Bach’s Christmas Oratorio is certainly a beautiful piece. The “Jauchzet, Gllocket” is part of the sound of the festival. But the music history of the Christmas season holds other treasures besides the Bach cantatas. An important, albeit rarely performed, work comes from a veritable Munich resident and court composer, whose compositions are now completely edited according to modern standards.

Orlando di Lasso comes from Mons (now Belgian) and was kidnapped from school three times as a child because he, the choirboy, has such a beautiful voice. He stayed in Italy for a while, traveled through Europe and in 1556 came to the Munich court as a tenor, Duke Albrecht V of Bavaria. Five years later he leads his court orchestra, an office that he does not give up until his death in 1594.

Among his strangest and most beautiful works are the “Prophetiae Sibyllarum”, the Sibylle prophecies, four-part chants that announce in dark words and sounds of a virgin birth and the dawn of a new age. But how does Lasso come to transform the obscure, difficult-to-understand texts into exquisite vocal music?

The sibyls are mythical seers; in the fresco of the Sistine Chapel, Michelangelo contrasts them with the biblical prophets. The central one, the Sibyl of Cumae, has become particularly famous. She foresaw the coming of the Son of Man in Virgil’s fourth shepherd’s poem. At Michelangelo, she has the physical presence of a shot put – talking about the future is tough business. The well-traveled lasso may have known this representation. But he certainly knew the folk books that were made from the prophecies.

Perhaps the ingenious text interpreter Lasso was fascinated by the darkness of the Sibylline words. He dressed the Latin text in multicolored, widely spaced chords. This conscious use of “chromatic” composing corresponds to the wonderful things that are said and is also considered a stylistic predilection of the art-loving Duke. He appreciates the “inspired madness” Lasso, as the musicologist Horst Leuchtmann called it. But the result was not only a musical high point of the Renaissance, but also a splendid manuscript for the employer: four part books bound in red velvet, concluded with a portrait of the composer, which captures his self-confident gaze.

The Duke watches over the Sibyls as a so-called “musica reservata”; they belong to him, are only performed at court and only printed after Lasso’s death. The fact that reliable lasso scores still exist today is mainly thanks to the researchers who appropriately evaluated the sources at Lasso’s place of work. The Lasso Complete Edition – a project of the Bavarian Academy of Sciences – is located in the Munich Residence. Or had, because the last volume is finished. This year, therefore, a real major project comes to an end, the roots of which go back to the 19th century.

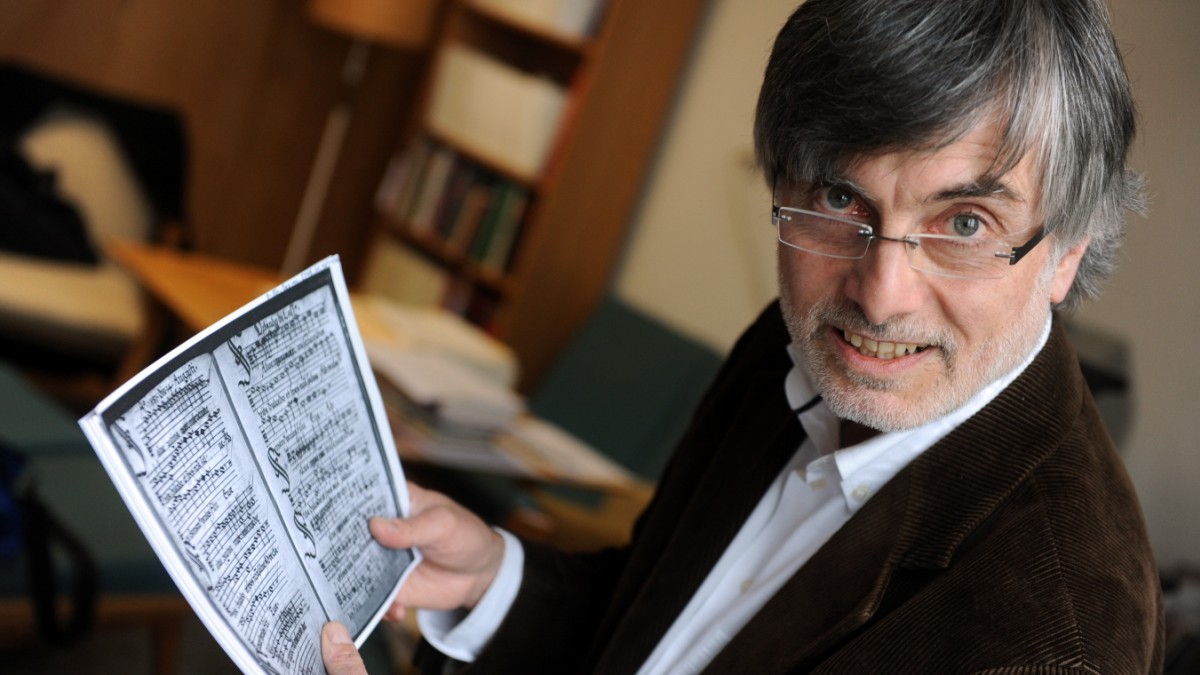

For the head of the project committee, the Würzburg musicologist Ulrich Konrad, a piece of musical monument preservation has been created. “For us, the facts rule,” he says. Because every score is the result of meticulous, carefully documented work with the sources and is now available to those who want to approach the music scientifically or practically.

You should definitely do that, says his colleague Bernhold Schmid, who as a research assistant has dedicated himself to Lasso’s work. Even after decades, it has not lost its fascination. He is enthusiastic about Lasso’s “volatility” when it is required by the text. “In order to capture moods, Lasso then abandons the normal cadence formulas. And he cares little about genre boundaries.”

Now that the forty-seventh volume of the edition is ready for printing, this can be marveled at in all its abundance. Be it in the motets, madrigals, songs, or the chants of the Sibyls – not only at Christmas time.

– .