With its announcement Friday that it would move its headquarters from California to Texas, Chevron Corp. became perhaps one of the latest dinosaurs to fall into the tar pit, a symbol of California’s monumental transition from a manufacturing and production state to the brave new world of services.

In the popular imagination, California has long been regarded as Hollywood, with its sunshine and beaches attracting millions of new residents and building its sprawling cities. But in reality, for decades, the great magnet for growth was the production of goods: think aerospace, oil and agriculture.

The transition away from manufacturing has been underway for decades, with examples including Silicon Valley, which generates the ideas for high-tech devices but leaves the actual production to others, overseas, and the vast ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach, which unload the huge flow of manufactured goods from abroad.

Now it’s Chevron’s turn.

The oil giant was founded in California 145 years ago at the dawn of an era in which the state became one of the world’s leading suppliers of petroleum and its derivatives.

But in recent years, the company has clashed with Sacramento over energy and climate policies, which now take precedence over manufacturing for many. On Friday, the company announced it will move its headquarters from the Bay Area to Houston.

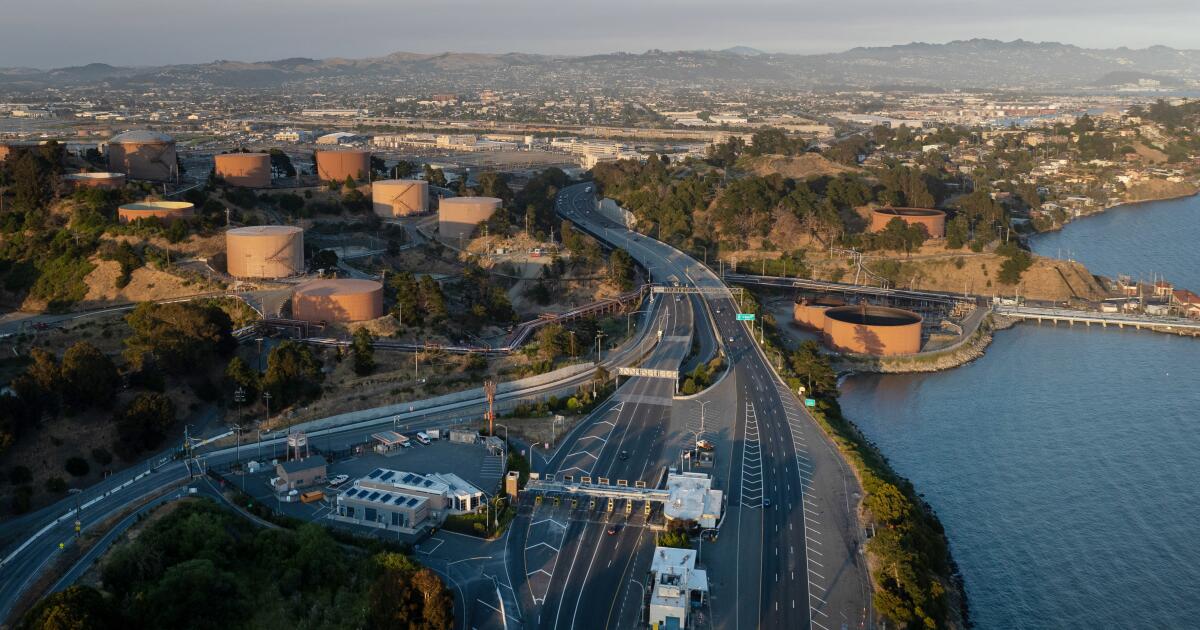

The move is part of a long and steady exodus not only of Chevron’s operations but of the broader oil industry in California, which at its peak early last century produced more than a fifth of the world’s total oil.

While California remains the seventh-largest oil producer among the 50 states, its crude output has been falling since the mid-1980s and is now down to only about 2% of the U.S. total, according to the latest data from the U.S. Energy Information Administration.

The reduction reflects the extent to which the state has staked its fortunes on moving away from fossil fuels toward renewable forms of energy, and in particular away from gasoline-powered cars to become the center of the electric vehicle industry.

“Oil and gas have shaped California, but it has been in tremendous decline,” said Andreas Michael, an adjunct professor of petroleum engineering at the University of North Dakota. Chevron’s exit from the state, he said, “is a milestone in that decline, and it’s very sad to see.”

Sarah Elkind, a history professor at San Diego State University who has documented the profound impact of oil production on people’s health and industry at large in Los Angeles, wondered aloud whether Chevron was abandoning California to escape regulatory scrutiny.

“It is unfortunate that corporations relocate their workers to places that have fewer environmental regulations instead of working in ways that lead to healthy and vibrant communities,” he said.

Chevron, the second-largest U.S. oil company based in San Ramon, did not respond to interview requests Friday. In a statement, the company said the move to Texas would allow it to “co-locate with other senior leaders and enable better collaboration and engagement with executives, employees and business partners.”

Chevron has been scaling back its presence in the Bay Area. It moved a subsidiary, Chevron Energy Technology, to Texas last decade, and two years ago it sold its San Ramon campus to move jobs to Houston. The company already has about 7,000 employees in the Houston area.

Chevron has about 2,000 employees in San Ramon. This is the latest high-profile departure of a California company to another state.

Elon Musk recently said he is moving his companies SpaceX and X from California to Texas, and over the past decade there have been many other California companies in tech and other industries fleeing the state, with many attributing this to the state’s high operating costs and other policies they feel are not business-friendly.

Last fall, California’s attorney general sued Chevron and other major oil companies, alleging that their production and refining operations had caused billions of dollars in damages and that they had misled the public about the risks of fossil fuels in global warming.

Chevron Chief Executive Mike Wirth has rejected the lawsuit and California’s approach to climate change, saying global warming is a global problem and piecemeal legal action is not helpful.

Gov. Gavin Newsom’s office downplayed news of Chevron’s relocation on Friday, highlighting growth and opportunities in clean energy for California, which he said already has six times as many jobs as fossil fuel jobs.

“This announcement is the logical culmination of a long process that Chevron has repeatedly announced,” said Alex Stack, spokesman for the governor’s office. “We are proud of California’s place as a leading creator of clean energy jobs, a critical part of our diverse, innovative and vibrant economy.”

Wirth and Chevron Vice Chairman Mark Nelson will move to Houston before the end of the year. “The relocation will have minimal immediate impact on the remaining employees currently located in San Ramon,” Chevron said in its statement.

Some operations will remain in San Ramon — along with “hundreds of employees,” Wirth told CNBC on Friday — but the company said it expects all corporate functions to move to Houston within the next five years.

“We have a history we can be proud of in California,” Wirth said, noting that the company began in 1879 in the Pico Canyon oil field just west of Newhall, the site of the state’s first major oil flow three years earlier. But he said Houston is the epicenter of the industry and where Chevron’s suppliers, vendors and other key partners are located.

Chevron began as Pacific Coast Oil Co., incorporated in 1879 in San Francisco, and was later long known as Standard Oil of California. Along with other companies, it capitalized on the Los Angeles drilling boom of the early 20th century, when large oil fields were discovered in places like Long Beach and Santa Fe Springs, spurring industrial development in the region but also raising growing concerns about its impact, especially in working-class neighborhoods, with uncontrolled wells, fires, oil spills and noisy diesel pumps, Elkind said. By the 1920s, 20 percent of the oil produced in the U.S. came from Los Angeles County.

California’s relationship with the oil and gas sector survived well into the 1960s, but the Santa Barbara oil spill in the late 1960s helped spur a massive environmental movement, said Michael, the University of North Dakota oil expert. With the state’s aggressive pursuit of zero-carbon policies, crude production has fallen to less than 300,000 barrels a day, about a quarter of what it was in the mid-1980s.

“And I don’t think we’ve hit bottom yet,” said Uduak-Joe Ntuk, an industry expert who until this year monitored oil fields for the California Department of Conservation’s energy management division. There are still thousands of oil wells in Los Angeles County alone. “We have billions of barrels of recoverable oil in California, but they’re in the ground.”