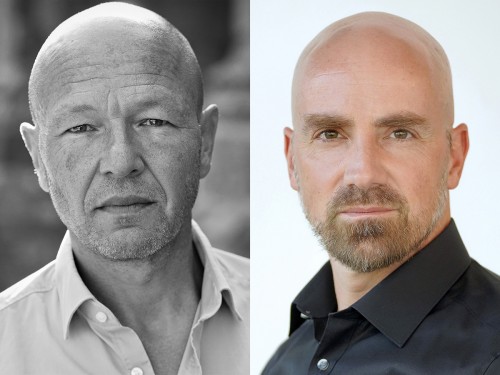

Achim Conrad and Thomas Hupfer

Photos: Press / Alexander Ourth

–

January 06, 2021

Trilogy “Auf-Brüche” about the writer Ingeborg Bachmann – premiere 12/20

Ingeborg Bachmann was the female shooting star in German-language literature after 1945 – and had to pay a high price for it. This not only included dealing with the Nazi past and the father who was a party member. Repressive social and patriarchal structures and the petty-bourgeois narrowness of Austria made it difficult for her. After Lenz and Kafka, the two actors and directors Achim Conrad and Thomas Hupfer dedicate their series Auf-Brüche to the life and work of Ingeborg Bachmann.

choices: Mr. Conrad, Mr. Hupfer, how does Bachmann fit in with Lenz and Kafka?

Achim Conrad: With regard to their unconditionality, tragedy, consistency and effect, Ingeborg Bachmann fits perfectly with Lenz and Kafka. The necessity to create something new in art, to break new ground. The tragedy: All three of them broke down a little in their lives and died relatively young. Finally, the effect: All three have been pioneering in their field, i.e. Lenz in drama, Kafka in prose and Bachmann in poetry.

What price did Bachmann have to pay for this effect in the then largely male-dominated literary business of the 1950s and 60s?

Thomas Hupfer: The price she pays is a very high one. The consistency with which she asks questions about identity, about self-positioning in the world, from ever new points of view, is what she herself once called an absolute madness. She has not allowed herself to really come to rest and to settle down, but rather complains about her lack of housing in the world. Going to extremes was definitely an imposition for some contemporaries – and it still is today. Much about Ingeborg Bachmann can be interpreted as a loss of ego: the excessive demands on oneself, the self-portrayal, the role play.

To person

Achim Conrad, born in 1965, is an actor and director, has the ensemble movingtheatre.de co-founded and has been awarded the Cologne Dance and Theater Prize several times. The actor Thomas hupfer works regularly at the cloister festival in Feuchtwangen, at the FWT in Cologne and as a speaker for the radio.

„Perceived as a diva of literature “

What roles are they?

TH: We have chosen three models for our staging: The youthful, optimistic break-up Ingeborg Bachmann, who believes she is still up to the literary world and life. Then the rather boyish writer who moves and is accepted as a female figure in a male-dominated literary world. After all, she has been perceived and described as a diva of literature.

AC: For us, the trilogy is a project that reflects the lives of the artists and their works and seeks what is today in these three artists Lenz, Kafka and Bachmann. With Lenz you have this storm and stress, with Kafka we found the natural theater of Oklahoma from “America” as a bracket. Bachmann, on the other hand, still seemed brittle to us at first. We put the poetry at the center, but for a long time it was unclear how that could be brought to the stage.

TH: The framework that we have chosen for the staging can be described with a quote from Ingeborg Bachmann: “For me, nobody has died and rarely does anyone live except on my stage of thought.” We had this image of the stage of thought from the beginning a charm because you don’t have to write a biography or dramatizations on it, but only let Bachmann’s decisive experiences, people or characters from their works appear. Together with the actress Anna Döing, we are mainly concerned with Ingeborg Bachmann’s departure.

„There are sentences by Ingeborg Bachmann that can be read as a guide to being unhappy “

Which new beginnings are important for your staging?

AC: Her confrontation with National Socialism, but also her fight against populism and conservatism, determined her life. That is one of the topics that has remained topical to this day.

TH: In her war diary she describes how she experienced this time. That she doesn’t want to go back to the bunker, but rather, if she has to die, then reading in the garden and in the sun. She refuses to let war determine her actions and thoughts. There is such an unconditionality in there again. Then she decides to set out from this little Austria into the world.

AC: Then love. This is a very important keyword in our staging. Love, that’s the hardest thing, writes Ingeborg Bachmann. Love is the greatest work of art one can imagine and only a few can. And then she says very clearly that she cannot do this work of art herself. Nevertheless, she is always looking for it, engaging in relationships. Paul Celan then becomes the love of her life, which however cannot be lived, at least not in an ordinary way. Certainly she also failed because of love because she did not succeed in accessing the simplicity that love can also be. Or maybe because of the men she has chosen.

TH: There are sentences by Ingeborg Bachmann that can be read as instructions on how to be unhappy. This includes the sentence: “You have to forbid yourself from the easy.” Paul Celan once said of her that she was “at home in the difficult”. And at the end of her poem “Explain me, love” it says: “I see the salamander / walking through every fire. / No shiver chases him and it doesn’t hurt him. ”So she has to arm herself against the injuries, especially the love.

„We focus on poetry “

What is Ingeborg Bachmann’s aesthetic departure and how does it play a role in your staging?

TH: Marcel Reich-Ranicki praises Ingeborg Bachmann for combining tradition with modern poetry in her poems. And that’s why it was so successful. That is why we put the genesis of poetry at the center. With this connection she has achieved something really great and we try to make it audible, tangible and tangible. How is poetry actually created? There are descriptions by Ingeborg Bachmann of how she began to make sentences out of scraps of music at an early age, how she lay on the embankment and let her imagination wander and then pictures came to her. Then she wrote down sentences that she didn’t understand, but that struck her as special. Or that she later wrote that the first three lines always had the whole poem.

AC: So there will be a sealing room, a work room in which she works. A space that is very artificial and abstract, but in which you can create a completely different sound quality and which enables different listening to these texts. We also looked for scenic moments that a poem really fits. Moments that the verses may not explain one to one, but in which you can feel the strong experience from which the poem breaks its path.

And how does Bachmann’s poetry help us in the presence of a pandemic?

TH: There is a point where Ingeborg Bachmann doubts the meaning and relevance of art, especially poetry, and says: A poem cannot end a war. It’s lonely and rightly no one cares. Perhaps that’s how we feel as artists at the moment. We cannot end a pandemic either. Is that why we are lonely and rightly don’t care about anyone? We hope not. Do you need a poem by Ingeborg Bachmann in times of crisis and do you need a theater evening about her? Maybe more urgent than ever.

Bachmann | D: Achim Conrad, Thomas Hupfer | Dates after announcement | Independent workshop theater | 0221 32 78 17

INTERVIEW: HANS-CHRISTOPH ZIMMERMANN

Did you like this article? As an independent and free medium, we depend on the support of our readers. If you would like to support us and our work financially with a voluntary amount, you can find out more via the button on the right.

–