After 2011, Norwegians did not even want to say Anders Breivik’s name. As if evil existed somewhere outside of us. “But I insist that evil is always done by us humans,” says Norwegian journalist Åsne Seierstad, who presented her book about the country’s mass murderer at the Author’s Reading Month festival this month.

The event, which takes place in Brno, Ostrava, Bratislava and Lviv, Ukraine, will last until July 31. Norway is the guest of honor this year.

Among the main stars was 53-year-old Åsne Seierstad, who became famous for her war reports from Iraq, Afghanistan and Chechnya. She was a correspondent in Russia and China, selling two million copies of a book called The Book Buyer of Baghdad worldwide. In Czech, the Absynt publishing house also published her Two Sisters, about Norwegian women of Somali origin who left to fight on the side of the Islamic State, and the publication Jeden z nás.

This literary report tells about July 22, 2011, the most tragic day in Norway’s modern history, when the far-right extremist Anders Breivik injured 69 members of the Social Democratic Youth on the island of Utøya. Another eight people died in the explosion of a planted explosive.

“If a person lacks parental attention, love and admiration, which was all Breivik’s case, he will later look for them on a bigger stage,” says Åsne Seierstad in an interview for Aktuálně.cz.

You called the book about the mass murderer Breivik One of Us. What did you mean by that?

A lot of things. First, the book came out quite late. It occurred to me that we have already seen all possible labels like The Norwegian Tragedy somewhere. I wanted a name that included him, his victims, but also us, and now I don’t just mean Norway, but Europe. Most readers associate the story with one country, but you can also think about the title in another sense. For example, if you look at Bano, an eighteen-year-old Kurdish girl who was one of the first victims of Breivik’s shooting at Utøy. She bought Norwegian folk costumes because her biggest dream was to become “one of us”. She gave up at seventeen. She was under the impression that because of the color of her skin, she wouldn’t be able to do it anyway. Being one or one of “us” is complicated. At the same time, in the negative sense of the word, I had in mind the now-forgotten young Russian nationalists who called themselves Ours, and finally Breivik himself. The name is layered, but many, including my father, find it controversial. Remember that after 2011 in Norway, people didn’t even want to say Breivik’s name. As if evil existed somewhere outside of us. But I insist that evil is always done by us humans.

Then, as a reader, I have to ask, why read six hundred pages about a man who commits evil and not about his sixty-nine young victims?

I asked myself this exact question at the beginning. Can they meet in one book? He shouldn’t even touch them! Should their stories be separate? Shouldn’t there be a blank page between the victims and the killer? However, one gradually gets to the core, i.e. the terrible scene where Breivik kills his victims. I started writing about the victims – but I ran into an unfortunate limitation of how interesting they were from a literary point of view. Most of them are around eighteen, model students, capable and passionate, the ideal of a teenager. I read their homework on refugee rights or saving the planet, and I wondered what a nut they would make of life characters. They were so perfect. It dawned on me that I’m not writing their obituary, I need to find the weak spots.

For Simon Sæbø, this is the only time his team plays in the Norwegian Football Cup. Simon excels, but his team loses. He says to his father, who coaches the team: I should play more often because I’m better. We’re losing, but we wouldn’t have to if you put me on more. His father tells him that everyone gets the same opportunity. In another country, the coach might send the team’s best player on the field more often, but not in Norway. It was important for me to record this story as a portrait of a boy eager for life.

What do you think is the core of the tragedy?

If we look at Breivik, one core of the problem turns out to be precisely the absence of a core, his own “I”. The first eighteen months of life are crucial for personality stability, say psychologists. The worst is the lack of affection and the uncertainty of acceptance. Without one’s own “I”, a person cannot develop empathy. If he lacks parental attention, love and admiration, which was all Breivik’s case, he will look for them later on a bigger stage.

The writer Åsne Seierstad signs autographs for the visitors of Author’s Reading Month. | Photo: Kateřina Rusňáková

To make up for them?

Yes, and when we ask for the psychological or political causes of that catastrophe, we find both. Something vulnerable can be seen in his later efforts to succeed. He wants to shine, to be a recognized graffiti artist, but he has no talent, he is not the type of person that others would follow. He’s trying to get rich. He eventually moves in with his mother. He plays computer games for three years, gradually moving to the darknet, where he becomes an easy target for political propaganda. It’s like dynamite for a weak personality with a penchant for grandiosity.

Reading about Breivik can be emotionally difficult. What was it like to write about him?

I often pounded the keyboard with great rage. After all, the killer didn’t even know his victims! Other times I felt a heavy sadness for those young people like Bano or Simon. And certainly disgust at how stupidly the attacker was thinking.

I don’t know what disgusts readers the most, but it’s okay to be disgusted by the reading. When Breivik finally wrote me a letter, I also had to sit down.

How did he affect you?

I wrote a comprehensive book about him and it seemed logical to me as a journalist to offer him an interview. His lawyer advised me to send him a letter. I put an envelope with a stamp inside, wrote my address. And then one morning I take my son to kindergarten and he fishes out a letter from the clipboard that I recognize by his handwriting. Subconsciously, I immediately removed it from the child’s reach. After returning from kindergarten, I had to sit down when I read. ‘Dear Mrs. Seierstad, I am honored that a famous author writes to me, an ordinary person. Of course, I would like to collaborate on the book, but I have several conditions. I would like to write some parts of the book myself, you can write the beginning and the end,’ he told me.

I had to react professionally and politely reply that I would not agree to his terms.

Writer Åsne Seierstad (center) at the Author’s Reading Month festival in Brno. | Photo: Kateřina Rusňáková

How did Breivik’s murders change Norway itself?

At first we were shocked that it was not al-Qaeda’s act, but “one of us”. What followed was the shock of how our police had failed; we usually find the system efficient and fast. But the trial and everything that happened afterwards, I think Norway managed, and so we went through the catharsis together and experienced the national mourning. It was our trauma, our collective loss.

In the meantime, several books have been published by members of the Norwegian Labor Party, peers of the murdered teenagers, who are now in their thirties. They expressed the feeling that they felt left out, because Breivik did not attack all of Norway, but the youth organization of this particular political party. They criticized the prime minister at the time, today’s NATO chief Jens Stoltenberg, for keeping this part of the story under wraps. I interviewed him ten years after the incident. Politicians often say they are sorry, but he meant it. He regretted that he had not realized how important it was to the members of the Norwegian Labor Party that Breivik had chosen their youth and their values.

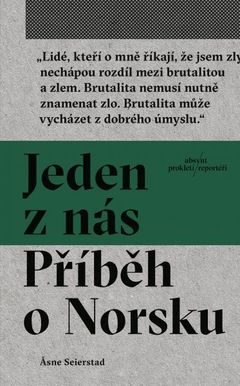

Cover of the book One of Us. A story about Norway. | Photo: Absynt publishing house

And how did the book about Breivik change your life?

I have often read in reviews that reading the details of the Utøya massacre must be too painful for the parents of the murdered children. But that is a misunderstanding. The parents know from the files exactly and in detail what happened to their children on the island that day. They talked to the doctors, saw the fatal wounds, read the autopsy reports. It was my parents who urged me not to miss a single drop of blood in the book.

The stories of them and the victims remain in my life. I was shocked by how the father of the murdered Simon blamed himself for the upbringing he gave his son. Why didn’t he run when Breivik started shooting? Why did he help others in the first place? He was a good swimmer, he could save himself by jumping into the water! You see a father who supported and loved his offspring struggling with such questions – his son helping others instead of thinking of his own salvation first. And against him stands a young man with a gun, who has never received any support from his parents in his life, and destroys others. Simon did what was right, but the thought is excruciatingly painful for his father. No one is raising children to survive a terrorist attack.

Many of the affected parents are still not working. Others, on the other hand, in order to drown out the pain, took on so much work that they collapsed. We all carry trauma differently.

But I will tell you how Simon’s mother entered my life. When I first arrived to see Simon’s parents, they took me to the cabin and she brought out a big box of menthol cigarettes. She said she was so stressed about my arrival that she started smoking. The two of us literally smoked through the interview and drank local vodka. She was lying on the couch, smoking, overeating. Later, he calls me out of the blue: ‘I started smoking because of you. And now you have to help me get fit again.’ So we signed up together for the ski marathon on Svalbard. When I met Jens Stoltenberg and told him about our plan, he wanted to join. All three of us ran the marathon.

Video: Åsne Seierstad at the Author’s Reading Month festival

“The book should be wiser than its author,” says war reporter Åsne Seierstad, author of a book about the murderer Breivik. Photo: David Konečný | Video: Windmill Publishing House