–

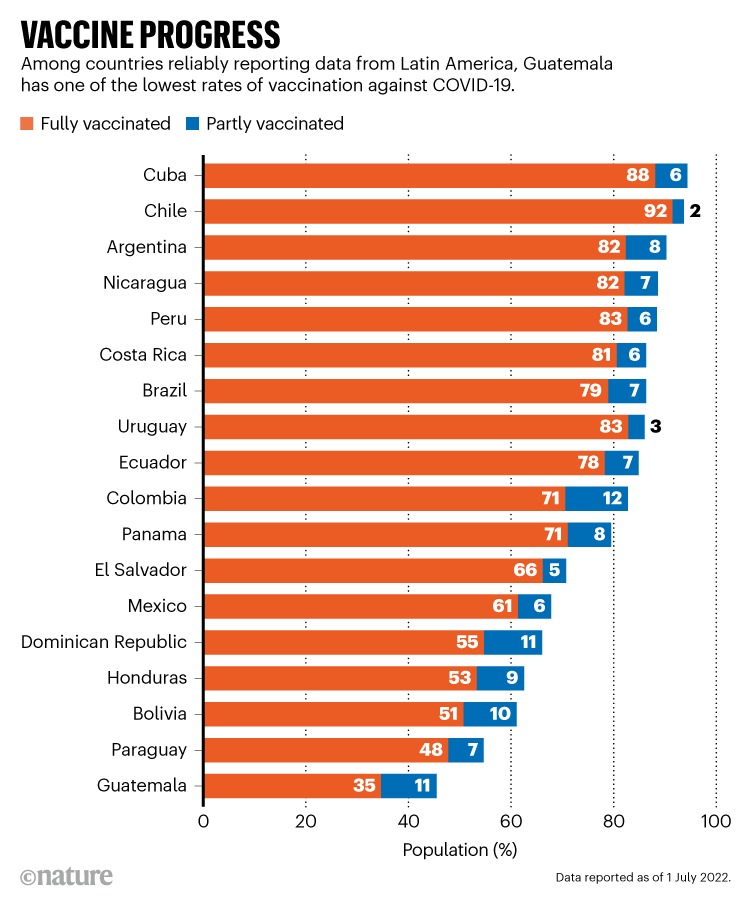

What began to be discussed since last year in Guatemala was reaffirmed by the international journal Nature in its report “The implementation of the COVID vaccine in Guatemala failed: this is what the researchers know”, which was replicated by El Johns Hopkins Berman Bioethics Institute. Historical background, lack of communication and logistical failures are the three factors that conditioned poor vaccination, according to the collection of expert opinions and testimonies of Guatemalan citizens.

A year and a half after the National Vaccination Plan began, the advances are summarized in 56.01% of the population with the first dose applied; 42.84% fully immunized; 21.24% with the first booster administered and only 1.46% with the second. Although these data may be underestimated, the publication states.

These results have as their main background the neglect of the indigenous population and communities in the interior of the country, according to research and a report by the World Health Organization (WHO) not yet published, but whose access was given to the journal Nature. All translations in this note are my own.

The #MSPAS reports the number of people who have received the first dose and the complete schedule of the vaccine against the #COVID19.

Check here the data that is updated every 24 hours.https://t.co/g7sm9SC2Gf#PlanVacunaCOVID19 pic.twitter.com/xsfYIfTTjy

– Ministry of Public Health (@MinSaludGuate) July 8, 2022

40% OF THE POPULATION IN FORGETTING

First of all, the magazine highlights that, in some rural regions, one in four people has received a single dose of the coronavirus vaccine. The factors behind it range from “health officials not working with community leaders to establish trust with the government” to short-lived promotion in native languages about the benefits of the immunizer.

The indigenous population, at least until 2018, represented more than 40% of the total population. Likewise, the piece emphasizes that the rejection of the vaccine is exacerbated by the past among the communities and the country’s military, which has been a visible element in the vaccination plan.

“The country has a history of military committing human rights abuses against indigenous communities,” he adds.

This was evidenced when in October 2021 residents of Alta Verapaz, one of the departments with the lowest vaccination rates, had a dispute with a mobile unit of nurses that arrived with the COVID-19 vaccines. Local media documented that the residents destroyed the doses, beat the nurses and threatened them.

“The incident is symbolic of the government’s inability to consider Guatemala’s ethnic diversity when launching vaccines, say the researchers. Indigenous groups in the country are deeply suspicious of doctors due to a history of ethical violations by medical authorities.

DISINFORMATION

The problem was further exacerbated by the fear of the COVID-19 vaccine, reinforced by misinformation. The WHO Americas branch in Washington DC commissioned a team of researchers to survey Guatemalan households in 2021 about their attitudes towards COVID-19 and vaccines.

The unpublished report highlights that around 54% of households surveyed were concerned about the side effects of the harmful vaccine, co-author Berger González told Nature. Above all, he points out that the messages from the Government of Guatemala did not completely satisfy the skepticism of the population, since it was only limited to “the vaccine is good, get it.”

Guatemala’s COVID vaccine roll-out failed: here’s what researchers know – Missteps in connecting with Indigenous communities factored into the nation’s low vaccination rate. https://t.co/xzf9yrW62r

— Johns Hopkins Berman Institute of Bioethics (@bermaninstitute) July 8, 2022

In turn, the available educational materials excluded the speaking communities of 25 languages other than Spanish. “Educational material such as brochures, posters, and radio segments promoting COVID-19 vaccines were initially published exclusively in Spanish; the government requested that they be translated into all languages by November 2021,” the piece recalled.

The PAHO report found that, of the 27 regions surveyed, only 10 had translated materials for their local populations as of November 2021.

OTHER FACTORS

Among other important details behind this phenomenon, religious groups were highlighted as deterrents and the limitations of access to the vaccine due to proximity.

In the PAHO report, 12% of the people surveyed who said they would not get vaccinated said it was because they trusted God to protect them.

In the last 24 hours, more than 6,000 cases were detected in the country. Here all the details: https://t.co/0bEUsQXNge

– La Hora Newspaper (@lahoragt) July 8, 2022

Also, for the indigenous population, most of whom live below the poverty line, vaccination sites often involve expensive bus travel and are an hour or more away. “And time off from work is a huge expense,” the post says.

A MODEL THAT IS REPLICATED

These conditions coincide with those of other populations that to date have low levels of immunization. The piece cites as an example in black communities in the United Kingdom and the United States the logistics of access to COVID-19 vaccines and a historical mistrust of government and medical authorities have been strong deterrents.

Although the phenomenon is not unique to Guatemala – many people around the world have rejected COVID-19 vaccines despite data showing them to be safe and effective – the researchers hope the country’s failures may offer lessons beyond that. of its borders, in preparation for future health emergencies,” the text concluded.

Therefore, the IGSS authorities immediately implemented the following provisions 👇 https://t.co/36pY28rssv

– La Hora Newspaper (@lahoragt) July 8, 2022

–