It can be wrong, life. We have all experienced that. Some experience more of the wrong than others.

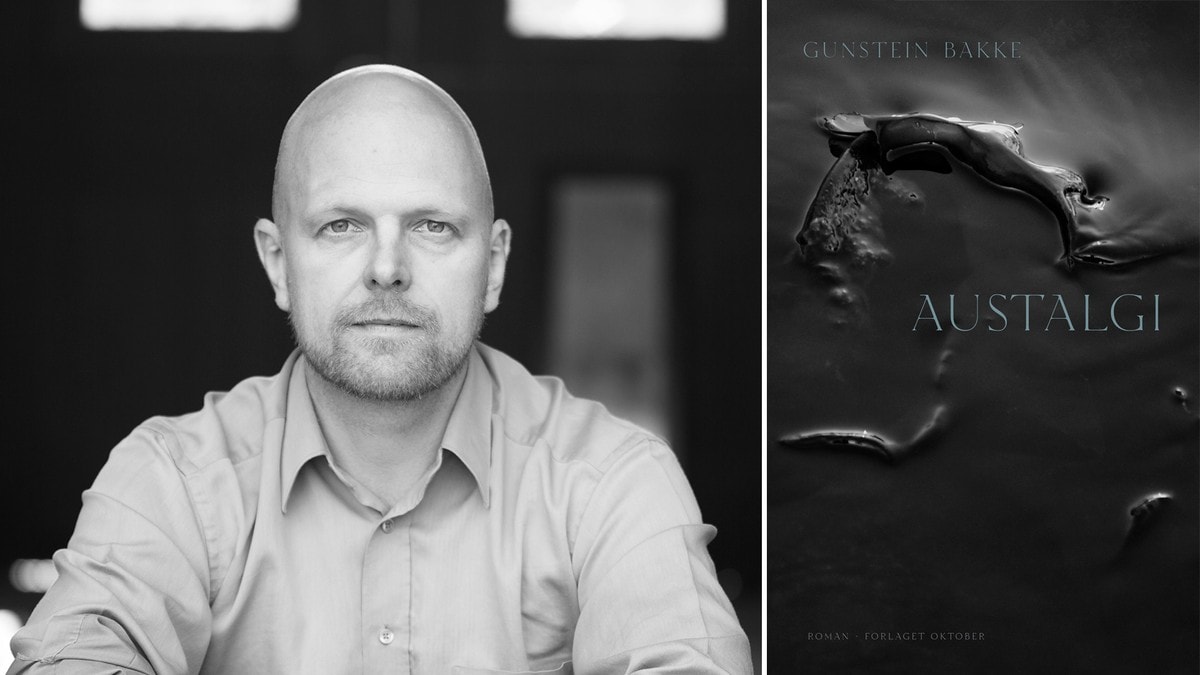

Gunstein Bakke lets his novel characters reflect on right and wrong, but they do not draw clear moral dividing lines.

The shamelessly self-righteousness makes the novel uncomfortable, but nonetheless exciting to read.

Predators and prey in the same person

If “Austalgi” evokes associations with nostalgia, there is not much rosy romanticization in this novel.

The ninety-nine-year-old Mikkel, who has taken life seriously at the expense of others, is set on fire in his own home by two of the village’s restless young people. Is it fate that punishes the ruthless? Perhaps his description of his daughter Rancine also applies to him; she is a predator and prey in one. Rancine was bullied growing up for her reading and writing difficulties; now she uses her wordless power over the elderly at the institution where she is a nursing assistant.

14-year-old Melissa is the third of these almost limitless people to populate the novel. A large number of supporting characters are also intertwined, in a story that more than epic chronology provides a sensuous entrance to the interior of some vital southerners.

Short story

The outer frame is as follows: Amanda, Mikkel’s daughter and Melissa’s mother, is going on a business trip and lets her grandchildren and grandfather take care of each other for a week. The two do not have much in common, beyond a tantalizing fascination for the differences that a span of 80 years inevitably brings to light.

Throughout the story, Mikkel’s thoughts swell. A visit to the dentist mixes with memories of pastoral moments with his numerous women. Past and present slide into each other, single moments and concrete sensory experiences make time timeless, at the same time as eternity attracts him around the next turn. Gunstein Bakke gives a credible picture of a mind in mild confusion.

The old man who is about to leave life has nothing to lose by being himself completely without shame and shame. The young person who is on the threshold of life has the fearless curiosity as a ballast. In the same way that author Ali Smith lets an old man and a teenager carry the hope of the future in their formidable

seasonal quartet

, gives Bakke life to young and old. Rancine, who is in the middle of her life, lives outside traditional social networks and is therefore also almost detached from norms and neighbors.

Once the thought of Ali Smith has surfaced, it is easy to see several commonalities: Gunstein Bakke’s subtle grip on language is reminiscent of the surplus creativity of his Scottish colleague.

Linguistic sovereignty

Bakke has shown language mastery before, not least in his previous novel,

Having

, which earned him a nomination for the Critics Award. From this year’s novel, in which he goes straight into the minds of the various characters without any introductory explanation, I could quote well-formulated considerations from almost every single page. A moment of reflection, for example, Mikkel can describe as a day «when a slightly musty, blue-shaded evening light had fallen in through the lace curtain in the kitchen». He can describe the name Agder as «lumpy, grains of sand in the ice cream, stones in the shoe (…) ». Elsewhere he writes about a «maximum normal speed».

The danger of an inventive language is that it can tip over into exteriors, in considerations of the more ragged type, as when old Mikkel no longer reaches down to his own toes and Bakke writes «When the nails became long and athlete’s foot inserted (…)».

Inside or outside

Most often, the language contributes to surprising observations. Bakke spends a lot of time describing the human body, both inside and out. Inside it is not just thoughts and feelings, it is flesh, blood, muscles and pulse. Where are the boundaries between the visible and the invisible, where are the boundaries of what one can do with another’s body? Melissa’s thoughts on what it is like to be eaten by a cannibal are almost worth the release in itself. When was the last time anyone talked about cannibals in a Norwegian novel?

The title “Austalgi” is not elaborated to a small degree, other than in small drops where especially Mikkel, but also Melissa, fantasizes about what is lost when Aust-Agder ceases to exist as its own name and county, and instead goes into the big picture, merged and more anonymous Agder. Is it possible to call yourself an Austrian? More than name and county, it is time and life itself Mikkel circles in.

Gunstein Bakke stands out from the current Norwegian trend, where cohabitation novels or young authors’ autobiographical history of formation have long been dominant. His linguistic precision elevates the novel, which more than action contains reflection on being alive.

“Austalgi” is a challenging novel about people of the usual kind, with flaws, ugly thoughts and hopes for a life where both mind and body get theirs.