Somewhere deep within a Greenland glacier lie the remains of Camp Century, a short-lived experiment in making the Cold War a reality.

In 1959, the United States Army began building a network of tunnels, carved into the ice, which it hoped would become a site of launching of nuclear missiles.

By 1967, the army had abandoned the idea and the base.

But samples of ice and frozen sediment that scientists extracted from the depths of Camp Century continue to provide new insights into the planet’s history.

When Paul Biermana geologist at the University of Vermont, began studying some of these samples, and made a surprising discovery.

Scientists had once believed that the Greenland ice sheet had been largely stable over the past 2.6 million years.

But what Bierman and his colleagues saw under the microscope provided clear evidence that parts of the ice sheet had temporarily melted much more recently.

About 400,000 years ago, the site had been ice-free.

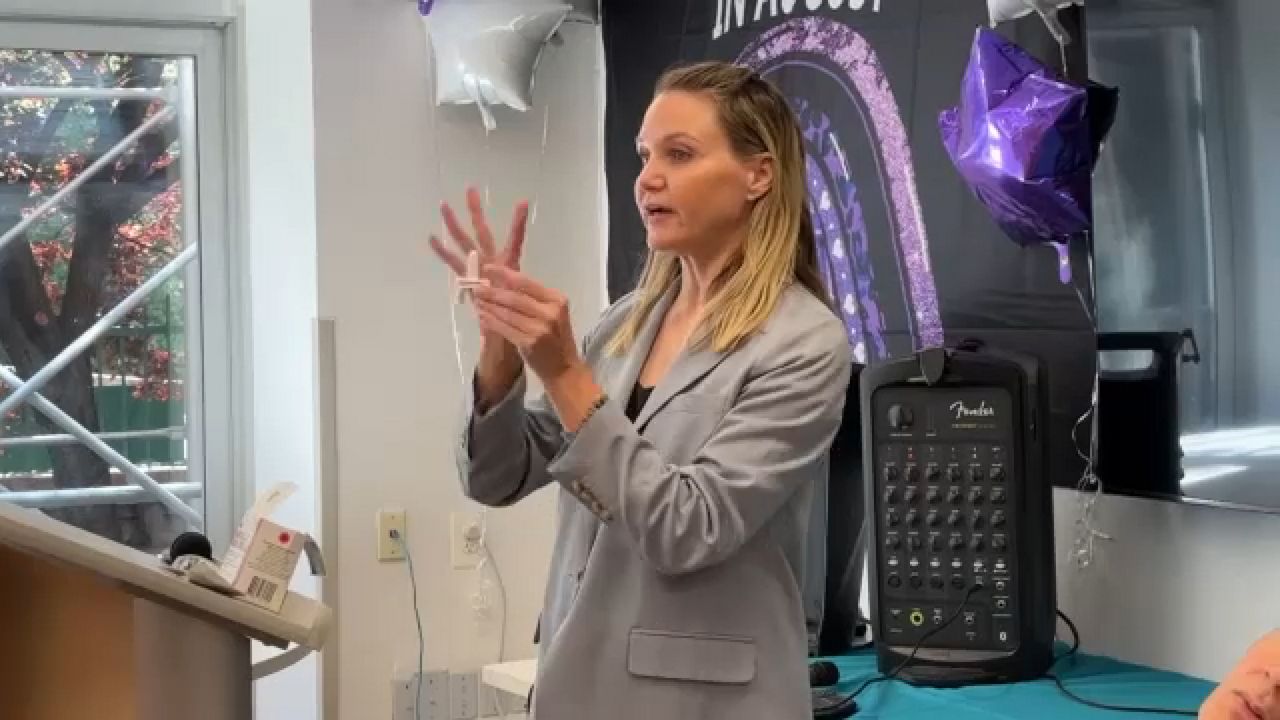

Paul Bierman, a geologist at the University of Vermont, in his lab, with fossils recovered from two miles beneath the Greenland ice sheet projected behind him. In a new book, geologist Paul Bierman recounts the moment he found astonishing evidence that the Greenland ice sheet had melted in the distant past. (Joshua Brown/University of Vermont via The New York Times)

Bierman spoke with The New York Times about this discovery, which he recounts in his new book, “When the Ice Is Gone” (When the ice is gone)

(This conversation has been condensed and edited for clarity.)

Q: We wouldn’t have these samples if it weren’t for Camp Century. What was the military doing in Greenland?

A: That started in World War II. Greenland is upwind of the European theater, so to do weather forecasting, they needed soldiers on the ground in Greenland.

It was also the shortest route to get planes from the US to the Allies.

The U.S. gained a foothold in Greenland and realized it didn’t know much about the science of cold regions.

The men stationed there did not have proper sleds, could not move safely across the ice, and did not understand how ice and snow behaved.

So the US military started investing a lot of money in ice.

They built several camps under the ice and then began drilling into this deep ice core at Camp Century.

When they reached the bottom of the ice sheet, they continued and brought almost 3,6 metros of what we call sub-ice material, that is, frozen land and water. It was a novelty.

Within a couple of years of bringing that core to the surface, and looking only at the clear ice part, they discovered more than 100,000 years of climate history, but they ignored the bottom sediments.

In 2019, we were given samples of that material from the bottom.

And that’s when things got really fun.

Q: In your book, you say that these samples led to the only real eureka moment of your scientific career. Tell me about that.

A: The samples appeared on a very hot July afternoon in a DHL box with many freezer packs.

We smelled an incredible smell of diesel fuel, because in the 1960s they used a mixture of diesel fuel and trichloroethylene (which is a dry cleaning fluid) to keep the hole in the ice open while they were drilling.

We were sifting these samples, which involved trying to classify them by grain size.

So we took out the pebbles, the sand and the silt.

Everyone involved was hot and tired, and I was absentmindedly staring at this container of water with the sandy fraction.

Suddenly, I saw little black specks floating on top, and I was kind of shocked.

I looked at the two people with me and said:

“I think we have fossil plants here.”

I took a pipette and squeezed out these little black specks.

Drew Christ, who was a postdoctoral fellow with me, put them under the microscope.

And there was about 10 seconds of deathly silence before he raised his head with a series of cheerful expletives.

We were looking at the plants growing where the ice cap is today.

It wasn’t long before the three of us stopped chattering that we realized that this was probably the greatest discovery any of us had made in our scientific lives.

From then on, we continued to find fossils:

mushrooms, insect parts, small pieces of wood, leaves, moss, a poppy seed. It’s impressive.

Q: What was so impressive?

A: It turns your stomach to see a poppy seed where there are now miles of ice. It’s the kind of evidence that everyone understands:

Today it is ice and yesterday it was plants.

It didn’t take us long that day to have one of those moments of, “Wow, this is cool, and wow, this is scary.”

Because it all happened before we started changing the climate. So now we know that Greenland can melt on its own, and what are we doing? We’re giving it a big kick in the butt to melt even faster.

So now we know that Greenland can melt on its own, and what are we doing?

We’re giving it a big kick in the butt to melt even faster.

But humans were clever enough to figure out, in the 1950s, how the ice sheet worked, how to live on it, and how to drill an ice core.

I don’t think saving the Greenland ice sheet is impossible.

I think it’s going to take that same kind of determination.

c.2024 The New York Times Company