–

By GLORIA CHÁVEZ VÁSQUEZ

In New York, the writer Reinaldo Arenas was a voluntary recluse. Surrounded by friends who admired and flattered him, and countless enemies, many of them agents of the Fidel Castro regime, who, crouched, promoted Marxist ideology and reminded him with subtle but insidious threats that, although he had escaped from the island, he was not totally safe. But Reinaldo was never silent and he confronted them whenever he could: in conferences, articles and interviews. At the same time he was building his work.

His social life, like his schedule, was rationed by the discipline and haste to write the work he had to produce. before dark. Its popularity in the Big Apple was due, initially, to the curiosity it aroused in intellectual circles and the rumor that the most relevant Cuban writer of the century had escaped from the communist island. As a breast deja in the Pasternak style, his writings had been smuggled and published in France, to the eternal chagrin of Castroism. After his odyssey in the Mariel exodus and a short stay in Miami, Reinaldo had decided on the great metropolis, because, like John Lennon, he believed it was where was the action. Probably the place where your sexual identity enjoyed the greatest freedom.

The Mariel exodus (1980) hit New York and other North American cities like a huge meteorite. The different communities turned their assistance to the new victims. To everyone’s surprise, marielitos they brought among them a disturbing and dysfunctional element. Many of his benefactors were victims of his protégés. Over time, a high percentage of them ended up in jail or the morgue.

I obtained the detail of the newspaper production produced by a group of intellectuals left by El Mariel from two exiled artists, Ernesto Briel and Jesús Selgas, personal friends of Arenas. In this way they hoped to differentiate themselves from human tsunami (125,000), much of which came from prisons and asylums, and which the opportunist Castro regime had infiltrated, to discredit the Cuban colony in the United States.

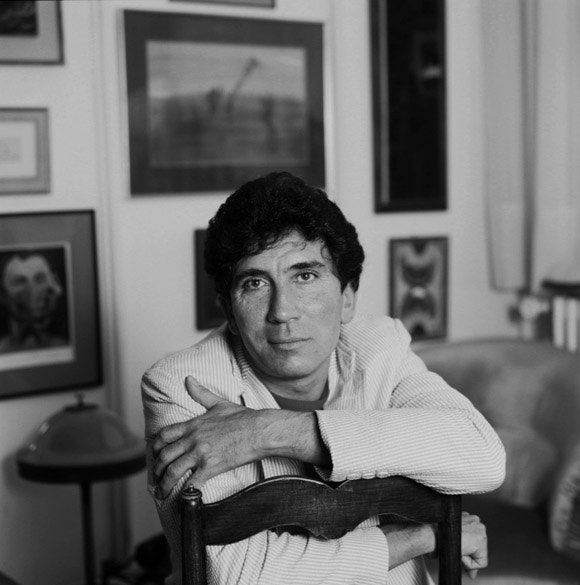

I met Reinaldo on several occasions: at the theater, where Florencio García Cisneros, editor of Art News, He introduced him as the great writer that he was; then during the Latin American Book Fair that sponsored the University of New York and where we both exhibited our books. By then, writers were being discriminated against, privileging those committed to the left. A mutual friend, Oriol Contreras, officially introduced us and shortly we held rare but interesting gatherings, like the outcasts we were, in the city of skyscrapers. As a good Caribbean, Reinaldo was a loving man; of pleasant voice and pleasant presence. The most remarkable thing about him, and at first glance, was his thick hair and his eyes with an intense, somewhat withdrawn look. On several occasions he gave me and autographed some of his books and it was in this way that we arranged articles and interviews for the newspaper and the publications for which I wrote.

When I sent the first interview to Umberto Senegal, poet and editor of Kanora, one of the literary magazines circulating in Colombia at the time, I also sent him copies of The central Y Arthur, the brightest star. Senegal recognized its literary value, and immediately began correspondence with Arenas. The poet and professor of literature Carlos A. Castrillón, who had read about the writer in Ángel Rama’s article “Reinaldo Arenas al ostracismo,” realized the relevance of the writer. He searched and found some stories by Arenas that were circulating in anthologies.

In 1986, Senegal published an essay on The central, which ended up seducing the reader in Castrillón and since 1989, when he began his teaching, he included it along with Leper colony in his seminars on Latin American poetry. In 1991, after the death of the writer, as a result of the article “The Hells of Reinaldo Arenas”, by Eduardo Márceles, published in the Magazine from The viewerCastrillón understood the value of Arenas’s work, beyond the political issue. Senegal provided him with the initial books, and the following year, on a trip to Bogotá, he obtained the others. From then on he read the complete work of Arenas. At that time, Castrillón was studying for a postgraduate degree and decided that his thesis would be on The amazing world; in the process he wrote several essays about the author, one of which was published in the magazine The nut (1992), from New York, and another in Alba of America (1997), from California. The latter, entitled “The hallucinatory humor of Reinaldo Arenas.” The articles were widely distributed and are cited in many publications and research; they are also reproduced on various web sites.

While Carlos Castrillón was busy studying Arenas’ work in depth, there was little documentation and few of his books were circulating. In 1993 Castrillón finished his thesis, which was published by the University of Caldas (1998) with the title of The rewriting of history: about El Mundo Alucinante, an overview of Arenas’ work. He later published Repeat words, in which he concentrated in his analysis.

Today, Castrillón, a professor at the University of Quindío and an expert in the work of Arenas, is part of the research circuit in Masters and Doctorates that study the writer’s work. Among the theses directed by him are titles such as Cynicism in the work of Arenas and one of the most recent: Freedom to live manifesting.

By the time the movie was released Before dark in Bogotá (2001), Time posted a review titled In the footsteps of Reinaldo Arenas. Its author, Jimmy Arias, commented that it was worth “dwelling on the figure of the man of letters, beyond his sexual life and his political position.” And he added: “Some of his works bear that stigma of an exiled and oppressed man, such as The central, which revolves around his stay in one of the forced labor camps for Castro’s prisoners, in which he was confined ”.

Colombian writers such as Juan Gustavo Cobo Borda consider Arenas a great novelist. RH Moreno Durán, who met Reinaldo in the 1980s, when he was working with the Montesinos publishing house in Barcelona (Spain), (the same one that published his first book, The amazing world and one of his last, Arturo, the brightest star) affirms that “The best of his literary work is without a doubt The palace of the very white skunks Y The amazing world”. Moreno Durán is convinced that the latter “is one of the great novels of our generation.”

Another Colombian who had the opportunity to get to know Arenas intimately in New York, and who has become one of the main promoters of his work, is Jaime Manrique from Barranquilla. Manrique dedicated a chapter of his book to him Eminent Fags. In your article The rebirth of Reinaldo Arenas published in The Village Voice (2000), Manrique cites Reinaldo’s response to his question as to why, being so broken in health, he wrote so eagerly. According to the Colombian writer, Arenas replied that writing was “his last revenge.”

* This article was originally published on the ZoePost portal (www.zoepost.com), founded and directed by the writer Zoé Valdéz. It is published with the permission of the medium and the author, Gloria Chávez Vásquez.

** Gloria Chávez Vásquez is Colombian, short story writer, novelist and journalist.