Table of Contents

- 1 Patterns of abuse

- 2 Vulnerability and policy choices

- 3 Who bears the risk?

- 4 Welfare checks

- 5 Backing our own laws

- 6 Given your expertise, what strategies would you recommend for raising awareness about the rights of domestic workers employed by foreign diplomats among relevant stakeholders, including government officials, NGOs, and the public?

In a cost-of-living crisis, many workers in Australia are doing it tough, but spare a thought for people being paid 65 cents an hour.

If you wanted to catch a bus, you would need to work for about four hours to cover the cost of a one-way, off-peak fare.

If you wanted to make a phone call, you would need to work for about a week to cover the cost of the cheapest monthly phone plan on the market. That is assuming you have a handset.

But surely in modern-day Australia, no one would tolerate working for less than one dollar an hour?

And yet, recent federal court cases have heard that some domestic workers employed by foreign diplomats in Australia have been paid as little as 65 cents an hour.

Patterns of abuse

It is a little-known quirk of the diplomatic system in Australia, diplomats are able to bring in a domestic worker to work for them.

I first became aware of the risks of abuse and exploitation inherent in this situation back in 2009, researching labour trafficking for the Australian Institute of Criminology. My report gave examples of domestic workers who had allegedly not been paid but also threatened with visa cancellation, had their movements restricted and in some cases been subjected to violence.

Efforts have been made by successive governments to improve the protection available to these workers.

Today, visa conditions for domestic workers include a requirement that they have an employment contract that meets Australia’s workplace relations and have the support of the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade.

Dfat protocols require diplomats to sign various forms acknowledging that labour laws apply to domestic workers.

But here’s the catch.

Once diplomats have signed these forms, there appears to be no effective system to ensure that these conditions are met. To the best of my knowledge, welfare checks on workers are not done. And once a diplomat has left the country, these workers have little to no chance of ever seeing payment, even if they have a court order in their favour.

Vulnerability and policy choices

One reason these cases persist is the power imbalance built into these relationships.

Ambassadors, high commissioners and their deputies are by definition people who are held in high regard by their governments, with special privileges and status here in Australia.

The domestic workers they employ may have limited education and they are disconnected from their support networks. They depend on the diplomats who employ them for their visas, their employment and usually the roof over their heads.

But while vulnerability is a factor, there are policy choices we can be making to reduce the risk of exploitation.

Who bears the risk?

At present, the forms we require diplomats to sign note that one of the consequences of diplomats being found to underpay their domestic staff can include the cancellation of the domestic workers visa.

Surely the reverse would make more sense?

Rather than putting the worker’s visa at risk when they are underpaid by diplomats, we could make the visas issued to diplomats conditional on their meeting Australian employment law for the duration of their stay.

Just as the Department of Immigration raises various debts against other visa holders, any underpayment could be attached as a debt owed by the diplomat to the commonwealth.

Welfare checks

There is no system in place to check on the welfare of domestic workers in diplomatic homes. Given this is a relatively small cohort and the government knows where they work and live, we could immediately strengthen support for domestic workers by connecting each of them to trained outreach workers.

Backing our own laws

In two recent federal court cases, domestic workers have endured multiyear court cases in the hope they would get paid for years of work they did in Australia. Our courts have recognised their claims under Australian laws. But we have not created the mechanisms that would allow us to enforce our own laws.

In the short term, there is a case to be made for the Australian government to make one-off payments to these workers. They have exhausted the limits of our current legal system and surely have endured enough.

But looking further ahead, we need to build the mechanisms to enforce our laws, even when diplomats are involved. This could take the form of a standing fund to draw from in the event that domestic workers remain unpaid by diplomats. The cost should be funded through contributions from every embassy and high commission in Australia wanting to employ domestic workers while here.

There is no justification for allowing serious labour abuses like this to persist over decades.

There are policy choices we can and should be making to change the conditions that enable this exploitation to persist.

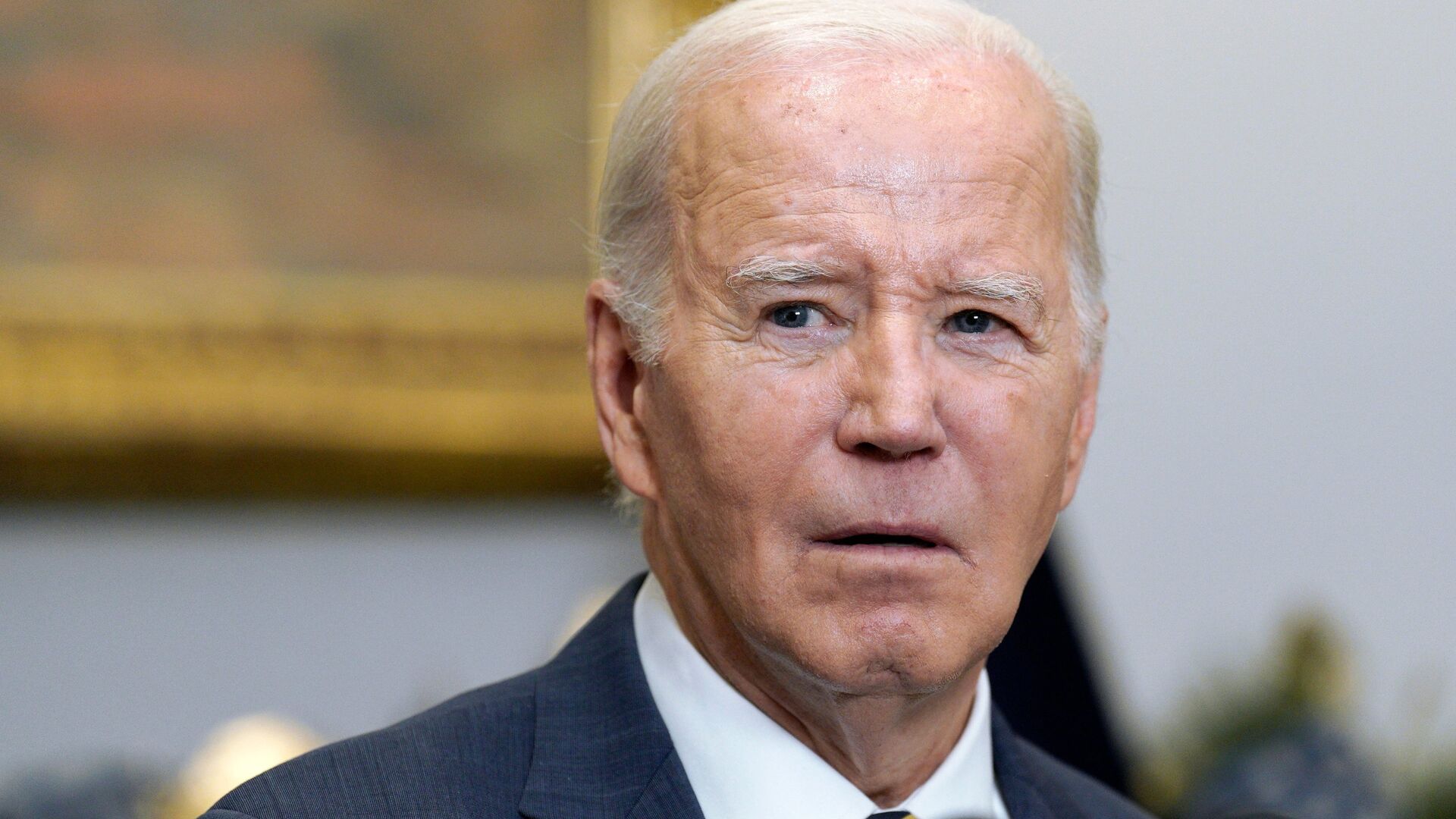

Fiona David is the founder and CEO of consultancy Fair Futures, advising business and political leaders, peak industry bodies, philanthropists and NGOs on the practice of respecting human rights. She is the architect of the Global Slavery Index

Given your expertise, what strategies would you recommend for raising awareness about the rights of domestic workers employed by foreign diplomats among relevant stakeholders, including government officials, NGOs, and the public?

Guest 1: Fiona David, Founder and CEO of Fair Futures

Initial Question: Professionally introduce yourself and your expertise in the field of human rights and labour relations.

As the founder and CEO of consultancy firm Fair Futures, you have extensive experience advising business and political leaders, peak industry bodies, philanthropists, and NGOs on the practice of respecting human rights. In particular, you are the architect of the Global Slavery Index. How did you first become aware of the issue of labour exploitation and abuse within the diplomatic system in Australia? Can you share any specific cases or incidents that sparked your interest in this area?

Guest 2: (To be determined)

Questions related to the article:

1. The article highlights the plight of domestic workers employed by foreign diplomats in Australia, who are allegedly paid as little as 65 cents per hour. What are some of the key challenges these workers face in terms of seeking justice and compensation?

2. Could you discuss the policy implications of allowing diplomats to bring domestic workers into Australia without a robust system of oversight and enforcement? How can we better protect vulnerable workers from exploitation while also respecting diplomatic immunity?

3. What role do you think government agencies like Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT) and Department of Immigration can play in ensuring that diplomatic staff comply with Australian labour laws?

4. The article mentions that domestic workers have to depend on their employers for their visas and often lack support networks here. How can we create a more supportive environment for these workers, both during and after their employment?

5. In your opinion, what are some effective measures that could be taken to ensure compliance with Australian labour laws among foreign diplomats and their domestic staff? Should the onus be on diplomats to prove they are meeting local wage standards or should the burden of proof be on the workers to prove they are being underpaid?

6. Are there any potential unintended consequences of imposing stricter measures on diplomats regarding worker wages, such as strained diplomatic relations with their home countries? How can we balance the protection of workers’ rights with maintaining diplomatic ties?

7. The current legal system seems inadequate in