We’re going to bake a steak. Just in my own words: what is very important here is that you wait for the ‘singing’ of the butter. That is to say: When the tablespoon of butter has been added to the pan, the piece of meat is not added until the butter ‘sings’. Others prefer to speak of ‘muted chats’. If the butter does not come out yet, then you are about two trains early. If the butter has talked about it, you’re three planes late.

Cooking is therefore not easy. I suspected that, but after reading the very entertaining culinary roguish reportage Yes sir! by the American journalist Bill Buford, I think I would rather have put together a very expensive Swiss watch than robbed a carp of its tail in the right way.

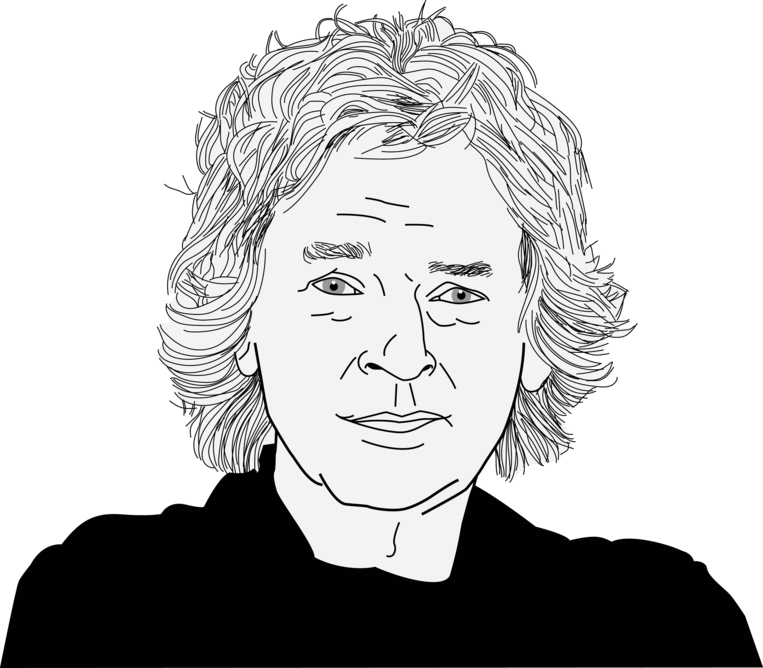

Bill Buford (1954) is not just the first. He was an American in London for a long time. From 1979 editor-in-chief of the leading literary-journalistic magazine Grant and in 1993 he became world famous with the book Between the rig, an account of his afternoons among the English football hooligans. Participatory journalism is the anvil he hits.

He later returned to America and became a fiction editor of The New Yorker, a throne. But when he had to write a report about the famous New York restaurant Babbo for that weekly, he was lost. He put on the chef’s hat uncomfortably as a curious journalist and never again as a self-proclaimed master chef in training. So it happened that the great Bill Buford was under the discipline of Italian chef Mario Batali his magazine The New Yorker Said goodbye and went to one of Babbo’s kitchen tables without murmuring radishes and carrots for a year. Unremunerated. Meanwhile spying for the soul of the kitchen in general and that of ravioli in particular. He wrote about this Hitte (2006).

Now there is the sequel: Yes sir! Not half done here either, by the way. With his wife and twins of 3 years old, Bill moves for five years from New York to the French culinary capital Lyon, where father, as a chef’s buddy, must and will discover the secrets of French cuisine.

Bill is maniakaal lover on his own eagerness to learn and certainly not the sunshine in the house. But that’s not a bad thing at all, because there is no one in the farthest reaches of this book who has ever lovingly caressed a dog or been smiling in a photograph. In Lyon, we understand, with every set of pans there is a joyless mouthpiece to see if the omelette has the standard yellow color.

And the poor kitchen brigade – call sign: whores – knows no better on a good day than that Michelin stars can only shine when the plates are often prepared spinning with fear. Yes sir! once again a wonder that these often nervous kitchens conjure up the most refined dishes, but hey, Miles Davis’s tender trumpet solos were also blown by a stinky, shit-boring lady’s swatter and everyone agrees that the vulgar, screaming Gordon Ramsey ‘the most tender fucking Beef Wellington’ in the world.

All this aside. At the table! We would almost forget why we are together. One fine afternoon Bill Buford is served a dish by chef Marc Veyrat. Veyrat: big black hat, ditto sunglasses, also in the kitchen. He is called the craziest chef in France.

He comes to the table with two doughy green balls and a kettle of liquid nitrogen. Bill Buford has to close his eyes and Veyrat says, “You are walking through the woods, the leaves brushing your face when you suddenly stumble over a tree root and fall face-to-face in the mud.” Then he asks his guest to open his mouth and puts an earth bomb boiled in nitrogen on his tongue. A taste explosion follows, I quote Bill of course, “of all the forest experiences you have ever had in your life.”

From singing butter to a mouthful of heavenly mud. It doesn’t just happen. It has its price. Yes sir! is actually mainly an insane portrait of the altar on which the guild is willing to sacrifice almost anything: the divine food.

Bill Buford, Oui, Chef! Adventures in Lyon: in search of the secret of French cuisine. Meulenhoff, 463 p., 24.99 euros. Translated from English by Lidwien Biekmann and Koos Mebius.

–