Recessionary indicators give clear warning signals.

However, the Fed remains focused on the fight against, as Chairman Jerome Powell said more than once after last week’s FOMC meeting. During his, in particular, he made two critical remarks.

First, Powell noted that inflation remains too high and still well above the Fed’s 2% target. He also pointed out that the banking crisis will lead to tightening of lending standards, with the effect on the economy and inflation being comparable to “tighter policies”.

As you can see, credit conditions have tightened markedly, which always precedes a recessionary slowdown in economic activity.

Banks with tightened lending standards

Although the market is beginning to quote just one additional Fed rate hike, the lagged effect of the rate hike remains the main risk.

The Fed’s problem is that many economic indicators remain strong, from the recently released statistics on and ending. However, this is largely an illusion due to the initially sharp increase in consumption after large-scale fiscal and monetary stimulus to the economy.

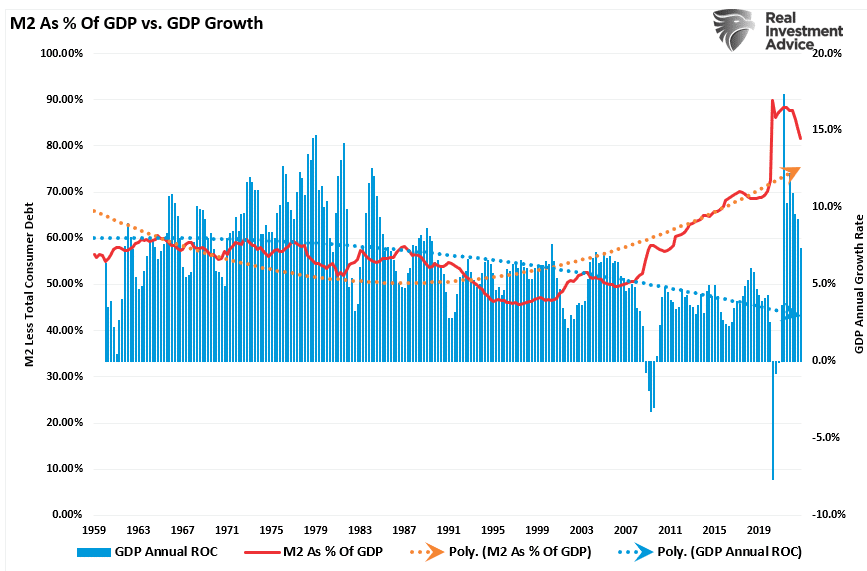

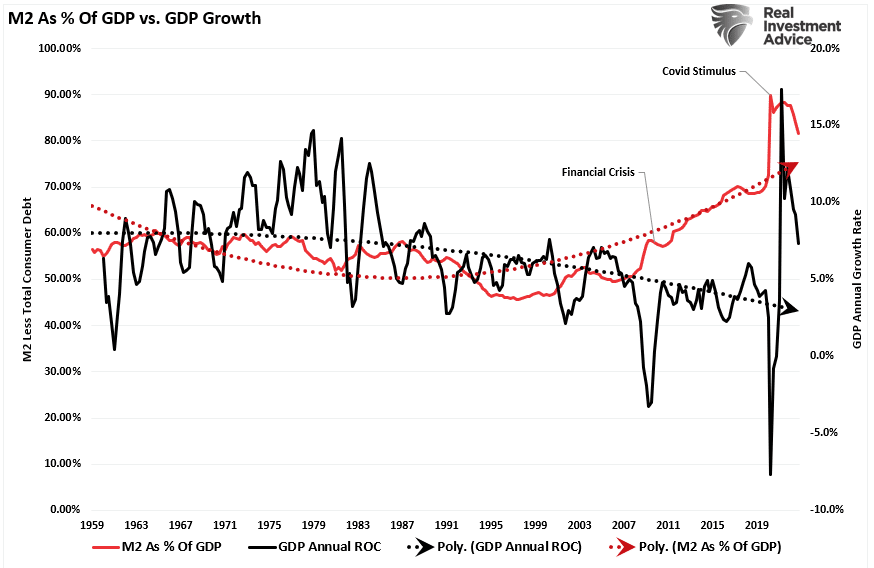

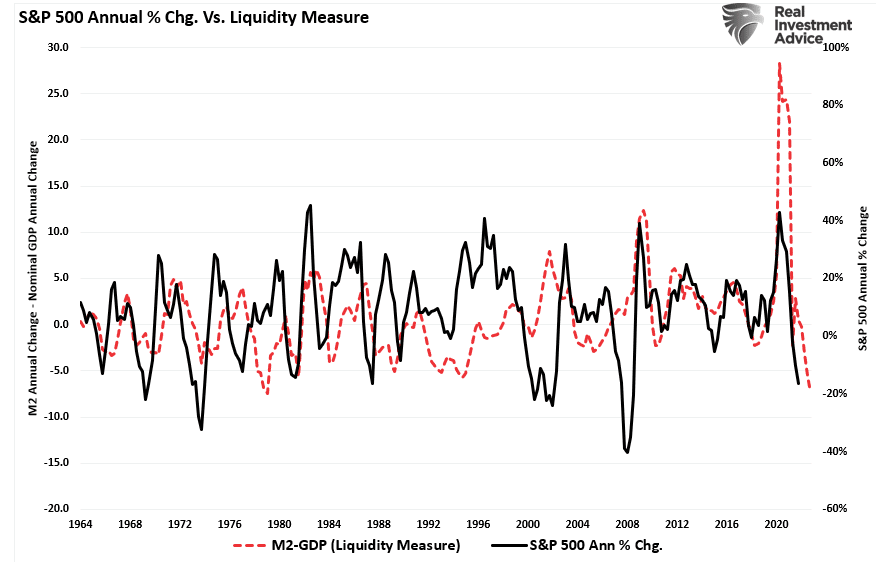

As can be seen, the monetary aggregate (an indicator of the liquidity of the money supply) remains strongly elevated as a percentage of . This “boar in a python” is still being digested by the economic system.

It will take a long period of time for the situation to reverse after a strong deviation from previous growth trends. That’s why recession warnings started early, and the data continues to surprise economists.

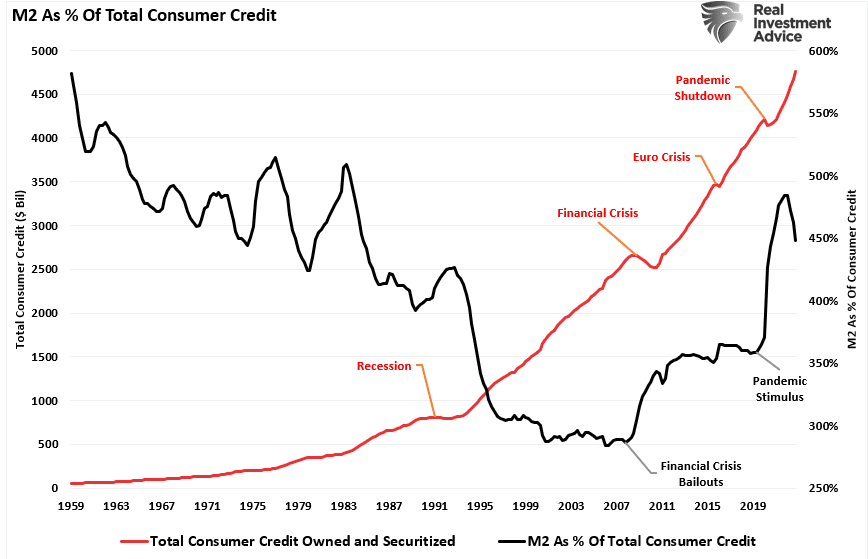

Given that they provide about 70% of economic growth, it is quite natural now to increase debts, with the help of which consumers “make ends meet” after that liquidity impulse has faded.

It can be seen that with the liquidity impulse after crises, the volume of consumer debt decreases for a while. However, as we noted earlier, it becomes impossible to maintain the same standard of living without loans.

Therefore, once the liquidity momentum wears off, the level of consumer debt invariably rises again.

Deflationary monetary and fiscal policy

Unfortunately, the Fed and the government fail to grasp that monetary and fiscal policy becomes “deflationary” when it is financed with debt.

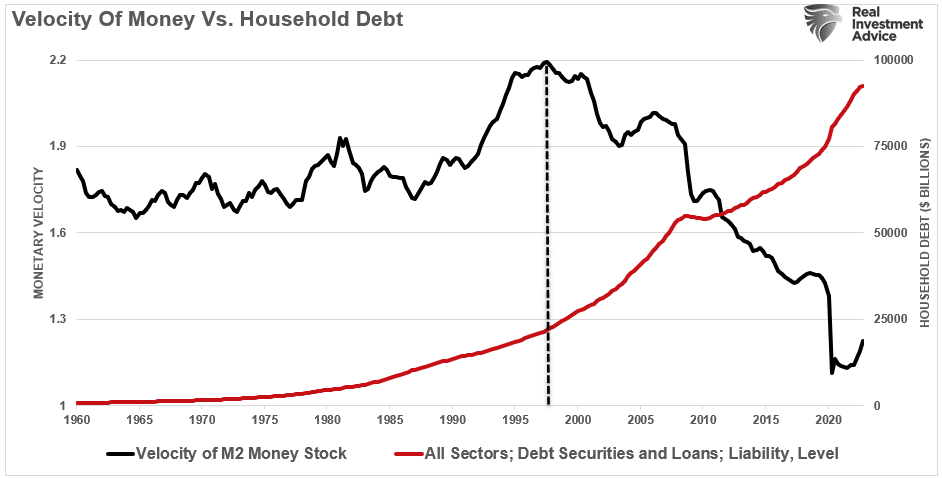

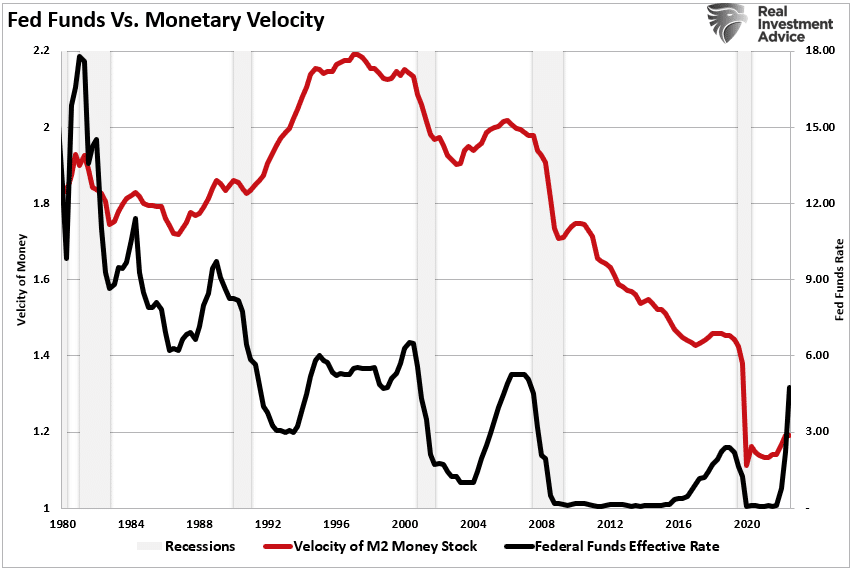

How do we know this? We know this thanks to the concept of “velocity of money”.

What it is?

“Velocity of money is used to measure the frequency with which money in circulation is used to purchase goods and services. The velocity of money circulation helps to assess the health and viability of the economy. A high velocity of money is usually associated with a healthy, growing economy. Slow money velocity is usually associated with recessions and downturns.” – Investopedia

With each monetary intervention, the velocity of money slows down along with the breadth and strength of economic activity. While printing money should theoretically lead to increased economic activity and inflation, this does not actually happen.

Since 2000, the “money supply as a share of GDP” has increased dramatically. The strong acceleration of economic activity is now due to the “opening up” of the economy after artificial lockdowns. This means growth is only returning to a long-term downtrend.

The accompanying trend lines show that the increase in the money supply has not led to more sustainable economic growth. Everything is the opposite.

Moreover, the strength of the economy is undermined not only by the increase in M2 and debt. It is also about the constant containment of interest rates in an attempt to stimulate economic activity.

In 2000, the Fed “crossed the Rubicon”, after which it could no longer stimulate economic activity by lowering interest rates. Therefore, the continued increase in the debt burden made a negative contribution.

It is also worth noting that the velocity of money improves when the Fed raises interest rates. Interestingly, like recessionary indicators, which will be discussed below, the velocity of money usually improves shortly before the Fed “something breaks”.

Recessionary indicators sound the alarm

Many “recessionary indicators” are now sounding the alarm, from and to various indexes of industrial and manufacturing production. In this article, we will focus on two indicators related to economic growth and recessions.

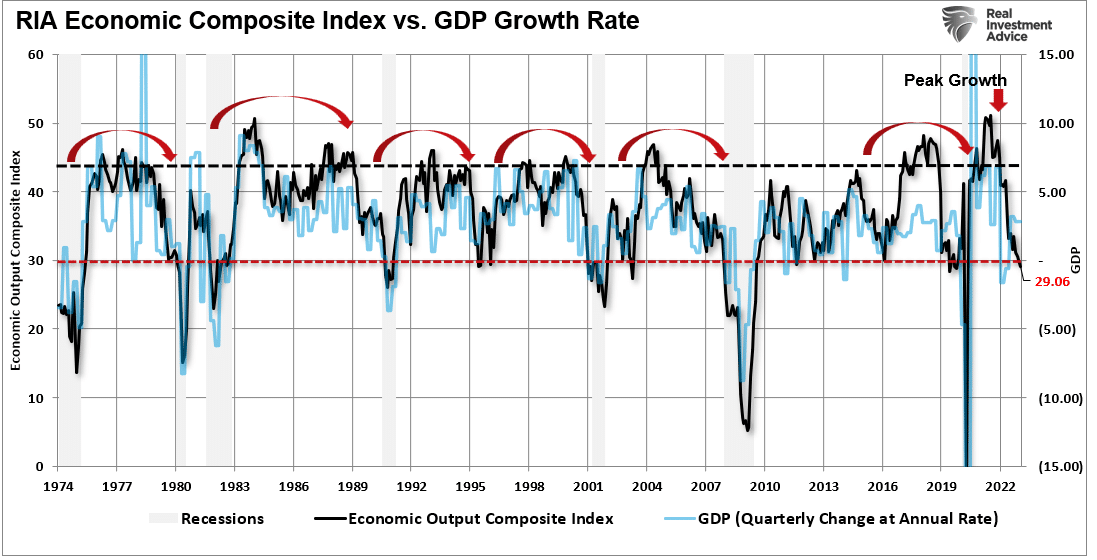

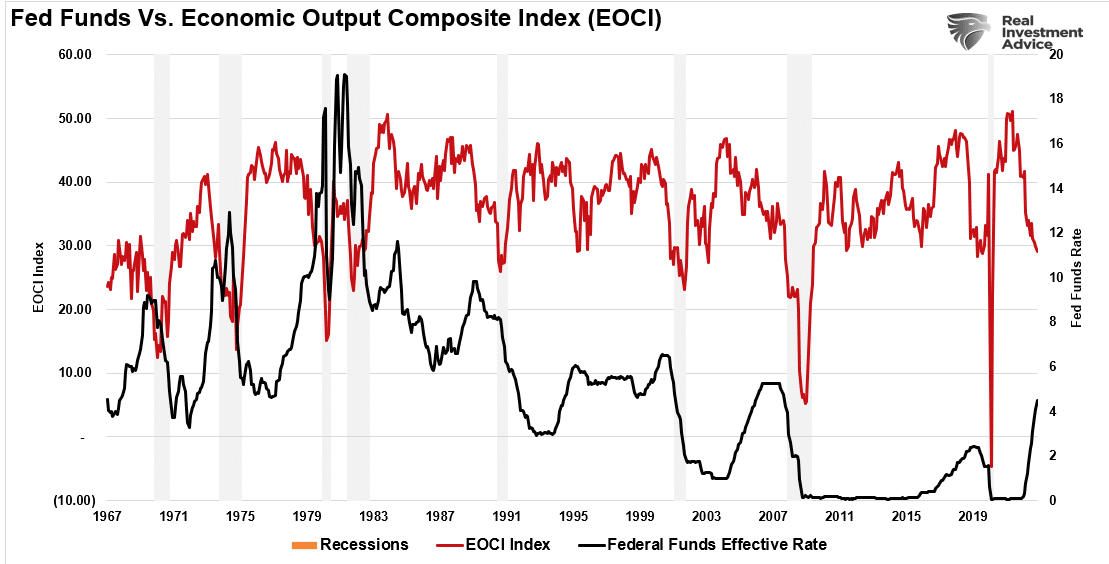

The first of these is our composite economic index, which includes over 100 metrics, both leading and lagging. In the past, a decline in this indicator below 30 was accompanied by a significant economic slowdown or recession.

If the inversion of the yield curve indicates a slowdown in economic activity, then the composite economic index confirms this.

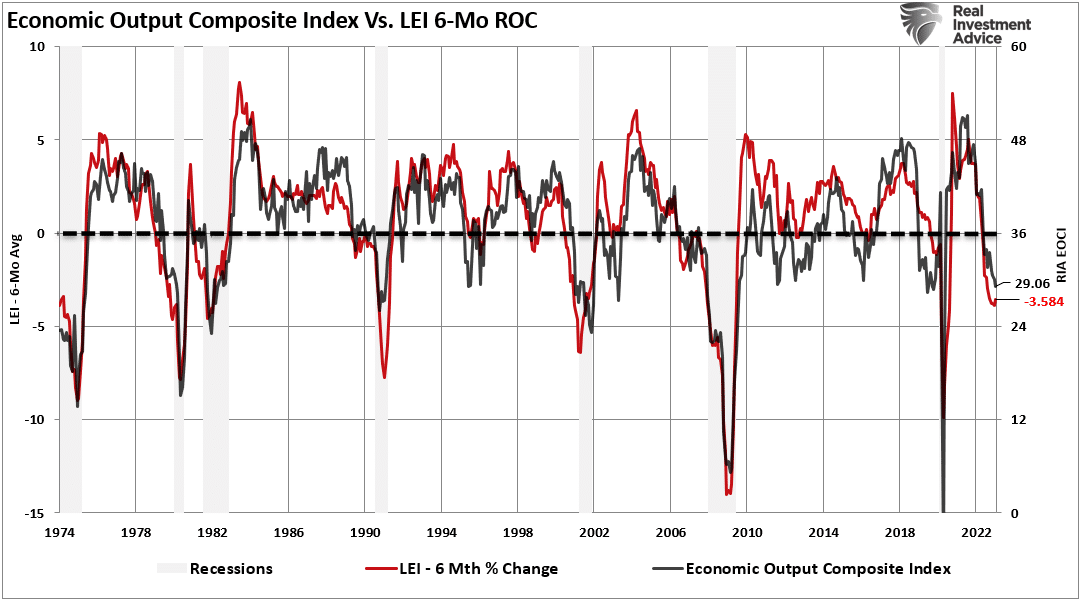

It is echoed by the 6-month rate of change of the Leading Economic Index (LEI), which has proven itself as a recession barometer.

Composite economic index and 6-month rate of change of the leading economic index

Of course, the question today is whether these recessionary indicators are wrong for the first time since 1974. As we pointed out above, the strong increase in the money supply as a share of GDP persists, creating the illusion of a stronger economy than it probably is.

When the lagging effect of monetary tightening comes into full play later this year, the reversal of strong economic performance is likely to surprise most economists.

For investors, the price implications of such a reversal would not be bullish. As can be seen, the contraction in liquidity, expressed by subtracting GDP from M2, correlates with changes in asset prices.

With this reversal process far from over, we should probably expect lower asset prices.

Such a reversal in asset prices will, of course, happen because the Fed “broke something” by tightening monetary policy too much.

The Fed is “breaking something”

As the Fed continues to raise rates to fight the inflationary bogeyman, the bigger threat remains deflation due to the economic and credit crisis caused by excessive tightening of monetary policy.

If you look at past experience, it becomes clear that the Fed is falling behind again. She wants the economy to slow down, not collapse, but the real risk is that “something will break.”

With each rate hike, the central bank gets closer to this undesirable event. When the lagging effect of monetary policy combines with the accelerating deterioration in economic conditions, the Fed’s inflationary problem will turn into a more damaging deflationary recession.

This risk is clearly visible if we superimpose periods of monetary tightening on our composite economic indicator when it indicated recessions.

As long as the Fed is raising rates on inflation fears, the real threat, if things go wrong, will be deflation.

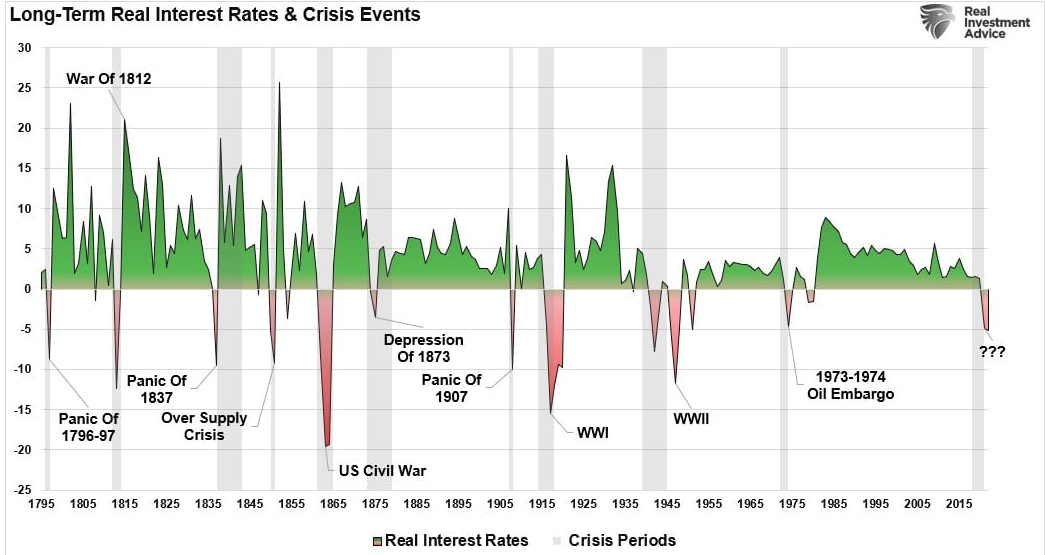

“This is because periods of high inflation also correspond to higher interest rates. In highly indebted economies, like the US today, this leads to a faster destruction of demand, with prices and debt servicing rising, eating into a large share of disposable income. The chart below shows “real interest rates,” that is, inflation-adjusted rates, since 1975.”

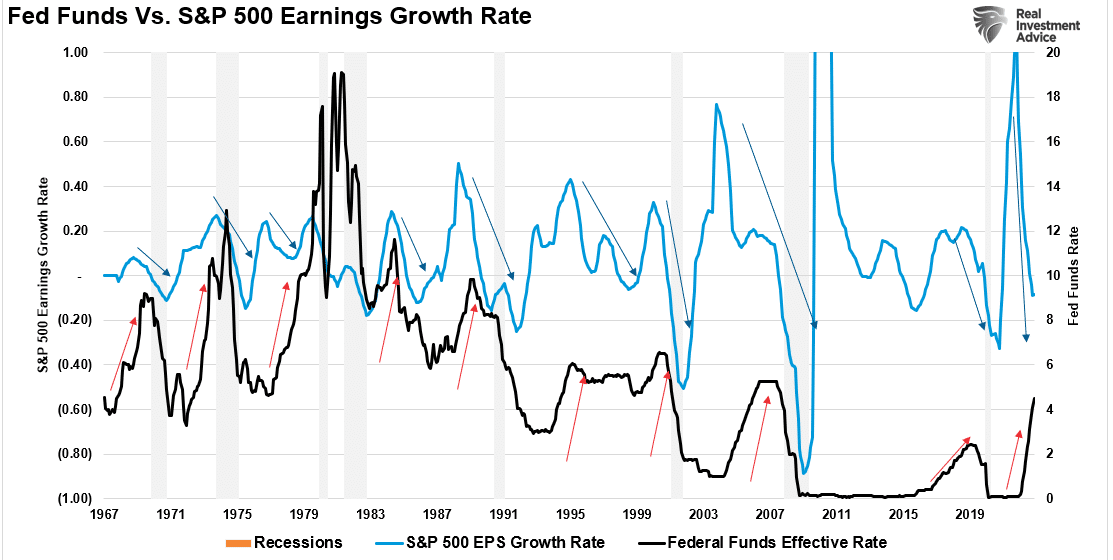

Not surprisingly, each period of high inflation is followed by a period of very low or negative inflation (deflation). For investors, recessionary indicators confirm that the company’s profits will shrink as tighter monetary policy slows economic growth.

Monetary tightening has never had a positive impact on profits in the past and is unlikely to do so this time. This is especially true when the Fed does something “breaks”.

Although this time everything may turn out differently, as an investor I would not bet my pension right now.