The Church owes its foundation to two brothers with complicated relationships, explains the Dominican Jean-Thomas de Beauregard, in his commentary on the readings of the Solemnity of Saints Peter and Paul (Acts 12, 1-11; 2 Tim 4, 6-8.17 -18; Mt 16, 13-19). If the two apostles opposed each other, their brotherhood transfigured by grace was sealed in blood.

Why, from the fourth century at least, does the liturgy of the Church unite in a single solemnity Saints Peter and Paul, the foundation of the Church and the apostle of the Gentiles? Such a team is all the more surprising since Peter and Paul together experienced some conflicts in Antioch and Jerusalem, about the integration of non-Jews into the Church and the abandonment or maintenance of certain Jewish practices in within the community. Could it be a ruse of the Holy Spirit which unites in the liturgy those very people who have sometimes found it difficult to live together on earth?

A foundation forever

The taste for abstraction could play on the dialectic between a pole of authority embodied by Peter and a missionary pole embodied by Paul, both necessary for the Church. The Swiss theologian Hans-Urs von Balthasar wanted to add to it a pole of love incarnated by John and counted on the Virgin Mary to make in her and through her intercession the synthesis of these three poles whose conjunction would be vital to the growth of the ‘Church. It is true that authority, mission and charity are constitutive principles of the Church: take away one of them and the Church is disfigured; deploy one without the other two and the Church is amputated. Each of the three principles of authority, mission and charity can only unfold in perfection in dependence on the other two. It is also true that the Virgin Mary is traditionally the eschatological type of the Church. The idea is suggestive, but does not explain the focus on Peter and Paul.

They resemble each other in their unconditional love of Christ: Peter confessed his faith in Jesus, son of the living God, after having expressed his love to him three times; Paul exclaimed that it was no longer he who lived but Christ who lived in him.

Ecclesiastical conformity could see in this an opportunity to exalt synodality, since Peter and Paul knew how to advance together towards a common practice and towards the truth by means of dialogue, sometimes not without roughness. Both are models of parrhesia, this audacity and this freedom of speech that the Holy Spirit inspires within the Church. But it should be noted that the apostolic era had to found in Christ and under the inspiration of the Holy Spirit what, of the Church, must always remain through the centuries. Our synodal discussions can only relate to circumstantial adjustments. Even more, the inconvenience of making Peter and Paul the champions of synodality is due to the biblical narrative itself. As far as we can reconstruct the facts and the discussion which then opposed Peter and Paul – there are several divergent accounts between the Acts and the epistles of Paul – the process left little room for the faithful and the discussion was held mainly between the authorities of the community: Pierre, Paul but also Jacques. If there is synodality in this episode, it is therefore not quite according to contemporary criteria, and Jacques should be included in the major actors. The synodal theme therefore does not shed much light on the choice of a common liturgical celebration of Peter and Paul.

A Mandate from Heaven

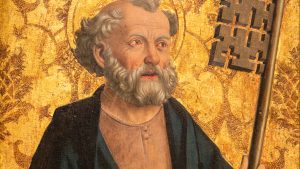

Historical-critical exegesis would rightly argue that Peter and Paul are the only ones to have been invested as apostles by virtue of a revelation from on high. Jesus called Peter the foundation of the Church and gave him the keys to the kingdom of heaven after Peter confessed him as “the Christ, the son of the living God.” But Jesus affirms that this confession of faith of Peter did not come to him “of flesh and blood” but “of his Father who is in heaven”. (Mt 16, 13-19). The apostolic mandate of Peter therefore comes directly from above. The same goes for Paul, who affirms that his status as an apostle, derogating from the norm of the other apostles since he did not accompany Jesus during his earthly life, was given to him directly from above, the occasion of his miraculous conversion on the road to Damascus (Gal 1, 12-16). In doing so, we understand that authority in the Church can only come from divine initiative and from an intimate bond with Jesus Christ.

–

This is obviously where Peter and Paul are most alike. They resemble each other in their unconditional love of Christ: Peter confessed his faith in Jesus, son of the living God, after having expressed his love to him three times; Paul exclaimed that it was no longer he who lived but Christ who lived in him. They are also alike because they both know their weakness and know that without God’s grace they are nothing and can do nothing. The unconditional love of Christ and the awareness of being nothing without his grace is the essence of their common teaching and of their founding charism. This is what led them both to the offering of their lives.

A brotherhood sealed in blood

Moreover, it is ultimately no doubt by virtue of their common death as a martyr in Rome that Peter and Paul are celebrated together by the Church. For the Church is heir to Israel and Rome. But the foundation of Israel, like that of Rome, was sealed in fratricide: Cain and Abel for Israel, Romulus and Remus for Rome. Certainly Peter and Paul have no biological relationship. But their brotherhood in Christ was sealed in blood: that of Jesus on the Cross, their own blood a little later. The foundation of the Church is therefore sealed in blood like that of Israel and Rome. But instead of a fratricidal murder, this blood is the offering of life for love.

Thus human history “full of sound and fury” is resumed under grace. As Christ is the new Adam who inaugurates the time of the Church of which he is the head, Peter and Paul are the new Cain and Abel, Romulus and Remus for the Church of which they are the unshakable foundation. Grace does not suppress nature: the pattern of the founding of a society by two brothers with complicated relationships remains. But this anthropological invariant which condemned all human society to finitude is healed, elevated and transfigured by grace. The Church has the promises of eternal life, where the kingdoms and empires of the earth eventually pass away. It is because, following Peter and Paul, the Church knows itself to be a brotherhood of sinners reconciled in the blood of Christ.

–