This has led to the opposite problems of flooding and soggy soils unsuitable for planting or other fieldwork.

So far though, corn planting, which happens first, is moving at a normal pace. Reports are that over half of the intended corn acres have been planted so far in Rio Grande do Sul, and 82% in Parana. Both are near the average pace.

The other concern would be for wheat, where harvest continues in Parana and is starting up in Rio Grande do Sul. Winter wheat harvest is typically followed up with increased soybean planting in Rio Grande do Sul. With the wet weather continuing to pound the region, fieldwork may be delayed and wheat could see damage to some degree. Producers seem to be unfazed by the heavy rain thus far, but how long can that continue?

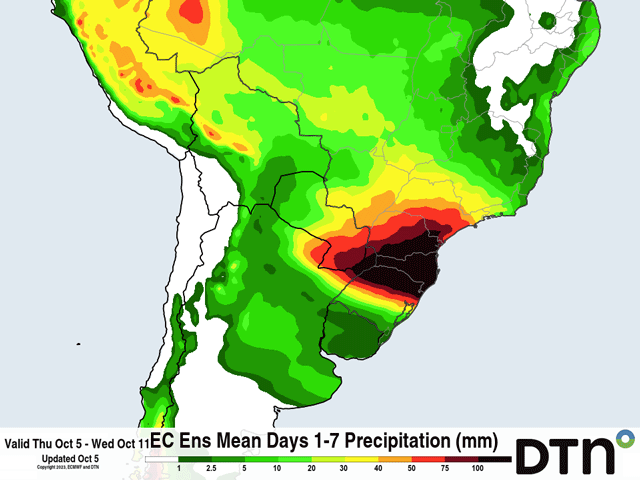

A front is currently in the region and forecast to produce widespread heavy amounts of 50-100 mm (about 2 to 4 inches) through Oct. 8. The front that moves through Argentina Oct. 10-11 settles into southern Brazil Oct. 11-13 with more heavy rain potential, probably another 20-40 mm (0.8 to 1.6 inches). That is significantly above normal, and compounds the wet weather seen over more than two months, making it more difficult to get into the fields and causing possible flood damage to wheat and the need to replant corn or soybeans.

Farther north in central Brazil, wet season showers have begun, but have not been as heavy as is typical for early October. That is set to continue for the next week as well. There will be some ancillary benefit to having fronts over southern Brazil. Occasional increases in shower intensity and coverage could make up for the lighter forecast overall. The states of Mato Grosso do Sul and Sao Paulo are likely to benefit more than the bigger states of Mato Grosso, Goias, and Minas Gerais, but the wet season showers are there and as long as they continue, producers will plant.

Models are putting down less precipitation in central Brazil through the end of October as this pattern continues with seemingly no end in sight. Though below normal, precipitation of even half of the normal amount is still good enough to get the soybean crop started. The danger then is that heat over some of the drier areas would lead to increased stress and moisture losses, without being able to build subsoil moisture for developing beans.

That could also bleed into the safrinha (second-season) corn crop, which is normally planted in late January and February. A more limited supply of subsoil moisture would be difficult for safrinha corn to produce up to its potential when the wet season rains eventually shut down.

Farther south, with dryness issues forecast to continue in Argentina, it puts yet another crop year at risk of poorer production. In southern Brazil, the soil moisture is more than enough for sustaining good crops, but is it too much? Will there be more flood damage to come? All questions whose answers will have significant implications for total production for the world’s corn and soybeans.

To find more international weather conditions and your local forecast from DTN, visit

John Baranick can be reached at john.baranick@dtn.com

(c) Copyright 2023 DTN, LLC. All rights reserved.

2023-10-05 16:21:00

#South #Americas #Stagnant #Weather #Pattern #Leads #Heavy #Rain #Southern #Brazil