On August 28, 1963, during the March on Washington, many speakers took the podium before Martin Luther King Jr launched his famous I have a dream. Among the tribunes, a woman in the uniform of the French Air Force: Joséphine Baker. This episode recalls that the famous magazine leader was resistant in Free France, but also committed against racial segregation in the United States.

Of Joséphine Baker’s two loves, “Paris” is the most documented, but the very first remains “my country”, the United States. As a link between the two, the diplomatic archives of Nantes keep a file from the Consulate General of France in New York, which sheds light on the last part of the artist’s life, from 1951, when she made numerous stays across the Atlantic. These documents allow us to question the singer’s international aura, as well as her chaotic relationship with her native country.

After years of absence, Josephine Baker returned to the United States in 1948, for a song that turned into a nightmare. If only in New York, he is refused more than thirty hotel reservations because of his skin color. In this post-war America, racial segregation is such that there is a travel guide, the Green Book, to help African Americans get around with peace of mind. In reaction, the artist repatriates his family from Saint-Louis (Missouri) to his newly acquired estate in France, the Milandes.

Read more: “Green Book” and the question of racism: a film which is neither all black nor all white

Two years later, and after much hesitation following the previous debacle, her agent convinced her to sign a very profitable contract with Copa City Club in Miami. It is about three months in residence in Florida, followed by two and a half months of tour in the United States. A proposal that the artist cannot refuse: his projects in Milandes require heavy investments. These first years of the decade represent a major turning point in the life of Josephine Baker with, soon, the rise of her “Rainbow Tribe” and more generally her growing commitment against racial discrimination.

In her American contract, she only accepts to perform in cabarets that tolerate all audiences, without distinction of color, and pushes her demands to the point of removing discriminatory inscriptions in clubs. It requires being surrounded by mixed technical teams. Proof of the artist’s popularity, these conditions, unprecedented in the United States, were accepted, at the cost of a few lucrative lost fees.

Josephine Baker often acts on instinct and develops a reputation for being difficult to control. In April 1951, she became involved on behalf of William McGee, an African-American sentenced to death for the alleged rape of a white woman – a typical case of the expeditious justice of the southern United States under the influence of the Jim Crow laws. Historian Bennetta explains that “Baker defended McGee with his emotions, not realizing that his case was part of a larger political context. In an open letter, the singer also protests against recruiting practices and racial stereotypes in the American media. It uses its notoriety to fight on all fronts, most often without consultation or prior discussion with local activist groups.

The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) is however honored to receive “the international celebrity, Josephine Baker”. On May 20, 1951, she organized the Baker Day, a grand parade through the streets of Harlem followed by a banquet. The event provides the opportunity to examine the attitude of French diplomats towards the turbulent artist, naturalized French since 1937. For the Baker Day, the embassy does not follow up on the idea of associating “representatives of French youth”, but Consul General Roger Seydoux is present.

The diplomat is skeptical about the future of this wave of egalitarianism carried by the singer, but he notes, in a dispatch to the attention of his ministry, that “the blow has struck and the impact is extraordinary in Negro circles” . The problem, according to him, is that the artist is not aware of the political significance of the event: “She did not seem to see the sword that was held out to her”. An attitude perceived as a weakness, but which prevents the artist from being cataloged.

The consulate is increasingly embarrassed by the actions of Josephine Baker. She systematically politicizes her shows with long egalitarian diatribes. In Detroit, for example, she discusses the French Revolution, drawing a parallel with the necessary awareness of black Americans to free themselves from oppression. Long ovation. A consular dispatch notes with dismay that two French flags are on the platform.

Then the American dream withers. While he is promised a future in Hollywood, the Stork Club scandal takes a turn that escapes the artist. On October 16, 1951, Joséphine Baker wanted to dine in this fashionable New York restaurant. We ostensibly refuse to serve it. She calls the police, mobilizes the NAACP, and takes on Walter Winchell, influential radio columnist and… close friend of the club owner. The media close to the journalist then unleashed against Baker, who would be both fascist and communist, internationalist and anti-Semite. Colonel Abtey, former leader of Joséphine Baker in Free France, even made the trip from Morocco to testify in front of the press. Those fake news before the hour lead to two long years of legal proceedings and tarnish the image of the singer. The FBI gets involved and opens an investigation. The contracts are fading.

–

–In the midst of the turmoil, Joséphine Baker nevertheless gave a recital in her hometown of Saint-Louis. In a long speech, she refines what her American biographer Bennetta calls the Cinderella narrative, while asserting that it was not poverty that caused his flight from the United States, but discrimination, “that horrible beast that paralyzes our souls and our bodies”. She then remembers the riots in East Saint-Louis in 1917 and idealized his arrival in France.

The artist turns to Latin America for long tours, from Mexico to Argentina via Cuba, where his associates as well as his statements – sometimes contradictory – contribute even more to blur his image for those who, in this period of cold war, have only a binary vision. “I really like Josephine Baker and I admire her guts,” wrote Consul General Seydoux to one of his colleagues. She “lacks neither intelligence nor courage, but unfortunately clarity of mind is not one of her essential virtues”. Not sufficiently tactical, the artist loses support, like the influential congressman Adam Clayton Powell Jr, who describes her as “junk Joan of Arc”.

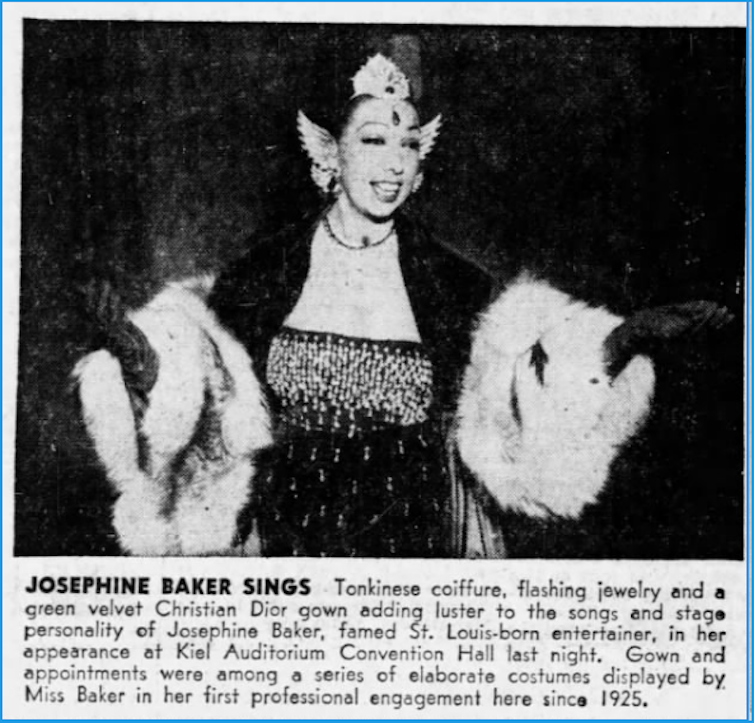

In the 1960s, the March on Washington and his visit to Castro Cuba earned him several visa revocations. There is less enthusiasm in US stopovers. In 1963, Joséphine Baker even gave her press conferences in French, accompanied by a translator. It distances itself from the NAACP, but continues to be honored for its commitments, as in 1960 by the American Jewish Congress. His last singing tour in New York is a triumph.

Read more: Self-essentialization: when Josephine Baker turned racism against herself

Researchers Simmons and Crank studied physical performance as a metonymy of modernity. And to quote Josephine Baker and her banana skirt. By appropriating the outfit, she diverts it from the racial cliché in an innovative dance, which helps to shape her into a black icon. His whole career is in keeping with it. Her performances induce pride for her skin color, but also refusal to be locked into the monolithic idea of a black culture. Josephine Baker singing The little Tonkinoise and dance charleston is exotic and French, colonial and American, avant-garde and international. She is the figurehead of the emergence of the jazz scene in France, one of the first popular music whose reach can claim to be global.

“Intersectional before the hour”, Joséphine Baker is also transnational. Its modernity lies in its way of abolishing borders, of using and then freeing itself from institutional tutelage. More than an activist inhabited by a particular ideology, she is an independent activist. Its causes correspond to its experience – it is, for example, more Gaullian than Gaullist. She advocates a multiculturalism without affiliation, which she disseminates thanks to the networks offered by the practice of her art, prefiguring these Hollywood artists whose commitments try to sensitize the greatest number.

–