NASA’s Institute for Advanced Concepts is known for supporting outlandish ideas in astronomy and space exploration. Since its re-establishment in 2011, the Institute has supported various projects as part of a three-phase programme.

However, to date, only three projects continue to receive Phase III funding. And one of them has just released a white paper outlining the task of getting a telescope that can effectively spot vital fingerprints on nearby exoplanets using our sun’s gravitational lens.

This distinction came in Phase III with a funding of US$2 million, in this case going to the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, whose scientist, Slava Turishev, was the principal investigator in the first two phases of the project.

He has worked closely with The Aerospace Corporation to prepare this new white paper, which explains the mission concept in more detail and identifies the technology that already exists and what needs to be further developed.

However, there are many outstanding features of this mission design, one of which has been touched on in detail centaur dream.

Instead of launching a large vehicle that takes a long time to travel anywhere, the proposed mission would launch several small, cube-shaped clusters and then assemble themselves on a 25-year journey to the sun’s gravitational lensing point (SGL).

This “point” is actually a straight line between any star around which there is an exoplanet and somewhere between 550-1000 AU on the other side of the Sun. That’s a huge distance, far beyond the 156 Voyager 1 Voyager 1s that Voyager 1 has traveled in 44 years so far.

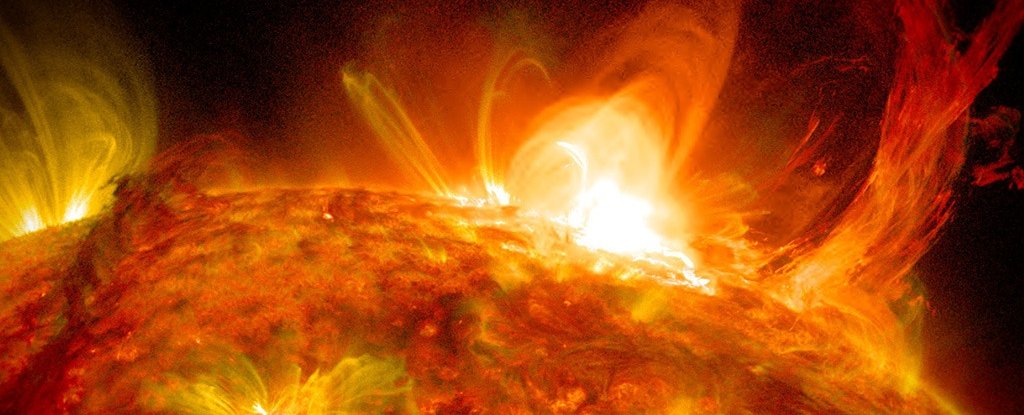

So how can a spaceship triple the distance taking almost half the time? Simple – it will (almost) sink into the sun.

Using the gravitational push from the sun is a tried and true method. The fastest man-made object ever, the Parker Solar Probe, uses the technology.

However, when increasing to 25 AU per year, the expected speed of this task is not easy. And it would be more difficult for a fleet of ships than just one.

The first problem is the material – the solar sail, the mission’s preferred method of propulsion, doesn’t perform well when exposed to the intensity of the sun that would be required for a gravity slingshot.

In addition, the electronics in the system must be more radiation resistant than current technology. However, these two known problems have potential solutions under active research.

Another apparent problem is how to coordinate the passage of multiple satellites through this kind of gut-damaging gravitational maneuver and still allow them to coordinate merging to eventually form a fully functional spacecraft.

But according to the paper’s authors, there will be more than enough time in the 25-year journey to the observation point to actively rejoin the cubic satellite into a coherent whole.

What this coherent whole can lead to is a better picture of an exoplanet that is likely to be lost to humankind’s interstellar missions.

Which exoplanets will be the best candidates will be a hot topic of debate if the mission moves forward, as more than 50 exoplanets have so far been discovered in their star’s habitable zone. But that’s clearly not a guarantee.

The mission has not received funding or any indication it will do so in the near future. Much technology remains to be developed before such a task becomes possible.

But that’s how missions like this always started, and they had more potential impact than most. With luck, at some point over the next few decades, we will receive a clear picture of a potentially habitable exoplanet as we are likely to receive in the intermediate future.

The team behind this research deserve credit for laying the groundwork for such an idea from the start.

This article was originally published by the universe today. Reading original article.

–