In Normandy, the Mémorial pour la Paix has not been confined to the Second World War since 2002. Its director and its visitors have the impression today of seeing the reappearance of a story that we thought ended in 1989 with the fall of the wall of Berlin.

Visiting the Caen Memorial is never a cakewalk. Mean by this that the events recounted there carry their share of suffering and tragedy. And from the First World War to the attacks of September 11, humanity often does not show itself in its best light. We walk the aisles of the museum to learn and remember. But memory implies a distance. But in recent days, the line between past and present seems to be blurring somewhat.

Inaugurated in 1988, the Caen Memorial, also called the Museum for Peace, has endeavored to tell new generations about the Second World War in its entirety, from the incipient divisions to the reconciliations, a long road paved with tears and blood. . Since 2002, pages have been added to this great history book, that of the 20th century which did not stop on May 8, 1945. Photos of tanks in the streets of Budapest in 1956 or in those of Prague in 1968 thus bring visitors back to the Cold War era, an era that was believed to be over with the fall of the Berlin Wall, the remains of which are presented to the public. So many images that suddenly send back a not so distant echo. “They say you learn from history, but not necessarily. proof is“, notes gravely André Negropontes, who came to spend a holiday in Normandy. “Casually, the beginning of the second world war, it was in a country which one estimated to be far (invasion of Poland by the German army). And I feel like it’s happening again today. I’m a little afraid it’s a trigger, something bigger with an east front against the west.“

–

Keeping her distance is what Anaëlle is trying to do Sheds. “I try to follow the bulk of the action, the main information, but still staying a little further away from information that is constantly hammered out, information that is repeated, that is repeated, I avoid“, tells us this Spanish teacher. Because, as her colleague Manon Fueyo explains, “it’s something that scares me: I tell myself that in the 21st century, we are still reduced to wars.“And observing the showcases of the museum, “even if we think it’s quite far away, I have the impression that these are subjects that come up constantly.”

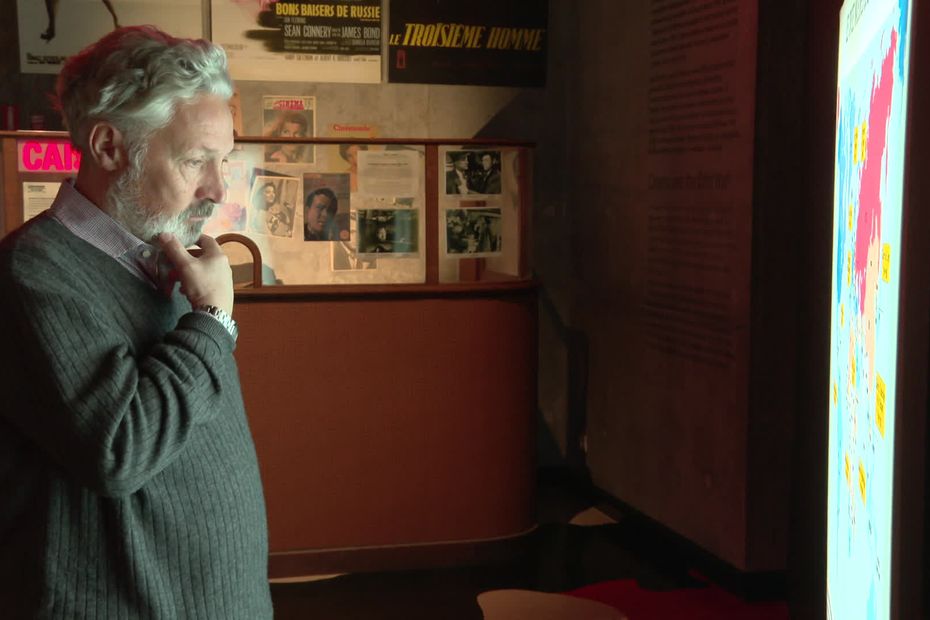

At the head of the Mémorial de Caen since 2005, Stéphane Grimaldi makes much the same observation. “What is happening in Ukraine makes me think that we have forgotten 1989, the fall of the wall, that it is already a somewhat old story and that the world is going very very quickly“, considers the director of the Museum for Peace, in view of the emotion mixed with incomprehension aroused by the Russian invasion in Ukraine. “We’re going to go back to an old storyline that we thought we’d forgotten. We can clearly see that tensions have been building up for years with Russia, we can clearly see that the same tensions are being created with China. There is a reconfiguration of the world that is taking place before our eyes. And it will last a very long time. We left for very long wars.”

–

2500 kilometers from the Museum for Peace, war is raging today. “Difficult to tell about peace. You will observe that there is no history of peace for the simple and good reason that it cannot be told.“, confided, last year, Stéphane Grimaldi to our colleagues from Ouest-France. Failing to tell the peace, it is possible to tell the war to try to understand it. “Putin is a Russian. Like many Russians, he has a nostalgia for Russian history which is not necessarily Soviet history. He remembers the history of his country, this great country, and the Black Sea is part of its geography. If we don’t see that, we also don’t really understand why they went to Ukraine. There is a Slavic world as there is a Western world. These are different worlds, which have rubbed shoulders, which have fought, loved, which have traded for centuries.“

If we can learn from history, memory can sometimes turn out to be a prison, preventing us from seeing the world evolve. “In fact, Putin is ignoring Ukraine’s recent history since 1991 when Ukraine became a nation“, explains Stéphane Grimaldi, “He ignores Ukrainian nationalism. If Ukraine is resisting – I don’t know yet how long it will resist – it is because there is a Ukrainian people who do not want this invasion of a brotherly country.” These tensions between these two former Soviet republics, the Caen Memorial has been echoing for several years now. Already in 2015, with the foundation WARM (International Foundation on Contemporary Conflicts), the Norman Museum had organized a conference devoted to the war in the Donbass in the presence of photographer Guillaume Herbaut and the journalist from World Benoît Vitkine. “What I understood, by going to this country several times, is that the Ukrainians are above all Ukrainians with, in addition, what Putin cannot stand, a real Western temptation that you see in the street, in the way which people dress, in restaurants. Kiev is a modern city that looks like all western cities“, says Stéphane Grimaldi, “The Ukrainians are people who want to get closer to Western Europe and that, Putin does not support it.” So far and yet so close.

–