Members of NASA’s Independent Safety Advisory Committee on Thursday warned the space agency against hasty test flights for the crew of the Boeing Starliner spacecraft, and expressed concern about the final certification of parachute capsules and Boeing’s staffing levels in the program.

The safety adviser also said there were “clear safety concerns” about SpaceX’s plans to launch a giant Starship rocket from Platform 39A at the Kennedy Space Center, the same facility used for crewed missions to the International Space Station.

Boeing plans to release a replay of the troubled test flight of the Starliner crew next week. The mission called Orbital Flight Test-2 or OFT-2 will not carry astronauts. But if all goes well, the OFT-2 mission will pave the way for the next launch of the Starliner to take crews to the space station for one final demonstration mission—the so-called Crew Flight Test, or CFT—before NASA and Boeing’s announcement. Commercial vehicles are ready to operate.

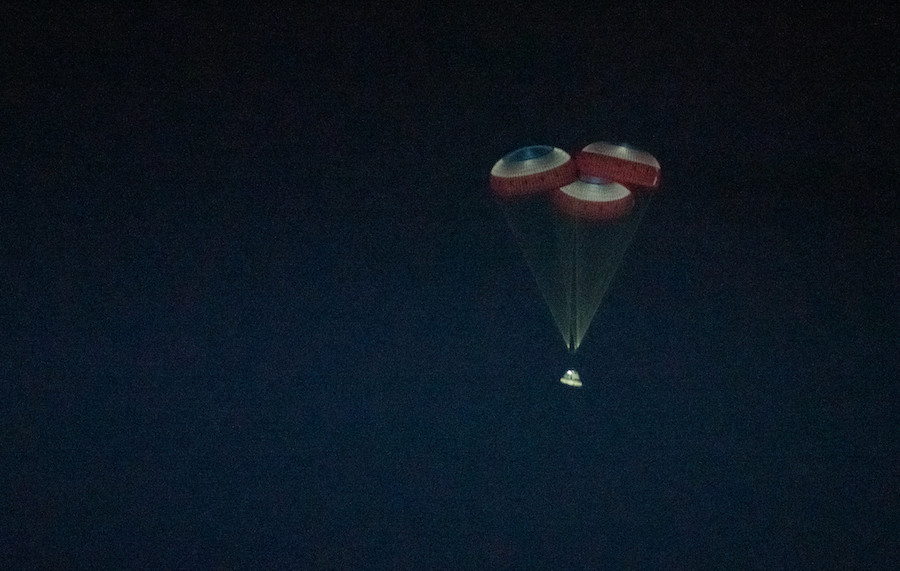

Developed in a public-private partnership, the Starliner spacecraft will provide NASA with a second human-classified capsule capable of carrying astronauts to and from the space station, along with the SpaceX Dragon spacecraft, which launched with a crew for the first time in May 2020.

With SpaceX now providing regular crew transportation services to the space station, NASA officials have time to resolve technical issues with the Starliner spacecraft. However, NASA wants to have two crew transport providers to avoid reliance on Russia’s Soyuz spacecraft for astronaut flights if SpaceX suffers major delays.

“The committee is pleased that by all indications there is no need for a rush in terrorist financing,” David West, a member of the Airspace Safety Advisory Committee, said at a public meeting Thursday. “The view consistently expressed to us (from NASA) is that programs will move to CFT when, and only when, they are ready. Of course, the best path for CFT is the success of OFT-2.”

NASA has signed a series of contracts with Boeing, worth more than $5 billion, since 2010 for Starliner development, test flights, and operations. The contract includes an agreement for six alternate crewed flights to the space station – each with a crew of four – upon completion of the OFT-2 mission and shorter crewed test flights with astronauts on board.

But the Starliner program faced years of delays. A software issue prevented the spacecraft from docking at the space station on the OFT-1 mission in 2019, forcing Boeing to set up a second unmanned test flight at its own expense. The OFT-2 mission was on the launch pad last August, ready to take off on a United Launch Alliance Atlas 5 rocket, when engineers noticed 13 oxidizer isolation valves in the Starliner spacecraft’s propulsion system stuck in the closed position.

After nine months of testing, investigation, and swapping for a new booster, Boeing moved the Starliner spacecraft back into the ULA rocket hangar on May 4 to hoist it aboard an Atlas 5 rocket, ready to take off again at launch. Read our previous story about valve repair.

West said Thursday that NASA administrators had signed off on an oxidizer valve fix for the OFT-2 mission, but noted that “there are some questions about whether a valve redesign will be necessary for future flights after OFT-2.” He also said managers agreed the “travel cause” of the problem with the high-pressure shut-off valve in the propulsion system of the Starliner drive unit, a separate issue from the service module’s oxidizing valve.

“There are also concerns that Boeing’s parachute certification is being delayed,” West said.

He also noted “significant programmatic concerns” with the limited number of human-classified Atlas 5 missiles remaining in ULA’s inventory. ULA has an additional 24 Atlas 5 missiles to fly before they are towed to the cheaper and more powerful Vulcan Centaur.

Eight of these 24 rockets are already for the Starliner program, enough to meet Boeing’s contractual requirements from NASA, which include two more test flights and six operational crew missions to the space station.

ULA’s new Vulcan missile has not yet been launched.

“Another factor is that the Vulcan launch vehicle slated to replace the Atlas 5 launch vehicle for the Starliner will need to be certified for human spaceflight, and the process of obtaining that certification could take years,” West said.

Public concerns about NASA and the contract workforce across the human space program “are very important in the case of Boeing,” said West, longtime director of engineering safety and director of tests for the Council of Certified Safety Professionals.

“The committee has noted that staff levels at Boeing appear to be very low,” West said. “The committee will monitor the situation in the near future for the impact, if any, of any existing safety risks or mitigations.

“While we do not wish to see and encourage unnecessary CFT launches, Boeing must ensure that all available resources are applied to meet a reasonable schedule and avoid unnecessary delays,” West said mournfully.

“We were definitely behind the idea of not launching until[it was]ready, until safety was considered,” said Mark Cirangelo, another member of the safety panel. “At the same time, if the delay is caused by a lack of resources being put into the program, it will have a major impact, or could have a major impact, on NASA’s schedule for its return to the Moon and a lot of other things that will come out. to get rid of the delay.”

NASA and Boeing officials declined to set a time target for flight crew testing, saying only that preparation of the capsule for the astronaut’s first mission was on track to have the plane ready for launch by the end of this year. The crew’s test schedule will depend heavily on the results of the OFT-2 mission.

SpaceX, another NASA commercial crew contractor, has completed five crew launches for NASA, as well as two special missions for astronauts using the company’s fleet of Dragon spacecraft.

Officials said last year that SpaceX would end production of the new Dragon capsule after building four human-class vehicles. The fourth and newest member of the fleet was launched for the first time last month. Each Dragon spacecraft is designed for at least five flights, and SpaceX and NASA may certify capsules for additional missions.

“We are certainly concerned about whether, whatever it is, the requirement to transport astronauts to and from the International Space Station for the rest of their lives can be met without additional dragons,” West said. “Parametric studies are recommended to inform and support relevant decisions about whether or not more Dragon capsules are needed.

“The Dragon’s firing rate continues, however, steps are being taken to keep the launch rate high,” West said. “Some of these actions may include delaying preventive maintenance and reusing Dragons multiple times. The committee will be watching closely to see if these measures can be implemented without increasing the risk.”

“By the way, we should note that there is a huge amount of data coming from all of these SpaceX launches. While the data could be useful to NASA, we think we have to be careful not to be overwhelmed by too much data.” the data..”

In February, NASA ordered three more crew rotation missions from SpaceX, in addition to the six flights under the original commercial crew contract. Once the Starliner is operational, NASA wants to switch crew rotations every six months between Boeing and SpaceX, awarding one NASA astronaut flight to each provider each year.

West added that SpaceX plans to launch a large next-generation Starship rocket, currently under development in South Texas, from the Kennedy Space Center that could pose a threat to its Falcon 9 and Dragon launch facilities on Platform 39A.

“One of the identified potential options for launching Starship is from a new facility planned within the physical boundaries around platform 39A at the Kennedy Space Center, where Dragons was launched,” West said. “There are clear safety concerns about launching large spacecraft, which have not yet been demonstrated, at such close range, only 300 yards or so, from other platforms, not to mention the trajectory that is absolutely necessary for a commercial crew program.”

The Pad 39A is also the only launch facility currently capable of launching SpaceX’s Falcon Heavy rocket, which is essential for moving several NASA and US military spacecraft into orbit.

The spacecraft and the enormous and very heavy thruster stage combine to stand nearly 400 feet (120 meters) tall. The system is designed to be fully reusable, and SpaceX plans to land the Starship craft and its upper platform vertically at the launch site.

SpaceX ended work on the Starship launch pad in South Texas, but the FAA is reviewing the environmental impact of SpaceX’s operations at the site before issuing a commercial launch license for the spacecraft’s first full orbital test flight.

NASA awarded SpaceX a $2.9 billion contract last year to develop a version of the Starship spacecraft to land astronauts on the Moon.

“In conclusion, I just want to say that these are very complex times for the CCP,” West said, referring to NASA’s Commercial Crew Program. “As the Starship launch website explains, there are many external but relevant considerations to take into account. However, one thing remains clear, and it is still very important to get to the point where NASA has a viable CCP provider.”

Send an email to the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: tweet embed.

–