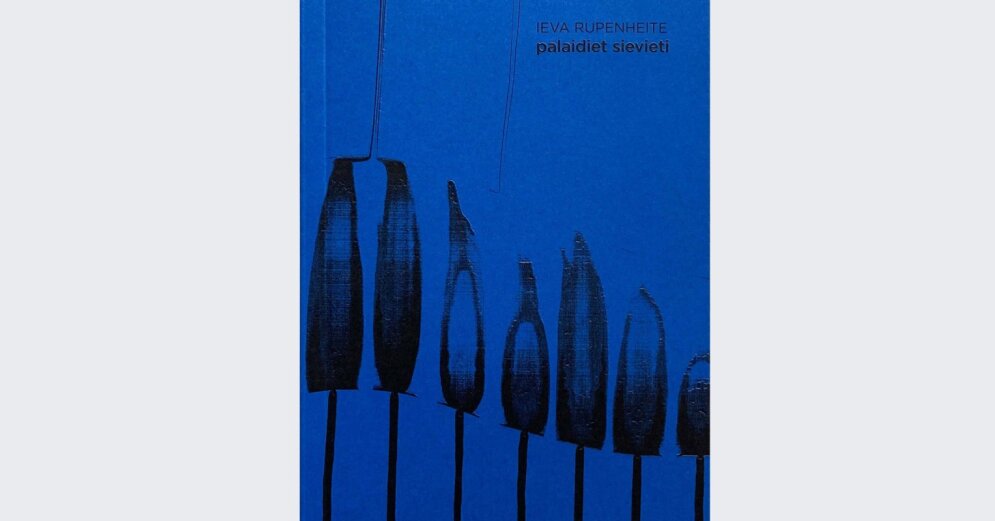

Ieva Rupenheite seems to be one of those poets who writes one book all her life. The names change – “underline” (2001), “black beads” (2007), “do not pass” (2014) and the latest “run a woman” (2021) – but the poetics and form remain.

–

–

Content will continue after the ad

Advertising

–

In the case of Rupenheit, this aspect does not necessarily mean a lack of imagination. Although the poems from collection to collection are mostly short and without punctuation, although the poetess does not significantly break her style, her short-sighted view of reality and language plasticity makes each work a special artistic event. Rupenheite’s texts embody the principle of “less is more”, drawing the reader’s attention to those volatile moments in life that are difficult to see without poetry. They are somewhere between imagination and reality, between heart and mind, and do not give peace until they are expressed in concrete and tangible images. Such Rupenheite’s texts remain true to an important ideal of poetry: being short and without punctuation, they show us language in a pure way.

As in previous works, the new book “Run a Woman” is dominated by a focus on detail – it is always taken from everyday life and, although it never loses its original context, that is, it becomes unreal, something happens with it. But what? A comparison with the collage technique could be useful here. This form, popular in the art of modernism and postmodernism, makes it possible to connect details whose connection is not self-evident. Thanks to the unusual combination, each detail of the collage acquires a new association. Thus, for example, Rupenheite connects flies and skates with a rapid shift from one element to another: “flies fly fast / who will buy them silver skates in the winter” (p. 39). Or an even more radical image montage: “a thin fox looks at a seagull / far away like a kolkhoz signboard” (p. 25). The poet remains within her daily boundaries, at the same time alienating her to such an extent that interesting literature emerges from life.

Rupenheite’s original view of tangible reality goes hand in hand with following the flow of time. Together, these methods form what might be called the documentary of her poetry. Some poems begin with a specific time and place: “the end of August / baked pancakes” (p. 44); “August / you know him / herself in a summer full trolleybus” (p. 49); “I ride the bus and read Bukowski” (p. 51). Or apply familiar bodily actions: “to make love so that flies do not hear” (p. 85); “brush your teeth and get ready” (page 87). Many poems are reminiscent of quick diary entries and often end with a detail that does not go beyond the prose beginning of the text. In the case of Rupenheit, this feature helps to create an effect of credibility and the presence of the author. This is also due to the fact that the vast majority of poems are written in the present tense.

–

–

Specificity allows the author to avoid imposing a philosophical perspective, leaving such a search to us. This pancake-baking poem ends with a completely unexpected detail: “my husband’s brother is a bodyguard” (p. 44). It provides the necessary contrast for us to reflect on the contradictions of the wider reality, on the relationship between peace and unrest. However, we cannot be absolutely sure that interpretation should go in this direction. Meanwhile, for example, the poem that begins with brushing your teeth ends with the generalization: “things are treacherous / they do not let go of the human heart / an ordinary thing / is the heart” (p. 87), and this attempt to communicate human nature is different from most parts of Rupenheite’s work. What can be deduced from these passages? Rupenheit’s poetic relationship with reality is democratic throughout. She simply allows the world to happen, to leave a mark on language, no matter how funny it may be, and rarely explains its meaning. As a result, the structure of the collage has both an individual poem and the collection as a whole – “let the woman” not find a narrative, but there is life in full coverage with all its striking coincidences. The author’s attitude towards the reader is also democratic: read and think for yourself, otherwise you understand very little, rather you experience the language.

–

–

Rupenheite says in a release on the title of the collection that it “does not claim a socially critical message and has a rather remote connection with the mood of feminism”. Today, as most poems study the reflection of the material world in language without trying to generalize, there is simply not enough room for public criticism. It suits more texts – Inga Gaile’s long poems or Liana Lang’s cycles. Rupenheit’s phrase “let go of a woman” comes from a poem where its meaning is quite difficult to establish: “let go of a woman / she has been standing here for a long time / you are running / and she is no more” (p. 49). It is clear that everyday paradox is described here, but it is not possible to know why a woman disappears. On the one hand, in these lines one can read a critical view of a woman’s visibility in society – one might think that a woman is visible only when she somehow lacks (in the poem – a seat). On the other hand, the tone of the Rupenheite stock is down, so any speculation of this nature must be treated with caution.

Returning to Rupenheit’s democratic relationship with the world and the reader, such poetry is, of course, demanding in the sense that it does not allow the reader to slip into the perception of the text. The reader is involved in creating meaning and experiencing the miracle of language. At the same time, we should not think that Rupenheit’s works would require a philologically educated reader, because she is a very willing poet, revealing just enough to make us want to read further and deeper. And also to look in the library for the author’s previous collections, which together with “run a woman” form one – somewhat surreal – poetic journey through the situations of a life.

–

–

The content of the publication or any part of it is a protected copyright object within the meaning of the Copyright Law, and its use without the permission of the publisher is prohibited. Read more here. –