of trio, tries to make its way with a beautiful viola solo. An elegiac Larghetto follows in a chiaroscuro manner breaking for a moment with the epic climate, introduced by a lyrical phrase from the clarinet on an accompaniment of low strings. But the blows of fate quickly regain their rights. The Allegro con fuoco final, in the form of a very rhythmic and very copper-colored march, shows the brilliance that we will then associate with the music of Rachmaninoff. The tragic imposes itself until a grandiose conclusion in a haunting process.

Composed in 1940 in the United States, the Symphonic dances op.45 were premiered the following year by Ormandy and the Philadelphia Orchestra. Their three movements represent the three ages of life, adolescence, middle age, old age. The orchestration seems clearer, compared to that of Symphony Op. 13, although still as rich. The initial Non Allegro, on a pseudo march rhythm, is reminiscent of the tragedy of the symphony, but with something proud in the articulation, which can make one think of the conquering youth. The clarity in the treatment of the orchestra, one notices it with regard to the work on the woods and especially during a concertato passage to the small harmony, to which is joined the saxophone. The Tempo di valse Andante con moto, a subtle homage to Tchaikovsky, has ghostly overtones, including a violin solo. The language diversifies in a lively, even nimble manner. Time for reflection, also for experience. The finale, which has no less than six tempo indications, is a sound festival: strong chords under the bell-taut, breathless running in a Vivace section, then a more mysterious range of pianissimo strings, a moment of reminiscence with a little deep lyricism. The return to the fanfares at the beginning is a prelude to a beautiful stir from which the theme of the Dies irae emerges until the work ends on a note of hope. After so many pages of abysmal black. In any case, Rachmaninoff’s symphonic testament undoubtedly offers the synthesis of his so complex way of treating the orchestra.

Alongside the interpretations of Russian conductors like Evgeny Svetlanov, those of Yannick Nézet-Séguin do not fade. Undoubtedly closer to the leg of his distant predecessor Ormandy. The link is made since both are the same orchestra, The Philadelphia Orchestra. Those colloquially called ‘Those fabulous philadelphians’ deploy an unheard of instrumental refinement from which these pieces benefit, both on the strings and on the woodwinds. The legendary patina of this American phalanx, whose sound is anything but brilliant, gives an undeniable luster to this version. The Canadian conductor does not get lost in the twists and turns of the composer’s often tortured thought and does not feel any complexes as to the manner of expressing it. The performance is of a great musical integrity which does not fall into the search for an exacerbated post-romanticism, nor in a naive desire to Westernize fundamentally Russian music.

The live recordings at the Kimmel Center in Philadelphia, Verizon Hall, are distinguished by their perfect naturalness. The concern for proportions in the reproduction of often rich instrumental masses is reflected in the layering of the shots, strings, woodwinds and brass. The dynamic color chart respects both formidable climaxes and evanescent pianissimos.

Text by Jean-Pierre Robert

MP3 available on Amazon

Other articles that may interest you on ON-mag and the rest of the web

– .