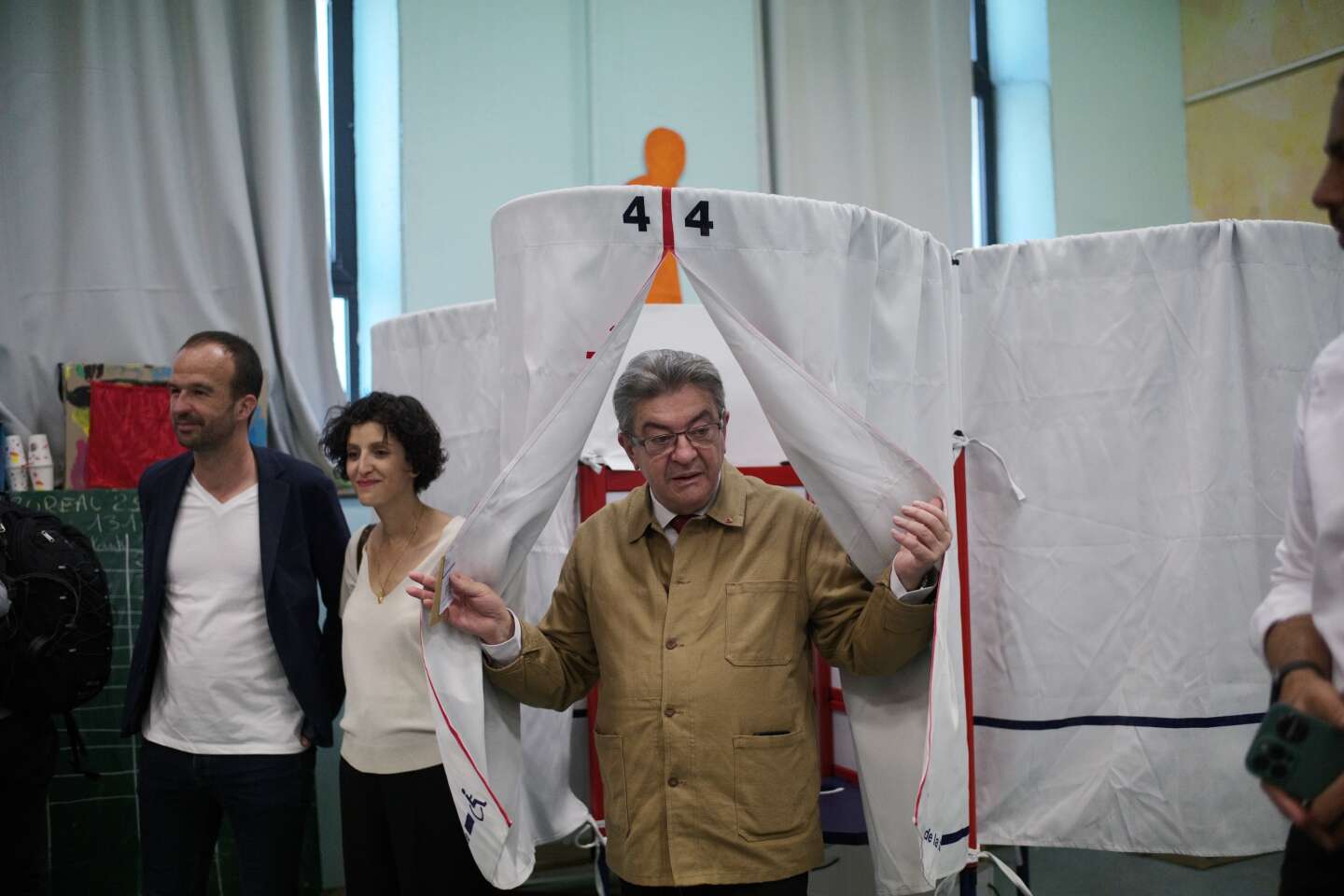

In »Atlantis«, director Valentyn Vasyanovych approaches the horrors of war with dark, post-apocalyptic images.

Foto: Best Friend Forever

–

Somewhere in the desert of southern Ukraine the car of an OSCE delegation breaks down. The translator Lukas sets out to get help and has no idea that a long odyssey through the steppe lies ahead of him. One bizarre encounter with quirky people in bizarre places follows the next, Lukas experiences violence and desperation, hospitality and even love. The young man from Kyiv, whose neatly ironed shirt grows dirtier and crumpled as the film progresses, encounters a whole new reality. “It’s total anarchy here, if you get used to it you can survive,” villager Vova explains to him.

Director Roman Bondarchuk’s film »Volcano« shows with great wit how Lukas, who initially viewed the provinces with condescending contempt, gradually came to understand how life worked there and finally became part of it himself. The atmospheric images do not embellish anything and are still a loving homage to the inhabitants of the Ukrainian steppe. »Volcano« is one of the highlights of the »Perspectives of Ukrainian Cinema« film series, which will be shown in Berlin, Hamburg and Leipzig until the end of June. A total of nine documentaries, short films and feature films can be viewed there with free admission. The selection of films reflects the diversity of the Ukrainian film landscape and gives viewers interesting insights into Ukrainian culture and society.

The war that has been raging in eastern Ukraine since 2014, before the Russian invasion began in February, is the dominant theme. The war plays a role in almost all the films shown, sometimes only as a side mention, but mostly it is the focus. The directors ask themselves how one can live in war, with war and in spite of war. What an everyday life that is characterized by danger and destruction can look like.

War has also become part of normality in the film »Territory of Empty Windows«. If you look at the current images of the destroyed streets of Mariupol, the scenes in this short documentary film are particularly touching. Director Zoya Laktionova portrays the city from the perspective of different generations and shows both the destruction of the Second World War and scenes from the present before the current invasion began: work in the steel mill, everyday encounters, tranquil scenes on the beach. The war over the separatist areas, which was only a few kilometers away, becomes an anecdote: “I was just coming from the market when they started shooting,” says a man while having tea and laughs as if it were a funny story.

In the films »Klondike« and »Atlantis«, war becomes something more existential. They show despair and hopelessness in the face of death and destruction. In »Atlantis«, director Valentyn Vasyanovych approaches the horrors of war with dark, post-apocalyptic images. It shows a future after the war: Ukraine seems to have emerged victorious and Crimea was recaptured, but large parts of the country are no longer inhabitable, the earth is full of mines, poison and corpses. »Atlantis« shows that the winners also lose a lot in war and finds frightening images of the consequences that the fighting will have long after it is over.

In her film »Klondike«, director Maryna Er Gorbach tells the story of Irka and Tolik, a young couple from Donbas. The small village they live in becomes a war front in 2014. The line of conflict runs right through the neighborhood, and there are supporters of both sides in one and the same family. The hate and violence that the film clearly shows seems even more senseless and terrible. One thing is clear: the child that Irka is expecting has no future in this place.

But there are also more hopeful films that deal with the war, such as the documentary “The Earth is Blue as an Orange,” which also portrays a family in the Donbas. The single mother made a conscious decision not to leave her hometown because someone has to stay to rebuild it afterwards, she says. Together with her daughters, she is making a film that is supposed to show life in a state of war.

The question of how to capture the war in pictures, how to tell it on film, runs through most of the films in the series. The solutions are as different as they are convincing. Director Roman Liubiy found the most direct answer. His film »War Note« consists of footage that soldiers at the front filmed themselves with cell phones, GoPros and camcorders. There are no heroic scenes, no stagings with patriotic speeches, but they show the banality of everyday life as a soldier. It’s people doing their job, which often consists of waiting for something or fixing that old rocket launcher in the backyard that’s not working properly. The soldiers don’t let themselves be spoiled: »Can I fart while you’re filming?« asks one. There is a lot of laughing and joking together. The footage of actual combat is particularly depressing in contrast to this ease. For example, the scene with the child running excitedly across a field and shouting »Mama, half our house was shot down« is something you can’t get out of your head for a long time. Also because you know that it’s just not a staging.

The films in the »Perspectives of Ukrainian Cinema« series that deal with war make it tangible because they show it from different perspectives and tell very different stories about it. Luckily, one searches in vain for bold heroic stories.

The most beautiful film in the series has nothing to do with the war and focuses entirely on the joys and horrors of everyday life. »My Thoughts are Silent« is about Vadym, a 22-year-old sound engineer who dreams of a career in music in Canada. He keeps his head above water by recording sounds for video games. For the game “Noah’s Ark” he is given the task of collecting animal noises. There is an extra fee for shooting a rare bird living in the mountains of Zakarpattia. Together with his mother, Vadym drives through western Ukraine in search of the bird. On the way, the different future plans of mother and son collide. While he is determined to emigrate, she is afraid of loneliness and demands grandchildren as soon as possible. In the bizarre, exaggerated scenes full of situation comedy, which director Antonio Lukich masterfully stages, sound and rhythm play just as important a role as they do in Vadym’s life. An unusual film that is sad and very funny at the same time.

The fact that “Perspectives of Ukrainian Cinema” also shows films that do not deal with the war makes it clear how important it is not to reduce Ukraine to the current situation. And it gives hope that at some point this war will be over and there will be room for other themes for Ukrainian filmmakers to explore with their creativity and variety of styles.

The film series can be seen in Berlin, Hamburg and Leipzig until June 30th. Admission is free. More information about the program at www.deutsche-kinemathek.de

–