Öland is quiet and slow when it is not season, tourist season. The narrow island lies like a long strip of land, parallel to the coast of Småland. The traffic over the bridge from Kalmar to Färjestaden is sparse.

This is how Öland is this day in 2001, when an old man steers his almost equally old American out to the disused quarry by the sea.

He brings with him the dog, a wreath of roses and a pile of old letters. He will hold a ceremony on the beach, for his own peace of mind. Then he will break the silence about what happened a long time ago, a terrible day in 1929.

He never gets that far. Up in the quarry, someone triggers a landslide of boulders. Throws stones too, to be sure to hit. The old man dies there, before he has time to break the silence.

The rumble from the beach

In the cabin, a short distance from the sea, sits Gerlof Davidsson sorting old papers. He hears the rumble, but does not make it go up. There is no longer any activity in the quarry where ölendinger has struggled and practiced stonemasonry for food for almost indefinite time.

He stops and asks the taxi driver who transports him back to Marnäshjemmet, but does nothing more until he drinks coffee with his remaining relative, Tilda Davidsson. She’s a police officer. Did she hear the rumble too?

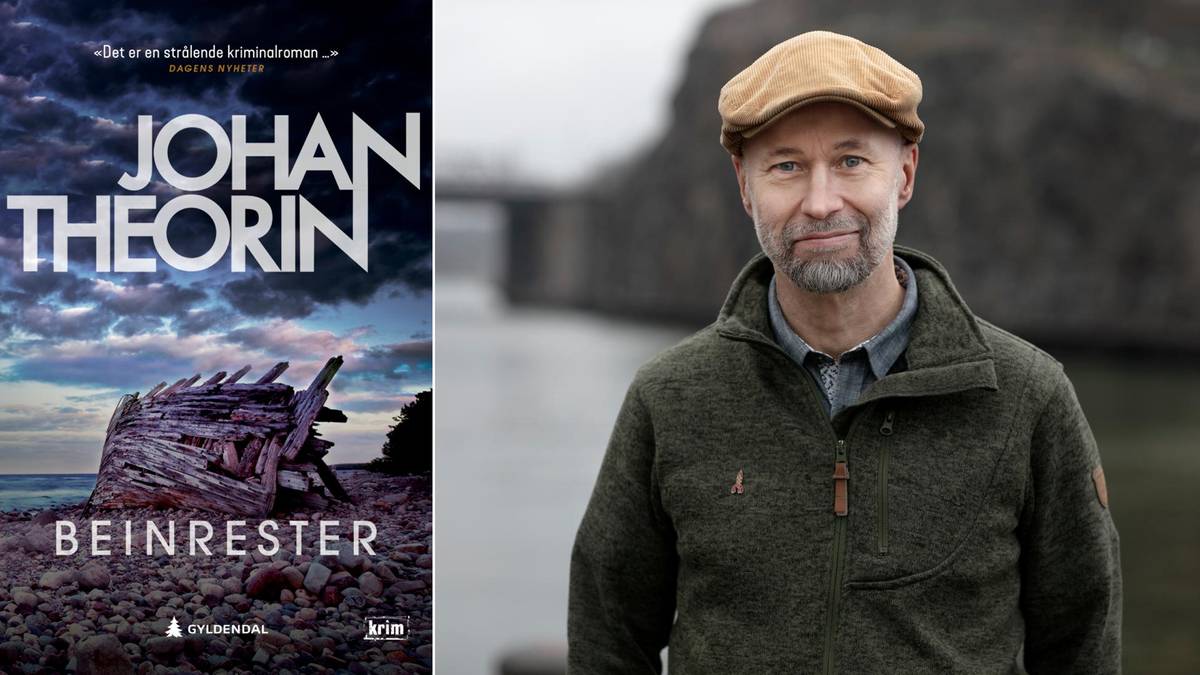

This is how we start with «Bone remains».

Gerlof, our man

I had a hope, when I was asked to read Johan Theorin’s latest book, that there would be another story about Gerlof. He and I have somehow been on first names since the first book, “Twilight Hour”, in 2008.

Gerlof is a skipper and sailor, local historical oracle and omniscient. He is a good man, eternally curious, a ruthless stabeis facing injustice, old as new, murder or disappearance. A man who thinks and talks about love and life with respect.

Simply put: I have long liked Gerlof Davidsson.

Fear and beauty

At the same time, I greatly appreciate Johan Theorin’s empathetic communication of nature, the distinctive landscape on an island that is also his own. The huge sky, low vegetation, rocks, sea and sea again.

Even better, this great nature is in Theorin’s books (and Gerlof’s memory) inextricably linked to history, lived by all the individuals and destinies that have made up the generations before.

At the risk of becoming pompous: We are talking about the beauty as well as the horror of human conditions.

So too in this new book. I have already mentioned a terrible incident in 1929, that it is connected with the man who dies on the beach, buried under boulders.

Another has suffered almost the same fate, a long time ago. There is also a direct connection to Gerlof himself, to the only boat in his possession that was lost.

Gerlof wants to make the unclear threads between then and now visible with the help of thought and memory, stubborn questioning and absent respect for danger.

The love and the letters

“Bone remains” are about all this, with a Gerlof who has to take the walker to help in daily life. But also about strong and problematic love, formulated in letters, a genre that may have died with the fall of the postal service.

And, if I have not mentioned the drama and suspense, then it is a failure that must be corrected. They are there!

It may well be that Johan Theorin’s books about Gerlof and Öland on a level or two may be similar. It has never bothered me, it comes, so to speak, from the setting itself, the local historical and personal premise on which the stories rest.

Perhaps it is also in the author’s talent that he has not been tempted to mass production. Gerlof’s universe can easily withstand five books in a decade and a half.

Then the reader can look forward to finding out if Gerlof succeeds once again in repairing some of the damage the dead have suffered, clearing out an innocent appointee and creating balance in the accounts.

And along the way, another extremely well-written book from Johan Theorin’s hand, in the safe hands of translators at Kari Bolstad.