Kathmandu –

Nepal has made a remarkable achievement, doubling its tiger population in the last 10 years. This means, bringing back the species from the brink of extinction. But for local people the return of the tiger means something else – increased attacks by the beast.

“There are two things you feel when you are confronted by a tiger,” said Captain Ayush Jung Bahadur Rana, a member of the special unit tasked with protecting the big cat.

“Oh my God, how majestic this creature is. And the other feeling is, oh my God, am I going to die?”

ADVERTISEMENT

SCROLL TO RESUME CONTENT

–

He now sees Nepali tigers frequently, since joining armed forces patrolling the thick open fields of bush in Bardiya, the largest and unspoiled national park in Nepal’s Terai region.

“To be given the task of protecting tigers is an honor. It feels very special to be a part of something so big,” said Captain Ayush, as he looked around the dense forest around him.

Military forces are tasked with protecting tigers from poachers. (KEVIN KIM/BBC)

Approach zero-poaching or zero-poaching that Nepal implements has worked very well to protect tigers.

Nepal’s military has a number of special units tasked with patrolling and assisting guards in national parks.

In the buffer zones surrounding the park, anti-poaching units made up of communities monitor natural corridors through which the tigers can safely roam.

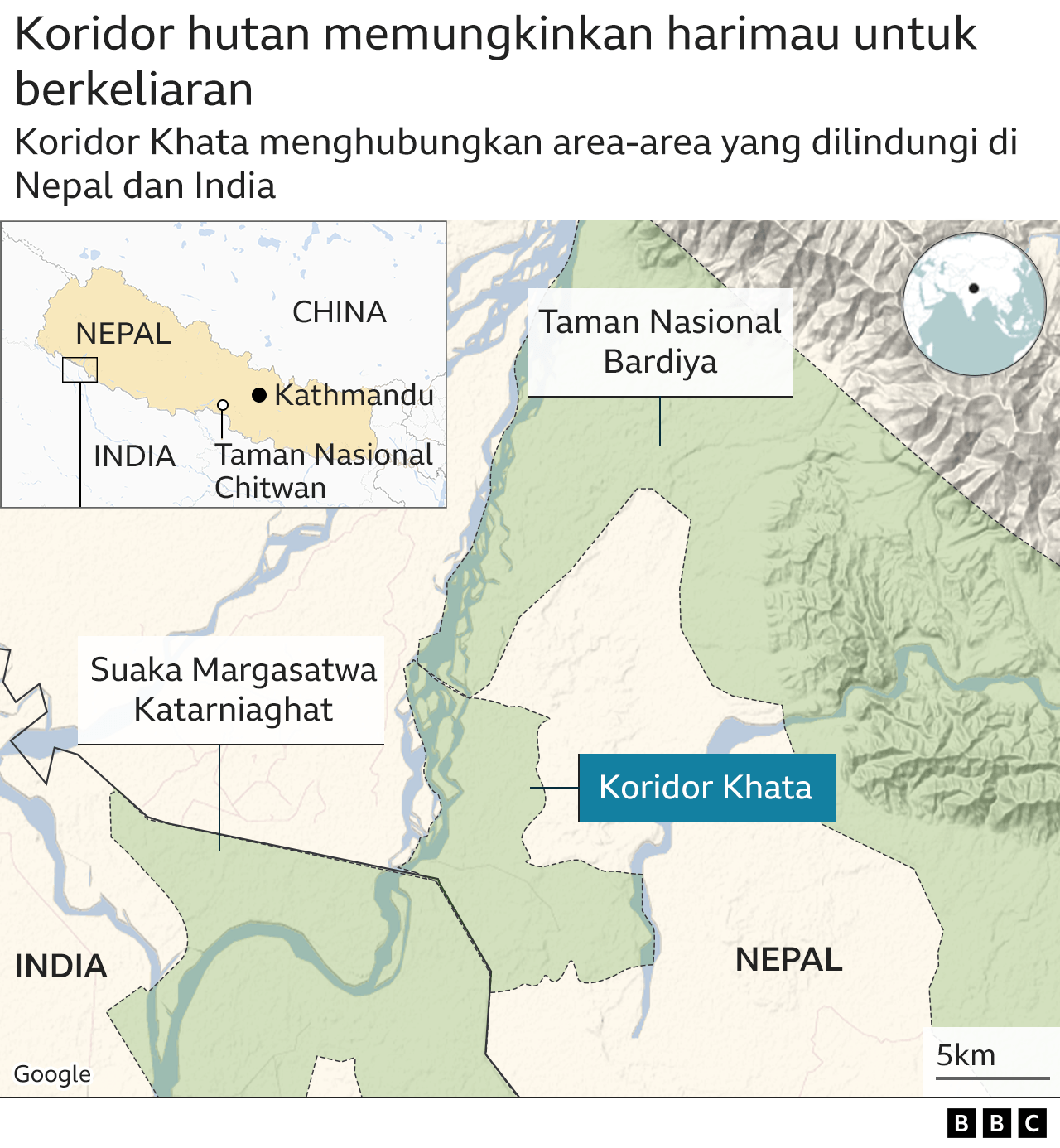

One of those areas, the Khata corridor, connects Bardiya National Park with Katarniaghat Wildlife Sanctuary, crossing the border with India.

BBC

But the return of the tiger population has made life scary for villagers living on the outskirts of the national park.

“People live in terror,” said Manoj Gutam, an environmental business operator and conservationist.

“They share a very small area, between tigers, their prey and humans. There is a price for local people to pay, while the world celebrates Nepal’s success in doubling its tiger population.”

In the last 12 months, 16 people have been killed by tigers in Nepal. In the previous five years, as many as 10 people were killed.

Most tiger attacks occur when villagers go to national park areas or to buffer zones to herd livestock, or pick fruit, mushrooms, and chop wood.

In some cases, tigers emerge from within national parks and nature corridors, wandering into surrounding villages.

There is a fence separating this wildlife from human settlements, but on some occasions, these animals are able to break through.

Bhadai Tharu, a conservationist, lost an eye in a tiger attack. (KEVIN KIM/BBC)

Bhadai Tharu not only has injuries from fighting the tigers he loves and helps preserve.

In 2004, he was attacked by a tiger while cutting grass in a community forest near his village. He lost an eye.

“The tiger pounced on me in the face and then roared loudly,” he recalled, as they replayed the scene.

“I was thrown straight back. The tiger jumped at me again, like a bouncing ball. I punched him as hard as I could and screamed for help.”

When he took off his aviator glasses, something he rarely did, he found a very deep cut and one of his eyes was gone.

“I am very angry and sad. What did I do wrong as a conservationist?” he remembers.

“But tigers are endangered animals, we have an obligation to protect them.”

History shows, the situation is very bleak for the tiger population.

A century ago, there were about 100,000 wild tigers scattered throughout Asia. By the early 2000s, that figure had fallen by 95%, largely due to poaching, poaching and habitat loss.

It is now estimated that there are only between 3,726 and 5,579 tigers in the wild, according to the International Union for Conservation of Nature.

Spanning 968 square kilometers, Bardiya was designated a national park in 1988 to protect endangered animals.

This area was once a hunting ground for the kings.

In 2010, the 13 tiger populations pledged to double the number of wild tigers living on their territory by 2022 – the Year of the Tiger in the Chinese calendar – in a bid to bring them back from the threat of extinction.

Only Nepal has so far hit the target.

The tiger population in Nepal has grown from 121 in 2009 to 355 in 2022. These big cats are commonly found in five national parks dotted across the country.

The number of other animal species including rhinos, elephants and leopards has also increased.

The forests where tigers used to live are now being monitored so they can live safely. (DEEPAK RAJABANSHI)

To maintain the health of the wild tiger population, park authorities have created more grazing areas.

They also increase the number of water inlets to create an ideal habitat for deer, the tiger’s main game.

Bardiya Bhisnu Shrestra, the head of National Park Security, denies that human intervention has gone too far, despite helping tigers to live and breed.

“Now we have sufficient space and a large game population within the park, so we are dealing with these tigers in a sustainable way,” he said.

People living around Bardiya National Park are very supportive of tiger conservation efforts, but along with the increase in the number of these animals, concerns are also mounting.

“Many tourists come to see tigers, but we [yang harus] live with them,” said Samjhana, who lost her mother-in-law to a tiger attack last year.

He was mowing the grass for fodder deep within the park boundaries.

“I love her more than my own mother,” she said tearfully, holding up a photo of her mother-in-law.

“In the next few years, there will be more families suffering like mine, and the number of victims will be very high,” Samjhana warned.

In addition to exploring agricultural lands, tigers are also now entering local villages.

In March this year, Lily Chaudhary, who lives in Sainabagar Village at the end of Bardiya National Park, went to feed the pigs near her home.

The villagers found him badly injured after being attacked by a tiger, his lower body was badly torn off. He died not long after that.

“Since then, we are all afraid to go alone to feed the pigs or the cattle behind the house,” said Asmita Tharu, Chaudhary’s younger sister.

Villagers staged a number of protests after the tiger attack. (DEEPAK RAJABANSHI)

The attacks by tiger attacks that occurred triggered a number of protests by the villagers.

On June 6, people in the village of Bhadai Tharu staged a demonstration after a leopard attacked Ashmita Tharu and her husband, a week after a tiger killed another in a nearby resident’s forest.

About 300 people took to the streets to demand that the government do more to protect them.

A group of angry residents set fire to the local forestry office. When the police arrived, they were stoned.

Police forces then opened fire on the crowd and killed Nabina Chaudhary, the niece of the couple who was attacked by the leopard.

Her sister, Nabin Tharu, was a few meters away from her when it happened.

“I was about to pick up his body which was lying on the street, but the police beat people,” he said.

“My sister did nothing wrong. Is it wrong to demand security? Is it wrong to demand safety?”

Nabina Chaudary, 18, was shot by police. (Nabina Tharu)

The Nepalese government promised Nabina’s family US$16,000 in compensation and said they would build a statue to commemorate her as a martyr.

But the family demands a thorough investigation of the case.

In a letter of agreement signed by residents after the protests, the authorities promised to build more fences and walls to separate wildlife from human settlements.

In Nepal, when a tiger kills a human, the animal is caught and put in a cage. Currently, there are seven tigers referred to as ‘man-eaters’ in captivity.

“I think protecting tigers is our responsibility, at the same time, protecting humans is our duty,” said Captain Ayush Jung Bahadur Rana, as he walked home from patrol to his office.

“More tigers and more humans means more conflicts will arise. Keeping the peace between these two species will be very challenging.”

State officials are trying to find alternative livelihoods for local residents who use the national park to gather forest products or herd livestock.

They plan to develop skills so that local residents can build small businesses or work in the tourism sector.

Bhadai Tharu said his mother (right) taught him about the importance of conservation. (KEVIN KIM/BBC)

Bhadai Tharu held a meeting for the tiger conservation team.

“Misunderstanding has divided people and wildlife,” he said.

“Our forest is home to tigers. If we disturb their habitat, they will get angry. If we take our goats to graze in the forest, they will attack them.”

His team made plans to make food supplies for the livestock and create more pasture in the community forest, adjacent to the park so that the tigers had more deer to eat.

They also opened up classes for the next generation, who had to coexist with the tigers.

Children are taught about tiger behavior, and are forbidden to go into the forest alone.

When asked what their favorite animal was, many children answered tiger.

“I try to make people understand that tigers have a right to live here too,” Bhadai said.

“Why are only humans entitled?”

Additional reporting by Rama Parajuli, Kevin Kim, Rajan Parajuli and Surendra Phuyal

(nvc/nvc)

–