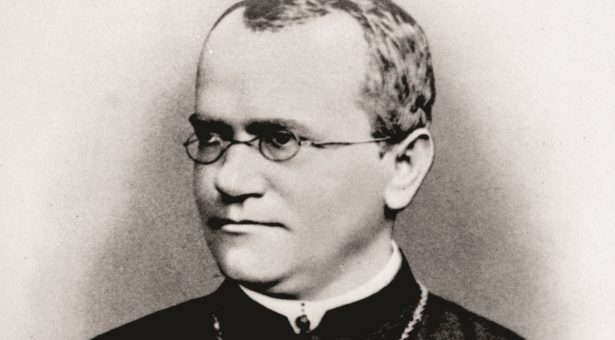

Gregor Mendel, the Moravian monk, was in fact “decades ahead of his time and truly deserves the title of ‘founder of genetics’”. So concludes an international team of scientists as Mendel’s 200th birthday approaches on July 20.

The team, from KeyGene in the Netherlands and the John Innes Center in the UK, draw on newly discovered historical information to conclude that when their proposals are examined in light of what was known about cells in the mid-19th century Mendel was decades ahead of his time.

“Discovering hidden details about Mendel helped build a picture of the scientific and intellectual environment in which he worked. At first, Mendel knew nothing about genetics and had to figure everything out on his own. The way he did it is very instructive,” he said. Dr. Noel Ellis of the John Innes Center, one of the study’s contributors.

The new information shows that Mendel began his work with the practical goals of a plant breeder, before turning to the underlying biological processes that condition hereditary differences between organisms. It also shows that Mendel recognized the importance of understanding the formation of reproductive cells and the process of fertilization.

A small but rich heritage

Mendel’s work and ideas have been studied by many, although the material describing his work is limited. Where Darwin left thousands of letters, only a few are known of Mendel.

Mendel’s work began to receive significant recognition 34 years after its publication and 16 years after his death. No notes related to this work were found. All that was left was a couple of scientific articles, one of which is the famous “Experiments on Plant Hybrids” published in German in 1866. This article is still the basis of what children in school learn about genetics today.

Newspaper articles from Mendel’s time have been digitized.

a

Thanks to modern technology, authors have been able to extract valuable information from newly digitized 19th-century newspaper articles, accounts, and yearbooks. These show how advanced Mendel’s ideas and work were when he used cell biology theory to draw conclusions about how plant traits are passed from parent to offspring.

Mendel’s element: what we call genes

Mendel pointed out that pea plants must maintain and pass on the ‘code’ for the appearance of a trait, we now call these coding instruction genes, Mendel called them ‘Element’.

For many traits, two different elements or “elements” are present, for example, to encode flower color in peas, one for purple and an alternative for white flower color.

Mendel proposed that reproductive cells containing only one type of element are formed in the male and female parts of the flower, and these single elements are passed on to a daughter plant, one from the male and one from the female.

It is now known that only half the number of chromosomes is passed on to the ovules from the female floral parts and to the pollen from the male floral parts, thanks to the division that occurs during meiosis during the formation of gametes.

Two centuries after his birth, this remarkable scientific life continues to offer new perspectives.

The article How did Mendel arrive at his discoveries? It appears in natural genetics

–