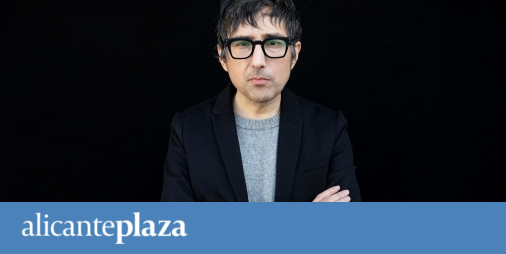

VALENCIA. He is one of the most portentous storytellers of our time. His long and poetic titles have become a house brand. Everyone guesses when a book is the work of the Argentine-Madrilenian Patricio Pron. He has won some of the most important awards in Spanish literature, including the recent Alfaguara Prize 2019 with Tomorrow we will have other names. Now publish (also in Alfaguara) Bringing it all back home a volume that brings together the stories of his last 30 years and that draws the evolution – chronologically and precisely – of a writer who already spoke of feminism in the 90s and who has dedicated part of his confinement to verifying that literature is not self-help or healing but, rather, a huge repository of lives that we will never live.

-Firstly, I am always interested in story books, how their author organizes them, under what criteria. In your case it was merely chronological and not thematic. Why?

-Someone should write in detail about the order of the books of stories that, as you point out, say as much about an author as the content of those books. For my part, I have the impression that I have been three or four different authors in recent years, with different interests, ideas and purposes, at each stage. And I thought it would be interesting if the reader of the book could meet all those authors in a single volume and decide which one they prefer, which one they like best.

-This book is 30 years of life and writing: did you correct some of them so that they all had a similar style? I imagine that you are not the same narrator today as you were in 1990.

– I am not that author of the beginnings, of course. But the first stories in the book, written between 1990 and (let’s say) 1999, are the ones I corrected the least. And that’s for three reasons: because there is nothing humiliating or shameful about being a beginner, as I was then; because I thought that perhaps readers who also write short stories will be able to identify with that young me who had the will and desire to write but still had no interlocutors or knew very well what he was doing; and finally, because it was very difficult for me to understand what I was thinking when I wrote them. I was not able to remember what exactly I wanted to do with those stories, and therefore I was not able to improve them either: it was like trying to correct someone else’s texts, something very difficult to do.

– “Narrating is making decisions,” Piglia wrote in her diaries and you remember it in the book. What kinds of decisions are made in short stories that play at a very different tension than in novels?

-The main one is, always, how to narrate a world in a few pages; what to show, what to hide and, above all, what to say that hasn’t already been said, sometimes by much better writers. It is not a question of narrative economy: in exchange for the loss of consistency in the transition from novel to story, what is gained is enormous breadth. And in that sense I would dare to say that the short story is a much freer form than the novel; at least in my practice. Quite possibly, in the short story he allows me everything, something that does not seem possible in the novels.

-You have said that the literature that interests you is the one that serves to put on the table issues about which we are not aware and I remembered, for example, the story of the lucid Argentine cow that thinks she understands everything together before everything changes, before being run over. Is that cow any of us?

-Absolutely. We have all been overwhelmed by events that we do not understand, whose dimension escapes any attempt to reduce it to a conspiracy story, an exclusively medical explanation or a matter of freedom from restrictions; but reconciling ourselves with the fact that we do not know, that we cannot know, seems impossible to some people. Perhaps what unites all the “pandemic diaries” with certain recent dystopian novels and hundreds of press editorials is that, in all of them, someone believes they “have understood”, without it being possible to know where their understanding comes from or what it is. enabled her. The last six or seven stories in this book were written during the pandemic and they propose the opposite, I would say. They try to wonder about the nature of our questions, or of certain recurring statements such as “the lesser evil”, “the greater force”, the “state of alarm” and the supposedly “exceptional” nature of the reality in which we find ourselves, and move from there towards an understanding of them that, despite being fictional, is also true in some way.

-The pandemic helped you to order the stories you had and to publish some unpublished. Was it your particular pandemic therapy?

-Not. I don’t think literature has anything to do with healing, or that it is any kind of therapy. Its character is that of things that move between what is and what could be. It is an enormous reservoir of possibilities that indicates that our ideas of gender, of nation, of identity, of ideology, are circumstantial or provisional; that we could have others, those of other people or those of some characters. There is something of that that does to the healing of our wounds as individuals and as a society; but literature is not self-help, even though some sell it as such.

-There are two elements that are repeated in the stories and that, without a doubt, are also in your style in novels: humor and surrealism. Would you say that they are your distinguishing features?

-Maybe yes. Maybe they are a product of the way I see the world, or how the world looks from here. But, in general terms, I would say that rehearsing new ways of narrating, certain experimentation that is a result of it, and the identity between narrating and thinking are what best define my work.

-In what part of the tradition of the Latin American story do you feel most comfortable, if at all?

-A writer is never the best critic of his work, not even one who, like me, works as a critic: there is a kind of myopia due to proximity that makes it impossible to answer questions like yours … While I was reviewing the stories for publication, I was surprised to discover that some things in vogue at this time such as “Latin American gothic” are present in my beginnings as a writer; I did them and then I got tired of them and stopped doing them. I suppose that puts my stories in a certain place in tradition, but only as a starting point. And the most important thing is always in which place their readers decide to place my books, what proximity they establish, where on their shelves they put my work.

-In many stories there is a look towards the feminine long before #MeToo. I don’t know if it was an issue that already worried you then and whose revolution you have followed closely.

-Well, that also surprised me: when I started there weren’t many people writing about these issues, which were perhaps dismissed as “feminine problems.” And yet I was writing about them already, apparently. I grew up surrounded by strong women like my mother and sister and I have had the opportunity to meet many others like that, and I think that made the idea that a woman owns herself always, which I would say is a central idea in my stories, even in the first ones, never seemed puzzling or surprising, as some people seem to do, even some who write. So I don’t think I had to deconstruct myself in any special way; despite which, I have followed and continue and support the struggles that women are waging at this time. But sometimes I wonder if I am not doing it, too, in the name of personal gain, since it is evident that these struggles are not intended only to improve the lives of women but that of our entire society, also that of men. That struggle is also literary, in the sense that it is a reservoir of possibilities, of possible lives, and someone will have to consider at some point how much literature there is in them, which I think is a lot.

– Finally, I would like to talk about the title that always seems a return to the intimate, to the home to the country. Does it have to do with that?

-I don’t like the idea of homeland and I don’t know anyone who up to now has been able to convince me that I have one. I have friends, I have records, I have books, I have two cats and I even have one or two passports, but homeland … Let it be the house where readers take everything …

– .