After the financial crisis of 2007-09, global property prices fell by 6% in real terms. But soon they recovered again and surpassed their pre-crisis peak. When covid-19 hit, economists thought a real estate crash was on the way. And then, from 2021 onwards, as central banks raised interest rates to tackle inflation, fears of a house price scare grew.

In fact, real prices fell by just 5.6% – and are now rising rapidly again. Housing seems to have a remarkable ability to keep appreciating in any case. It will likely defy gravity even more brazenly in the coming years, according to a report in the Economist.

Real Estate: The History of Housing Since the 19th Century

The housing story involves a once remarkable asset class becoming the largest in the world. Until about 1950, property prices in the wealthiest world were stable in real terms. Builders were building homes where people wanted them, preventing prices from rising too much in response to demand.

The development of transport infrastructure in the 19th and early 20th centuries also helped hold down prices, argues a paper by David Miles, a former Bank of England official, and James Sefton of Imperial College London. By allowing people to live further from their place of work, better transport increased the amount of economically exploitable land, reducing competition for space in urban centres.

The events that followed the second world war reversed all these processes, creating the real estate supercycle we are experiencing today. Governments began to subsidize mortgages. People in the 20s and 30s had many children, increasing the need for housing. Urbanization increased the demand for housing in places that were already crowded.

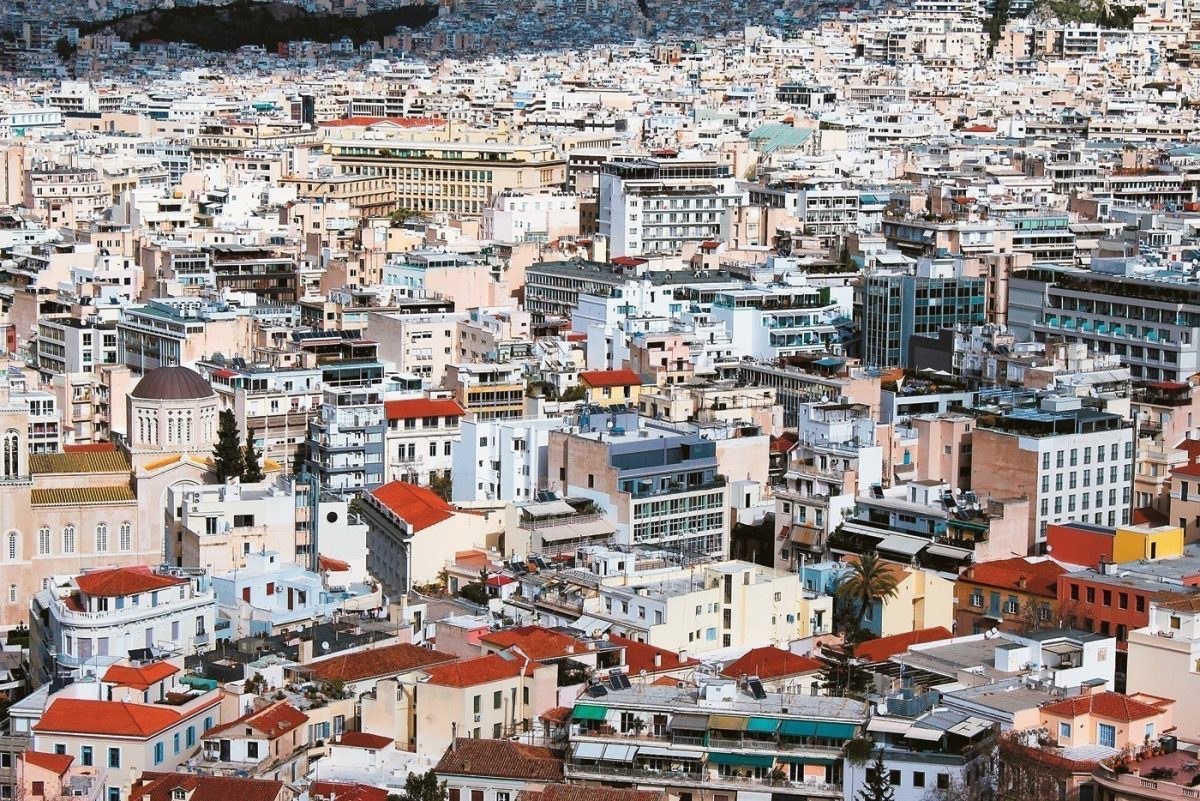

The second half of the 20th century brought a host of land use regulations and anti-development philosophies. Building infrastructure became more difficult, making cities less expandable. Metropolises that once built real estate comfortably, from London to New York, put the brakes on. Across the rich world, housing construction, expressed as a percentage of population, peaked in the 1960s and then steadily declined to about half of today’s level. House prices began to move inexorably upwards.

What happened to real estate in recent years

The past few years have been less disruptive to property markets than even optimistic forecasters predicted three years ago. As central bankers raised interest rates, many mortgage holders felt nothing. Before and during the pandemic, many had loaded up on fixed-rate mortgages, shielding them from higher interest rates.

In America, where many people fix their mortgage rate for 30 years, household mortgage interest payments as a percentage of income remain flat. New buyers face higher mortgage costs. But the rapid rise in incomes is helping to offset this effect. Wages across the G10 group of countries are 20% higher than they were in 2019.

Not everyone is unscathed. In Germany, New Zealand and Sweden, real property prices have fallen more than 20% since the peaks of the pandemic. Elsewhere, however, house prices have fallen only slightly and a boom of sorts is underway. US home prices are hitting new highs almost every month, having risen 5% in nominal terms over the past year. In Portugal, prices are skyrocketing. From 2011 to 2019 house prices in Rome fell by more than 30% in nominal terms as Italy grappled with a public debt crisis. Now they are increasing again.

The prices

In the short term property prices will continue to rise. Falling interest rates help. In America the rate for a 30-year fixed mortgage has fallen by almost 1.5 percentage points from its recent peak. In Europe a wave of fixed-rate borrowers will soon be able to refinance at lower rates as central banks cut interest rates. But there are deeper forces at work. Three factors will ensure that, for decades to come, the housing supercycle will last.

The first concerns demography. It is estimated that the foreign-born population of the rich world is growing at an annual rate of 4%, the fastest increase on record. Immigrants need a place to live, which, according to research, tends to drive up both rents and home prices. A recent paper by Rosa Sanchis-Guarner of the University of Barcelona on Spain finds that a one percentage point increase in the immigration rate increases average house prices by 3.3%.

How does immigration affect

In response to the unprecedented arrivals, politicians from Canada to Germany are restricting immigration. But even with the strictest policies, rich countries will likely continue to take in more immigrants than in the past. Their need to serve an aging population is likely to trump their desire to limit immigration at the border. Goldman Sachs estimates that if Kamala Harris wins the US presidential election, net immigration will fall slightly, to 1.5 million a year from well over 2 million in 2024. If Donald Trump wins with a divided government, expect it to drop to only 1.25 million.

The second factor concerns cities. When covid-19 hit in 2020, many believed that urban areas would lose their luster. The rise of telecommuting meant that, in theory, people could live anywhere and work from home, allowing them to buy more spacious homes for less money.

Telecommuting

It hasn’t worked that way. People are working from home much more than they used to, but big cities retain their appeal. In America, 37% of businesses are located in large urban areas, the same percentage as in 2019. We estimate that the share of total employment in the rich world that takes place in capital cities has increased in recent years.

In Japan, South Korea and Turkey, more jobs are created in the capital cities than elsewhere. It’s also where they have more fun: the share of Britain’s bars and pubs located in London has risen slightly since before the pandemic. All of this increases competition for living space in compact urban centres, where housing supply is already limited.

The triumph of the city magnifies the effects of the third factor: infrastructure. In many cities, commuting has become more excruciating, limiting how far people can live from their jobs. In Britain, average commuting speed has fallen by 5% in the last decade.

In many American cities, traffic congestion is near historic highs. Many governments find it almost impossible to build new transport networks to ease the burden of commuting. California’s high-speed rail, intended to connect Los Angeles to San Francisco and much of the potential living space in between, will probably never be built.

The “YIMBY” movement

Some economists are hoping that there is a turn to “YIMBY”. The “YIMBY” movement (short for “yes in my backyard”) is a pro-housing movement focused on promoting new housing, opposing density limits (such as the single-family home), and supporting public transportation. It stands in contrast to the “NIMBY” (“not in my backyard”) trend, which generally opposes most forms of urban development in order to maintain the status quo.

People who say yes to having new properties “in my backyard” have won the argument and seem to have converted some politicians. A few places are following the “YIMBY” playbook, changing land use rules to encourage building. In early 2022 New Zealand house building permits reached an all-time high, helping to decelerate property prices.

Beyond New Zealand, however, YIMBY’s influence remains marginal. A paper by Knut Are Aastveit, Bruno Albuquerque and André Anundsen, three economists, finds that the US “elasticity of housing supply” – the degree to which construction meets higher demand – has declined since the 2000s. We find no evidence of a generalized rise in construction after the pandemic.

The supply problem remains more acute in cities. In San Jose, America’s most expensive city, just 7,000 properties were approved for construction last year, far less than a decade ago. But even in Houston and Miami, which pride themselves on avoiding the mistakes other big cities made, building is slow.

In the coming years, real estate markets could face all kinds of shocks, from fluctuations in economic growth and interest rates to bank failures. But with the long-term effects of demographics, urban economics and infrastructure aligning, let’s consider a prediction made in 2017 by Messrs Miles and Sefton. It finds that “in many countries it is plausible that house prices could now rise persistently faster than incomes”. The world’s largest asset class is likely to get even bigger.

Source: ot.gr

#Housing #Soaring #property #prices #coming #years #reasons

/img-s3.ilcdn.fi/5e84bca2f1875459e4de9a9d66c53129882233764dd92477ae5936c096c016af.png)