The previous experiences and failures in the development of artificial blood underline how difficult it is to imitate or replace our blood. Despite all the advances in medicine and biotechnology, this ingenious patent from nature has so far been indispensable. This is one of the reasons why some research teams are now looking for another way of at least reducing the shortage of suitable donor blood.

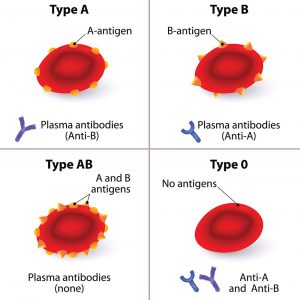

Your starting point is the fact that not every blood donation is suitable for every recipient. A transfusion is only possible without complications if the blood group is correct and the red blood cells have the right molecules on their surface. It is even better, however, if these identification markers are completely absent, because then the recipient’s immune system does not even recognize the transfused blood as foreign.

Sugar scissors against blood group antigens

This is where scientists come in to create a universal donor blood: They are looking for methods with which the disruptive sugars and protein attachments of the red blood cells can be removed after the donation. As early as 2018, researchers working with Stephen Withers from the University of British Columbia discovered some enzymes in an intestinal bacterium that specifically cut off the blood group antigens A and B.

“If you remove these antigens, which are just simple sugars, then you can turn group A or B blood into group zero,” explains Withers. This would mean that at least in the AB0 system, donor blood would be universally valid. In 2019, researchers from the same university identified two more enzymes that work even more efficiently. However: Whether this “conversion” of donated blood will work in practice and whether the effort would be financially worthwhile is still open.

A magic hat for the Rh factor

One step further is a research team that does not focus on the AB0 system, but on the Rh factor. This also restricts the use of donated blood. People with a negative Rh factor are only allowed to get RH-negative blood. However, this is relatively scarce in Germany because only around 15 percent of the population are Rh-negative.

Yueqi Zhao from Zhejiang University in Hangzhou and his team have therefore developed a method by which the Rhesus factor on the surface of the blood cells is masked. To do this, they use a special hydrogel that covers the Rhesus factor antigens like a “magic hat” and thus shields them from the immune system.

“The new technology makes it possible for the first time to transfer modified RhD-positive blood cells to RhD-negative recipients without causing an immune reaction,” the researchers explain. In tests with mice and rabbits, a transfusion with this “masked” blood has already been shown to be tolerable. The rodents showed no immune reaction after the transfusion and remained physically healthy.

However: This process is also complex and has to be further optimized for practical use. It will therefore take some time before donor blood can actually be routinely converted into universally usable blood.

–