Our bodies are so complicated that even the most vital and well-studied systems still surprise.

Blood, for example, can have not one, but two types of cellular origins in forming mammalian bodies, a study in mice has just found.

“In the past, people believed that most of our blood came from a very small number of cells that eventually become blood stem cells, also known as hematopoietic stem cells.” explained Harvard University cell biologist Fernando Camargo, one of the researchers on the mouse study.

“We were surprised to find another group of progenitor cells that are not derived from stem cells. They make up most of the blood in fetal life until young adulthood, and then gradually begin to decline.” These cells are known as embryonic multipotent progenitor cells (eMPPs).

Hematopoietic stem cells are formed early in development from cells lining the arteries. Previously it was assumed that eMPPs cleave from hematopoietic stem cells early in their development.

With a recently developed genetics Barcode StrategyHarvard University biomedical scientist Sachin Patel and colleagues were able to follow dividing cells to see that hematopoietic stem cells and eMPPs arose from the same lining.

To do this, the researchers inserted pieces of easily recognizable DNA sequences at a location in the mouse cell’s genome that would be passed on to all of its cellular progeny.

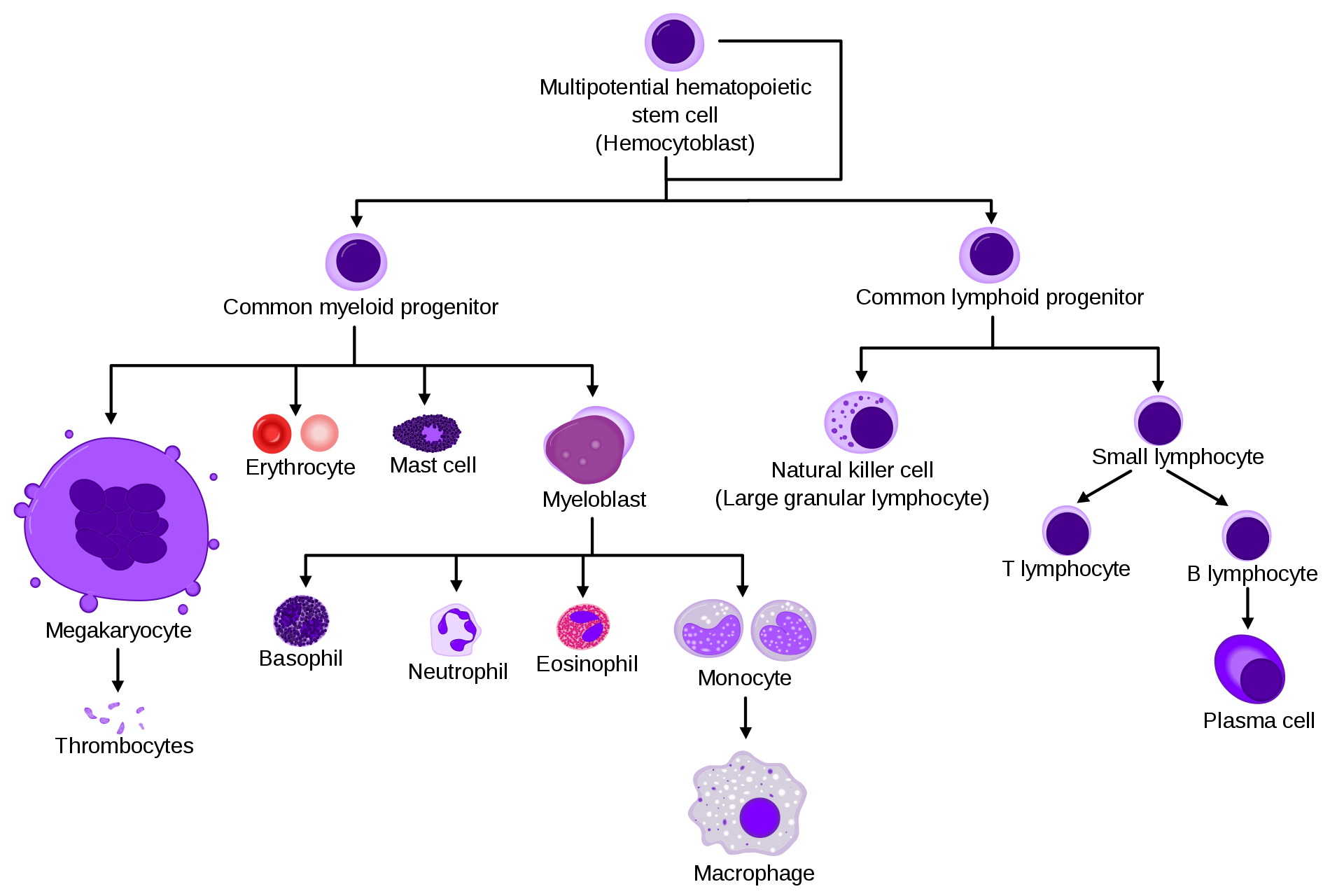

This allowed them to trace the origins of all their target cells and uncover the eMPPs, which are divided into cells responsible for most of the lymphoid cells (a type of white blood cell) in developing mice. These eMPP cells appear to be the mothers of many immune blood cells, including white blood cells (B and T cells).

Although hematopoietic stem cells can also produce these immune cells (as seen in the model below), they do so in a much more limited way. They tend to produce more cells leading to this Megakaryozyten Parts of the blood – Cells that make the components needed for blood to clot.

The blood cell lineage needs a new ancestral branch. (A. Rad & M. Häggstrom/CC-BY-SA 3.0)

“We go further to try to understand the consequences of mutations that lead to leukemia by examining their effects on both blood stem cells and eMPPs in mice,” says camargo “We want to see whether the leukemias that arise from these different cells of origin are different – lymphoid-like or myeloid-like.”

Furthermore, eMPP’s contribution to blood supply appears to dwindle over time, which may explain the long-standing mystery as to why ours Immune system weakens with age.

Patel and his team also tested how this new knowledge could improve bone marrow transplants and found that eMPP transplants didn’t last very well in the mice.

“If we could add a few genes to transplant eMPPs long-term, they could potentially be a better source for bone marrow transplantation,” explained Camargo.

“They are more common than blood stem cells in younger bone marrow donors, and they are primed to produce lymphoid cells, which could result in better immune system reconstitution and fewer post-transplant infectious complications.”

Of course, all of this only applies if the findings in humans are the same. Developmental trajectories do not always apply to different mammalian species.

The team is now studying these blood cell mothers in humans and hope their findings will lead to new treatments to boost the aging immune system.

This study was published in Nature.

–

.