“Who would want to fly on route 666?” asks art historian Kateřina Kubínová suggestively in the book accompanying the current Pilsen exhibition about the apocalypse. Although the selection of artworks dates back to the Middle Ages, it provides ample evidence that the biblical text about the end of the world still resonates even in the atheistic Western society of the 21st century.

Three sixes inspires superstitious fear because it is a number said to be attributed to the devil. More specifically, the apocalyptic beast, the antichrist, mentioned in the Revelation of St. John. The prophetic text called the Apocalypse is a powerful source of inspiration and refuge for European artists from early Christianity to the present day.

The exhibition of the West Bohemian Gallery called …And I saw a new heaven and a new earth…, which will last until March 3 in Pilsen Meat Shops, draws not only on visual arts. He also discovers an apocalyptic note in the underground music and literature of the Czech lands. Several works come from foreign creators.

The narrow entrance space is lined on both sides by 12 black and white sheets by the artist Pavel Nešleha from 1994 imitating film frames. They catch the spray of mythical horses falling at dawn, they are barely legible shadows. Their appearance becomes clearer and transforms, in the last chalk drawing of the horse only a skeleton remains. The animal invasion called The Shine and Misery of Apocalyptic Horses is introduced and concluded by a pair of colorful pastels. One bears the sign of three sixes written in Hebrew.

Nešleh’s cycle is original in that it depicts only steeds, although the Apocalypse also mentions a man in the saddle. The four horsemen bringing destruction have become one of the most frequently depicted apparition motifs, as a visitor to the show will learn.

Its first chapter is devoted to the author of the Apocalypse, John of Patmos. It follows from the oldest medieval depictions that he was mistaken for John – the apostle and evangelist. But stylistic differences between John’s Gospel and Revelation have led theologians to believe that they are two men with the same name.

On the far left is St. John on Patmos by the Porainian master from the beginning of the 16th century. | Photo: CTK

Next to the exhibited illuminated Bibles, the most prominent author at the beginning of the exhibition is Albrecht Dürer. The renowned German painter of the turn of the 15th and 16th centuries was fascinated by the Revelation of St. John and personally believed in the imminent end of the world. At the age of 26, he created a cycle of graphic illustrations of the Apocalypse, which was published as a separate volume in 1498.

Dürer’s dynamic and terrifying scenes, which interpreted and also updated the complicated prophetic text, gained considerable popularity. They were also innovative, for example among the first to combine the arrival of the four apocalyptic horsemen into one constellation. They were initially depicted separately according to Jan’s makeup.

A horseman with a bow on a white horse appears first. He is marked as the conqueror. After him comes a man with a sword on a fiery steed, who will destroy the world’s peace and bring about a great slaughter. The third rider on the black beast carries scales. It brings dearness, hunger and poverty. The last man on the blue horse is death.

Albrecht Dürer depicted the four horsemen of destruction side by side. Although he was not the first to do this, his image, or rather the entire apocalyptic cycle, inspired many others. His influence spanned centuries. He was admired, for example, by Johann Wolfgang Goethe, who praised the painter for his “vigorous and unyielding masculinity cut into wood”.

The sculptor and painter Jan Koblasa, who is no longer living today, also named Dürer as one of his three inspirations, who was widely represented at the Pilsen exhibition. His second source was a film by Ingmar Bergman The Seventh Seal from 1957, and the third, “the chaos of our Czech state – the dark, darker Jiráskova”, as Koblas’s words, relating to the then socialist reality, were recorded by the art historian Mahulena Nešlehová.

Jan Koblasa: Apocalyptic Messenger, 1985. | Photo: Vysočina regional gallery in Jihlava

Koblasa was intensely interested in the message of revelation in the 1960s. Next to ghostly graphic sheets bordering on abstraction, the exhibition presents his sculpture Apocalyptic Messenger from 1985, when he lived in German exile.

The painter Jan Konůpek also experienced a long-term obsession with the theme, whose graphics from the 20s of the last century alternate between Koblas’s works and medieval illuminations in Pilsen. They are also represented by a large two-channel projection of the monumental mural Apocalypse at Karlštejn Castle.

The projection unfolds like a gothic comic book. An apocalyptic scene appears on the left side, a label pops up on the right, for example “A woman laboring to give birth is chased by a dragon”. The text is immediately replaced by several close-ups of the given image.

The complex, elaborate Gothic work, the largest of its kind in Central Europe, will amaze. The details of the fantastic scenes full of monsters, emotions and illogical events show the great imagination and craftsmanship of the author. The Karlštejn Apocalypse is surprisingly impressive, even if it is only a projection.

The two-channel projection zooms in on the largest Central European mural Apocalypse, which is located at Karlštejn Castle. | Photo: West Bohemian Gallery in Pilsen

Contemporary art is increasing in the second half of the exhibition. Minimally muted punk music flows through the space. It is a recording of a performance by the band Umělá hómá, which in 1975 accompanied the recital of the poet and also its member Josef Vondruška. He recited a poem End of the world.

The performance of Pavel Zajíček, who performed the composition, had a similar concept Apocalyptic bird. Visitors can listen to the accompaniment by The Plastic People of the Universe in headphones. It’s an uplifting feeling to hear that rolling rock avalanche cut through by the sax while looking at the gilded monstrance and paintings of love madonnas.

Věra Nováková: After the End (Hic iacet omnipotens homo sapiens), 1952, property of the author. | Photo: West Bohemian Gallery in Pilsen

These are part of another chapter devoted to the apocalyptic “woman clothed with the sun”, unquestionably attributed to the Virgin Mary from the beginning. Unlike the beast, which, according to the authors, changed its face especially in the 16th century marked by confessional wars. They once warned of the antichrist pope, while Catholic editions, on the other hand, showed the many-headed beast, the Protestant Martin Luther. Luther’s Bible from 1522 was provided with engravings by Lucas Cranach the Elder, who thus created the canon of biblical Lutheran iconography, including the Apocalypse.

Just above the heads of the visitors to the exhibition hang white boards with verses written by well-known authors. There are poems by Ivan Martin Jirous, Sváti Karásek, Milan Knížák and JH Krchovský. A frenetic piano and the singing of Filip Topol are heard from a far corner. In addition to the lovely madonnas, the testosterone-fueled literary and artistic climate is disrupted by the hypnotically beautiful and terrifying painting After the End by the ninety-six-year-old painter Věra Nováková. She painted it in 1952, at a time when she was kicked out of the academy and, in addition to her existential concerns, was burdened by a repressive political atmosphere.

Her post-apocalyptic canvas is dark and tender at the same time. Two almost naked, bald children shine into the blackness of a broken and extinguished world. Above their heads hovers an angel with protective arms outstretched.

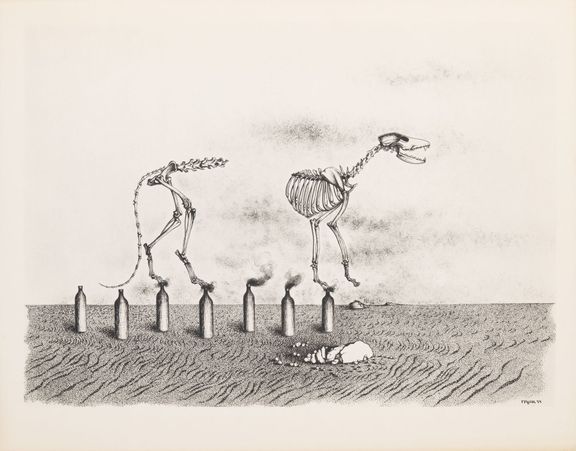

The other strong author at the end of the exhibition is the surrealist Toyen with a cycle of nine line drawings from 1944 called Hide, war.

The spiky, alienated scenes full of skeletons and eerily empty places send chills down your spine. Especially when one realizes that the unequivocally surrealist work could have gotten the artist into a lot of trouble. After all, the German occupiers declared war not only on free countries, but also on modern art. In addition, at that time, Toyen was hiding the Jewish poet Jindřich Heisler in her Žižkov apartment.

Toyen, Hide War! (cycle of nine drawings 1944), 1947, Collett. | Photo: West Bohemian Gallery in Pilsen

The majority of contemporary authors depict the apocalypse with a lowercase initial letter, i.e. as a derivative theme of the end of the world without a religious context. The paintings of Jan Vytiska, Josef Bolf or the video collage by Jakub Nepraš called the Babylonian plant speak of the emptiness inside civilization and perhaps also of the loss of self-understanding.

Only a minimum of exhibited works reflect the positive aspects of St. John’s vision. At the same time, the author of the Apocalypse does not only describe the horrors that will occur at the end of the ages. It also represents the New Jerusalem, the divine city, thus giving hope for a new, better beginning and life in paradise.

In addition to literal, especially historical illustrations, only very few artists devote themselves to a kind of divine balance and harmony in their work – among those exhibited, the painter Václav Boštík, who is no longer alive, is in first place.

Apocalypse helps though. Artists and viewers also relate to her visions in difficult times or situations, which help them reflect on difficulties and deal with them emotionally.

Eight authors, experts from the West Bohemian Gallery in Pilsen, the Institute of Art History of the Academy of Sciences and the National Gallery in Prague collaborated on the exhibition with the subtitle Apocalypse and Art in the Czech Lands.