When commemorating the passage to immortality of General Don José de San Martín, one of the most important referents of the South American independence process at the beginning of the 19th century, it is interesting to discuss the role that Afro-descendants had in their armies.

There was not a single Argentine battalion that did not have the presence of Afro-descendant soldiers, key in the battles of San Martin. Their participation within the so-called “Pardos y Morenos” regiments is usually recognized. But they were not only limited to these regiments. The enslaved were forcibly incorporated into the armies by a decision of their owners. It is also reported that after their participation in the independence armies they would be released, but as an example one can take what happened during the English Invasions where Battalion No. 17 of Pardos y Morenos participated. As a reward for their courage in combat, some seventy slaves out of a total of six hundred and eighty-six slaves that comprised the battalion were awarded with their freedom, by means of a “draw.”

The prevailing racial segregation influenced the creation of battalions and regiments of Pardos and Morenos with which the rest of the soldiers did not want to have contact. Historians report that the “knights” decided not to cooperate with the Army of the Andes “because they were not willing to ride with blacks.” San Martín had arranged for several of the enslaved to fight on the best horses.

In the story of white and European Argentina, the independence wars are used to justify the non-presence of the Afro-descendant population in our country. This is how they tell how the infantry corps, where Afro-descendants mainly worked, were the first line in the confrontations and functioned as “cannon fodder”. On the one hand, the figure of the heroes who led these wars is exalted, but there is no recognition of the participation of those Afro-descendant soldiers. And they are mentioned as soldiers because few Afro-descendants were promoted through the military ranks. San Martín claimed to be able to appoint them to the positions of corporals and sergeants, a heresy for the time.

In the proclamation of San Martín of 1820 one can read: “The rich and the landowners refuse to fight, they don’t want to send their sons to battle, they tell me that they will send three servants for each son so they don’t have to pay the fines, they say that they don’t care about continuing to be a colony. Their children remain fat and comfortable in their homes, one day it will be known that this country was liberated by the poor, and the children of the poor, our Indians and blacks, will no longer be slaves.”

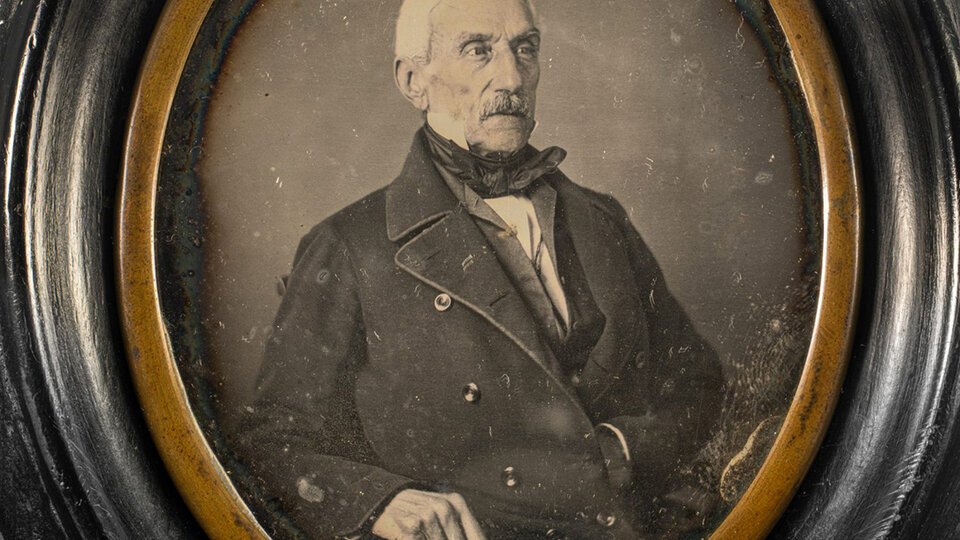

heroic soldier cabral

Associated with the figure of San Martín, the participation of Juan Bautista Cabral and his act of courage in saving San Martín in the battle of San Lorenzo, years before the Andean crossing, is repeated in Argentine historiography. The figure of Cabral reached the national anthems where he is recognized as “Sergeant Cabral” although there are no known records of his appointment as “Sergeant”. In turn, in the representations that are made about Cabral until a few years ago it was usual for him not to be represented as an Afro-descendant, he was whitewashed to reinforce the white-European story. Not much is told about his history, how he came to fight alongside San Martín. On the other hand, his figure was exalted since he died from injuries received during the battle. It is also not explained if there are descendants of him. The false belief that there are no Afro-Argentines in our country is fulfilled because they died in the wars of independence. In the film “Revolution. The crossing of the Andes” is represented as Afro-descendant.

The Crossing of the Andes

The Army of the Andes had approximately 5,000 troops, of which it is estimated that between 40% and 50% were Afro-descendants. In the Cerro de la Gloria monument located in the City of Mendoza, the Afro-descendants who participated in the Army of the Andes were immortalized. Members of Regiment No. 8 of Libertos left for Mendoza from Buenos Aires. At the same time, San Martín expropriates enslaved people from the Municipality of Cuyo.

Another of the Afro-descendants who accompanied San Martín was Juan Isidro Zapata who served as his trusted doctor, he was the only one who attended and knew all the many ills he suffered.

The first military band of the Liberation Army was made up of twelve enslaved blacks, who were sent to Buenos Aires to train as musicians and form the “Banda Talcahuano”. Second Corporal Antonio Ruiz, better remembered as “Falucho” was also part of those who fought alongside San Martín.

When San Martín arrived on the Peruvian coast, in 1820, he was presented with some slaves fleeing from neighboring haciendas and wishing to enlist in the independence army.

In short, vindicating the history of Afro-descendants in San Martin’s campaigns not only enriches our understanding of the past, but also results in an act of historical and racial justice. By remembering and acknowledging his legacy, we not only honor his memory, but also enrich our understanding of history and forge a stronger bond with our nation’s roots.