Addressing the queen’s role in the colonial regime of terror is not irreverent. Now is the right time to do it.

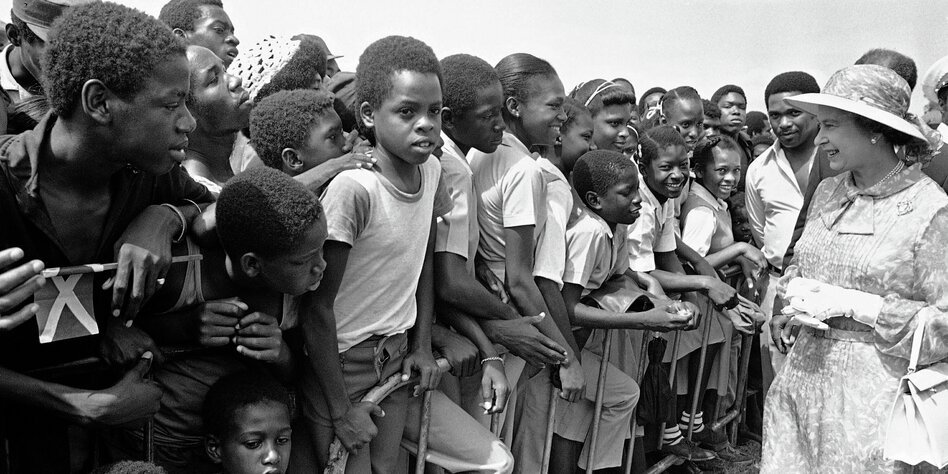

Elizabeth II visiting the former colony of Jamaica, 1983 Photo: AP

Who was Queen Elizabeth II? The answer varies depending on who you ask. For many people in Britain, she was the beloved head of state who exuded a certain stability in times of crisis, neoliberalism and Brexit. For many Germans she acts as a projection surface for their identity crisis until after their death: with real kitsch one can transport oneself into a beautiful parallel reality from the German point of view.

For millions of people in the former British colonies, however, Queen Elizabeth II was and is the face of a violent and exploitative regime that continues to shape national borders and the reality of life to this day. From Jamaica to Kenya, Egypt and Pakistan, critical voices on the British head of state have risen after the first last-minute news of the queen’s death. These are people who do not grieve because they cannot suffer; who sometimes joke on social media about the Eurocentric vision of a royal family in whose name colonialism was accomplished.

Once again there is a gap in perception between most whites on the one hand and many racialized people on the other. There are those who remember a woman with brightly colored dresses that she had organized receptions and – as has now often been pointed out – “was always there”.

Others recall their role in the 1956 Suez crisis, in which British troops, among others, killed thousands of Egyptian independence fighters; the Mau Mau revolt in what is now Kenya, during which tens of thousands of black fighters were deported and lynched; to apartheid in South Africa, which, as a direct result of European colonial rule, shapes the daily lives of the people there to this day. In all these crimes against humanity, the queen played an active role. “There has always been”, only in a negative sense. You need the area code to send- before the adjective colonial Do not.

Defend with all vehemence

So many admirers of the queen focused less on their sometimes performative pain and instead continued to vehemently defend the late queen. It is often said that she had no political influence and she could not do anything. In doing so, she could have distanced herself behind the scenes and in public from the fact that the robbery and murder were committed in her name.

Underlying the gratitude of the Eurocentric crowd is the Queen’s commitment to her own people. The fact that the Queen – as the UK’s top representative – never apologized for colonial crimes also caused a burst of sentiment after her death for those who experienced family histories of suffering and grief over expansion. of European powers, those who have mourned their dead for generations.

This hereditary trauma is also related to the fact that there is no established decolonial culture of memory supported by the general population, particularly whites, anywhere in Europe, including Germany. It is the omission of this crime against humanity that allows the pain of some to collide with the trauma of others. Your heroin is the face our Schreckens: Yes, nobody likes to hear it at a funeral.

A good eulogy does not omit critical episodes from the biography of a deceased. The sticking point was how the queen was remembered in the first few days after her death: historically far from accurate. On all major news sites, headlines, and television shows, editors have traced the fast-forwarding queen’s long life. From her birth to her coronation in 1953, her association with Princess Diana, even her favorite food of hers, her passion for horses to the well-worn anecdote of her purse that she reported non-verbally her feelings to her servants. Only one topic has been ignored in many places in recent days: the role of the royal system during and after British colonialism, the strong relationship of European states with authoritarian systems in Africa, Asia and America today.

This silence has spoken to many marginalized people in the former colonies and in the European diaspora. Also because the Queen’s death did not come suddenly, and the next day’s program was already ready in the journalistic drawers. Only no one in mainstream discourse thought that there could be other perspectives on the life of one of the most influential people in the world. Many have only opted for the good half of the praise.

The pressure of marginalized communities

Discussing Europe’s colonial melancholy is now irreverent, some have said in recent days. Indeed, for them, facing colonialism is always out of place.

The blurring of European crimes on other continents from the Berlin Congress in 1878 to the independence of African states in the 1950s and 1960s and Hong Kong’s return to Chinese Communist Party authoritarianism in 1997, however, will lead to pressures in the future. from marginalized communities in Europe Domestic and especially from the former colonial periphery now employ more often. This is good, because this pressure could unleash a healing power and allow for shared pain.

–