Reading: 4 minutes

It took three years for them to realize it. Happens. More frequently than one would think. Elements that go unnoticed suddenly take on unusual relevance.

Everything changes then. What was once a minimal sign, perhaps incidental, becomes a central piece of the framework. And from there forward.

Between 1962, the year of the first installment, and 1965, when the third film in the series was released, James Bond cars were, so to speak, one more part among many.

Neither the reasonably straightforward 1961 Sunbeam Alpine MkV, featured in “007 vs. Dr. No,” and the aristocratic aftertaste of the Bentley 4.5 Sport Tourer, seen in “From Russia with Love,” were intended to occupy a central place in the imagination of the spectators of the time.

And although for the following year, 1964, “Goldfinger” would present, thanks to a car with special attachments, a preview of what would be the final turn in the next installment.

–

It is from 1965 that nothing was the same again. Bond’s cars would mark each of his tapes. Fenders spreading, blades sticking out of wheel nuts, hidden machine guns.

Starting with “Thunderball”, the cars of 007 would also mean, in the imagination of the general public, reliable samples of the marvels of technology, the accessories, putting technology at the service (the car itself), putting it at the service of good (Bond).

It is possible that walking is mythologically the most trivial gesture and therefore the most human, he writes Roland Barthes, a few years before the Bond movies began to appear.

With an illustrious idea of the iconic place that the automobile would have for the modern spirit of the 20th century, he asserts Barthes in his Mythologies: “Every dream, every ideal image, every social promotion, first suppress the legs … for the car.”

Machine among machines, the automobile reappears —in other words, it has never gone— from modernity to the digital century, ours, with a promise that, following the metaphor of BarthesHe now promises not only to suppress the legs, but arms and hands, too.

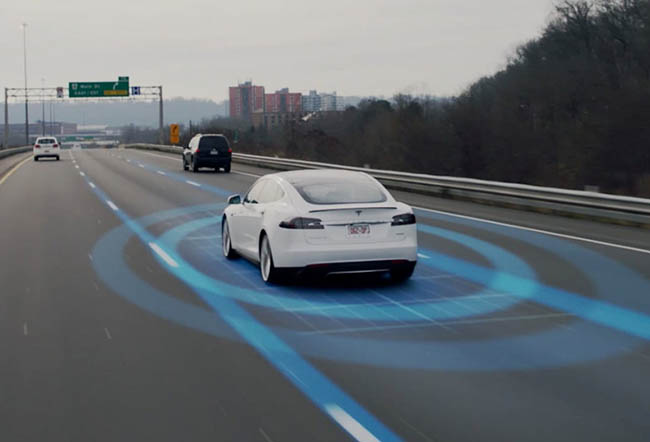

Autonomous vehicles call them the new era. Cars that do not require a driver. Or they free him, he points out, from the annoying task of concentrating, having some skill or knowledge of the basic rules of the road.

–

From environmentally friendly electric cars, whose exponential multiplication can be taken for granted in less than a decade, to autonomous vehicles, there is, however, an additional qualitative leap.

This is not just an issue that concerns the still very powerful and globally omnipresent auto industry and its endless rearrangements and mergers, what is at stake today represents more than just the entry of new players.

Already in some way, or many, the unconventional profile of the bets of Elon Musk and his unusual forays, both in sponsoring space trips and buying billions in bitcoins, had removed the representation of the “automaker.”

What will the car of the future be like? He wondered recently Marc Hijink. Question that could well be reversed, What is the future of the car ?, to follow the course of what this well-known Dutch technology analyst raises.

Between games, and no, Hijink launches: “Will it be an iPhone on wheels?”, he writes about the rumors of negotiations between Apple and the Korean Hynduai, to complete the joke by questioning: “Or could it be that we can pay for our autonomous Tesla with bitcoins?”.

The mere fact that by 2030, the automotive industry will spend 221 billion dollars, double what it spent in 2018, just on chips for its units, gives a clear idea of the way in which the production of automobiles is intertwined and the digital technology sector.

–

Touch screens, sensors, softwares, the multi-cited chips or semiconductors, today constitute the central nucleus of what we once understood as a machine powered by an internal combustion engine.

It is unclear whether Apple will finally finalize its I-Car or not. But of what there is no doubt, is that the emporium founded by Jobs is closer to launching a car than Ford is a smartphone.

It is quite curious to remember, in that sense, that of the many implements that were devised for that legendary 1964 Aston Martin DB5 that Sean Connery, unmatched James Bond, drove in “Thunderball”, few really worked.

The important thing then, however, was not that, for example, the tracking device, ancestor of our current geolocators, worked, but the very idea that it was possible.

Forty years, and little more, in 2006, Bond recovered and returned to handle that (now) old DB5 in “Casino Royale”. It is the future reinventing the past. Or, if you prefer, the past reaching the future by car.

Because there is no doubt that the promised flying cars that would populate the decades of the XXI century, according to the visionaries of the XX, are becoming, more and more, in the gadget most expensive digital on the market.

Siri handles.

You may also like: Curiosity, perseverance, creativity; navigate an uncertain century.

<!–

–>

–