Harvard John A. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences (SEAS) researchers have developed a quick and inexpensive way to test liquids for an omnipresent family of chemical compounds known as amphiphiles, used to detect diseases such as tuberculosis and cancer. in the first stage and detection of toxins in pharmaceuticals, food, medical devices and water supplies.

Today’s gold standard for testing for endotoxins, a common type of amphiphorus that contaminates water and can cause severe disease and death, requires the use of compounds found only in horseshoe crab blood, making the expensive and unsustainable method. The economic alternatives are nowhere near sensitive enough to detect amphiphiles in significant quantities.

The new test, developed by Joanna Aizenberg, Amy Smith Berylson Professor of Materials Science and Professor of Chemistry and Chemical Biology at SEAS, and Xiaoguang Wang, former postdoctoral researcher in Aizenberg’s laboratory and now assistant professor of chemical and biomolecular engineering in Ohio State University uses rolling droplets on microstructured surfaces to detect amphiphiles at ultra-low concentrations.

The research team demonstrated the technique for detecting pathogenic amphiphilic endotoxins in water, compounds that can be toxic even at extremely low concentrations.

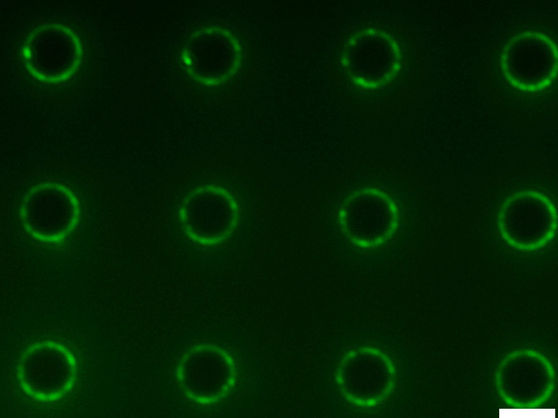

The microstructured surface consists of thousands of circular micro-pillars that are evenly coated with self-assembled long-tail molecules, creating a smooth, friction-free interface except for the edges of the micro-pillar. There are gaps in the lining here, like molecular holes. If a drop rolls on the surface and has no amphiphilic molecules, it hits a hole and stops because it cannot overcome the friction of the messy edge.

However, a drop with a higher content of amphiphilic molecules continues to roll because the amphiphilic molecules combine with the long-tailed molecules and fill the gaps in the surface, like pavement smoothing the surface of a road. In the case of endotoxins, the amphiphilic molecules that settle on the surface combine with other amphiphilic molecules in the droplet, forming increasingly larger compounds that eventually slow down and block the droplet. The point where the drop stops on the surface provides information on how many holes it has patched and thus on the concentration of amphiphiles.

“Our surfaces provide a fast, portable method for detecting amphiphores in droplets that can be seen with the naked eye,” says Aizenberg. “There are no other methods that can detect concentrations as low as we see in our tests without using expensive or complicated equipment.

The researchers also developed a model to predict how different amphiphilic compounds at different concentrations would interact with the textured surface. By changing the size, shape, spacing between columns and the molecular coating, the surface can be adjusted to detect specific types of amphiphiles at specific concentrations.

“Our method is generally applicable to any type of amphiphile,” says Wang. “With this general method, we can already detect endotoxins at levels relevant to water quality testing, but the test can be further optimized to detect even lower levels.”