Since 2015, Brazil has experienced frequent declines in immunization coverage for children and adolescents. In 2022, the scale of the problem has become a more evident concern, especially after the WHO (World Health Organization) listed the country among those at greatest risk for the return of polio and Fiocruz (Osvaldo Cruz Foundation) warned that the the only immunizer with ideal vaccine coverage around here is BCGagainst tuberculosis.

However, knowledge of the problem hasn’t actually increased the percentage of Brazilians who are fully vaccinated.

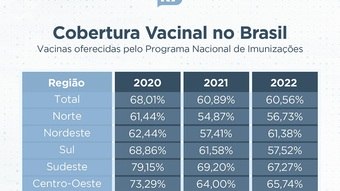

According to data from DataSUS (Department of Informatics of the Unified Health System), as of 20 December 2022, 60.56% of the population had completed the vaccination calendar with all the vaccinations offered by the PNI (National Immunization Program).

In 2019, this index was 60.89%. The justification for reaching the lowest rates in history was the pandemic and social isolation.

However, since March of this year, the lockdown rules have been relaxed and, for now, the number remains practically at the same level as in 2019.

The PNI offers vaccines against 20 diseases in 38,000 vaccination rooms across the country. For the experts heard from R7the reasons for this decline in coverage are not limited to the pandemic.

“It was not only the pandemic that was responsible for the decline in vaccination coverage. We’ve also had misinformation, which has led to questions about the importance and safety of vaccines. The lack of campaigns promoted by health managers also has an influence”, says the infectious disease specialist Raquel Stucchi, professor at Unicamp (State University of Campinas).

For Renato Kfouri, director of SBIm (Brazilian Society of Vaccinations) and SBP (Brazilian Society of Pediatrics), the size of the country means that the causes of the problem are different.

“The reasons why someone is not vaccinated in a large metropolis are not the same as for someone from the riverine population of the Amazon or the interior of Piauí. The reasons are various: from access problems, difficulties in opening hours, problems with transport costs, shortages [de vacinas]fake news that says vaccines are bad.

The number considered ideal by the Ministry of Health and the WHO varies according to each vaccine, but a coverage of more than 85% is expected to prevent the circulation of diseases.

Brazil has been considered a model of vaccination in the world for more than a decade and doctors believe that it is possible to return to the level lost in recent years.

“Recovery is no easy task, no doubt, but it requires a lot of effort and the first steps need to be taken,” warns Kfouri.

“It must be a priority job for the next government, to restore the population’s confidence in vaccination, in our National Immunization Program. With that, we will once again be an example of vaccination adherence to the whole world, as we once were,” adds Raquel.

Among the actions aimed at reversing this situation in 2023 are awareness and communication campaigns by health authorities, investments in training, distribution and personnel to work in alternative hours and the creation of vaccination campaigns.

For the infectious disease specialist, campaigns should target parents and healthcare professionals. “We need to keep motivating people to get vaccinated so they don’t feel threatened. This is a big challenge and even health professionals who no longer treat these diseases, no longer deal with these cases and end up recommending them less emphatically,” Kfouri guides.

“Concern and action planning for the next government must start now. Communication must be efficient, in plain language, focusing on the benefits for the population and the importance of vaccinating everyone,” concludes Raquel.

All the effort is worth it from a human and financial point of view. According to WHO estimates for 2020, vaccines prevent four deaths worldwide every minute and generate savings of R$ 250 million per day.

Check out the 20 worst pains a human being can experience