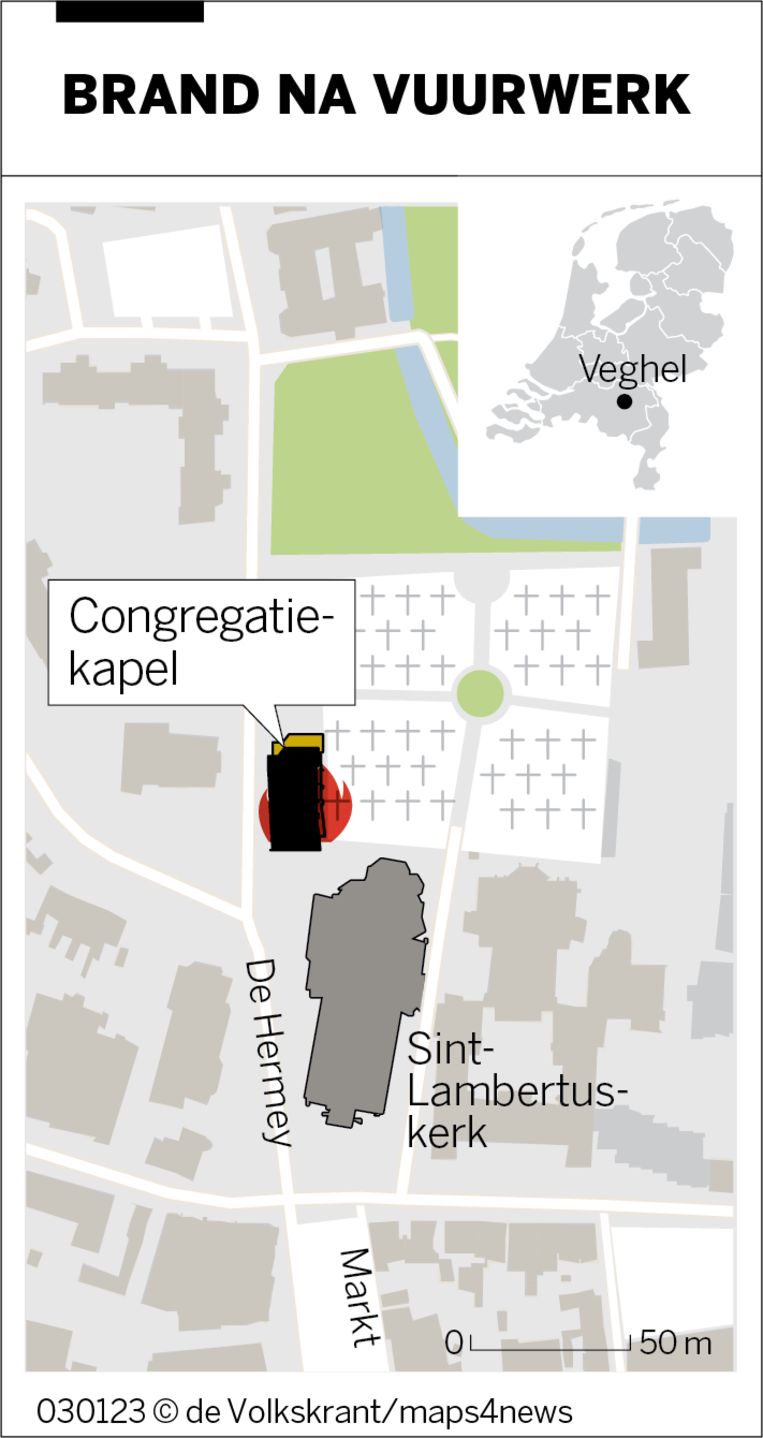

The first wind of 2023 was in a good mood for Veghel. With a north wind, one of the first great works of the architect Pierre Cuypers would almost certainly have gone up in flames. Then, shortly after midnight, the fire had leapt from the small Congregational Chapel to adjacent Sint-Lambertus. A church that was built starting in 1856, when the architect – who later became the Rijksmuseum and Amsterdam Central Station – was less than 30 years old at the start of his impressive career.

The south wind on New Year’s Eve may have been a fluke, but Veghel mourns what was lost in the flames. Because the national monument in the shadow of the mighty Lambertus may be smaller and younger, but it is also a Cuypers. Along with the cemetery and adjacent monastery, there’s a fairly unique collection of Cuypers drawings, experts say. The 1890 Congregational Chapel was a joint effort with his son Jos Cuypers.

A flash would have caused a fire in the roof, is a theory that quickly circulated in the local media. Firefighters are not commenting on the lawsuit while the investigation is still ongoing.

Thick carpet

During a walk in front of the building, chief sexton André Velthausz and local Cuypers expert Gerard van Asperen (78) are skeptical of the story that the fire may have started in the roof. Especially after watching a video, which shows how the first flames came out of the windows below. Van Asperen points to the grilles that are at hip height in the outer walls. “If something flammable gets in, the dry wood floor could catch fire,” he says. “Especially with that thick carpet on top.”

The church has been empty for some time, the carpet is a legacy of the last user: a Turkish mosque. The mosque administration acquired the building in 1980 after the library was housed there, but moved due to lack of space. To the dismay of the monument organizations, little if any maintenance has been done for decades. A few years ago the building, which had fallen into a serious state of disrepair, was sold on condition that the government restored it.

The man who took on the project is Paul Dinant, owner of the Dinant architecture firm in Amsterdam, which often restores old churches. He will transform the chapel into a nursing home for elderly people with dementia.

“The construction depended only on Monumentenzorg’s grant application,” says Dinant. “But on January 1, I woke up to multiple missed calls from the fire department and the police. A terrible start to the new year.’

Cross vaults

The owner of the chapel, who could not be reached for comment on Monday, is “in principle” well insured against fire damage, according to architect Dinant. The possibility that the municipality, which has to ensure the conservation of the monument, has to pay the costs, he considers small.

In order to be able to examine the damage, the chief sexton Velthausz leads across a wooden bridge in the ridge of the Sint-Lambertus church to a skylight. He points to the bulges under the walkway along the road. They are the tops of the vaults in the church ceiling. Cuypers experimented in Veghel with a technique that had been lost in the Middle Ages. And with success, witness the “ribbed vaults” in the church of Lambertus.

From the window in the roof of the stern of the Sint-Lambertus you can see what remains of the chapel. No more than four walls, with five so-called pinnacles on the facade, pointed decorations of Gothic architecture. It’s surprising that these hallmarks are still standing. Due to overdue maintenance, the rickety turrets were already attached to the roof with steel cables years ago, a roof of which there is now nothing left. Three of the five steel cables hang lazily in the black hole.

Van Asperen is pleased that at least the masonry has been preserved. He points to rows of yellow stones that form a band around the chapel every few layers. “I have never seen such a ‘layer of bacon’ from Cuypers, apart from the church of San Vito in Hilversum,” says Van Asperen. For him it is a confirmation that the work should be mainly attributed to his son Jos, with whom Van Asperen contradicts the Cultural Heritage Agency of the Netherlands.

Beautiful brickwork

Be that as it may, it is the umpteenth time that a Cuypers project has been hit by fire. In 2013, the Sint-Clemenskerk in Ameland was on fire. An attempt has been made to reconstruct Cuypers’ design as original as possible using old photographs. Five years later, the Sint-Urbanuskerk in the municipality of Amstelveen burned down completely, except for the turret. There, too, work is being done to restore the distinctive Cuypers facades and vaults.

This turn of the year, the Fire Department’s Control Room received 134 reports of a fire in a home, 65 times in another building type. By way of comparison: Last November there were an average of 21 house fires per day. Even monuments sometimes fall prey to flames. Three years ago, on New Year’s Eve, a monumental windmill from 1849 in the West Frisian village of Bovenkarspel was destroyed by fire. The fireworks were almost certainly to blame, the miller said at the time NO. The mill has now been restored and the blades are turning again.

Joop Schevers (78) stands in front of the fences around the chapel of Veghel, who came to view the devastation on his electric bicycle from his hometown of Schijndel. “I’ve been building bricks for 50 years,” he says. ‘So beautiful masonry is no longer made. Too expensive. What remains of the chapel can therefore never be demolished”.

Schevers can draw hope from the judgment of Cuypers expert Van Asperen, himself a “retired architect”. After his tour around the chapel, he resolutely says, ‘This can be saved.’