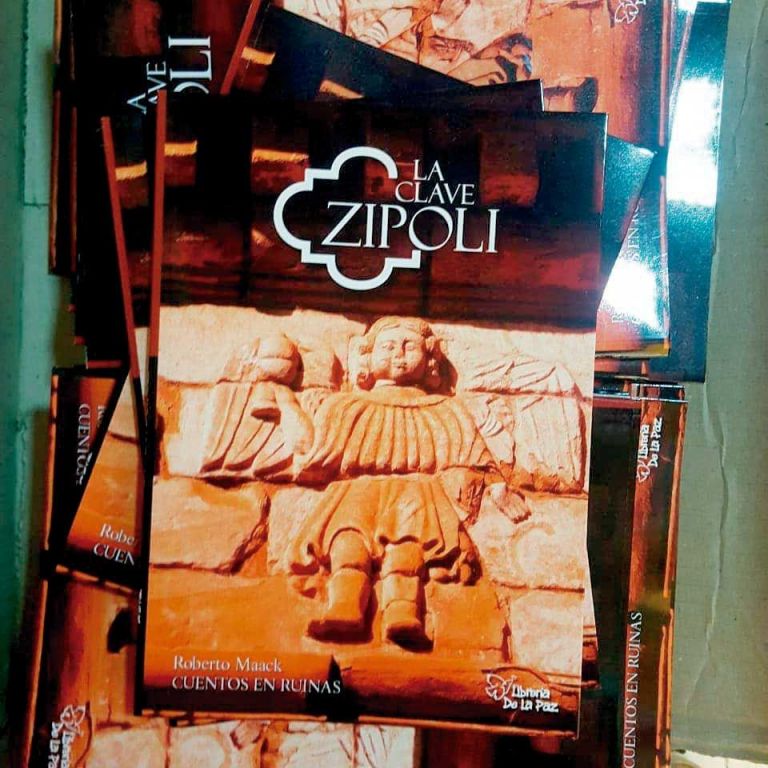

On “The Zipoli Key” – Tales in Ruins. From Roberto Maack. (Second Printing. Editions of Peace, Resistance, 2020)

Roberto Maack, an experienced journalist, knows very well about the incidents of his work, which is why the poet TS Eliot stated almost a century ago: “doing journalism is writing on the back of commercials”. With this Eliot of course alluded to the restrictions that arise from writing within the margins determined by the editorial lines of journalistic companies, in turn conditioned by various powers and advertisers.

Although in the book “The Zipoli Key” the challenge for Maack is not exactly journalistic: his intention is to recover certain aspects of the Jesuit experience in these payments, not even by appealing to a historical chronicle but by making fiction. Maack chose to enter a more winding path than that of the chronicle (although at times he appeals to that genre in this text): invent, imagine, build characters and situations, in this case around historical events. The first of the stories, “The Zipoli Key”, is woven from two unknowns that concern and occupy the Jesuit Santiago Sepúlveda, narrator and protagonist of that story: “the true reason why the Society of Jesus was expelled from these lands “, and who were” the promoters of that conspiracy “, a power that even today would subsist in the shadows. Sepúlveda’s work with the Vatican archives allows him to access valuable information on the history of the Jesuits for years, and the election of a Jesuit pope prompts him to organize a text with the results of those investigations. As a detail, the appearance in a Jesuit reduction of 5,500 musical scores is recorded, among them works by Domenico Zipoli.

After that initial narration, “The Zipoli Key”, the successive stories seem detachments, expansions of the journey in this first story that gives its name to the entire book. Or perhaps it would be more accurate to describe those subsequent stories as threads of various shades that are unraveling from a central trunk, which is the history of the Jesuits in our land. From a letter from the Guaraní caciques of Yapeyú opposing the expulsion of the priests, to the music that would emerge today in the unfinished church of a Jesuit reduction, by the hand of a mysterious violinist with the same name of an eighteenth-century Guarani musician, going through the search for an ivory crucifix of Father Roque González, a holy object from the beginnings of Christianity. Maack does not deprive himself of also doing a kind of poetic high justice act by imagining a curse that punishes the descendants of Roque González’s murderers: continuing to remember the scene of that crime through the generations. Or to imagine the melancholic story of a vase exhibited in the Loreto reduction museum, associating it with a beautiful 20th century Polish princess. Or to trace the vicissitudes of a Guaraní musician, Roquito, who returns to his hometown in San Ignacio Miní after a long and painful absence. Or to expose the sick infatuation that customs agent Cardoso suffers towards a painting of a virgin painted in a Jesuit reduction in the seventeenth century.

Like a continuity frayed in shreds then and personified in Guarani and Jesuits of different times, and in current researchers or archivists (the Jesuit Santiago Sepúlveda, the customs agent Cardoso), one finds historical books, old scores (works by Zipoli and others) , ancient paintings (the Virgin Mater Dolorosa), which sprout like unmanageable efflorescences of memory, but capable of expressing with sensitivity in plots of different types of hair two hundred years of that Jesuit project so relevant to the history of our region.

And those efflorescences that focus on art and culture – books, paintings, scores that seem to be reborn and incarnate generation after generation – a perspective of that disappeared relationship between Guarani and Jesuits, are emblematized in music: the key to reading this text That would be diverse … the key Zipoli, the greatest musician of those times. Music, a central element in the communication between Jesuits and Guarani, traverses here, in the manner of a worked stitching that spans several centuries, the various stories and characters. Like that homonymous musician of another old Guaraní musician, or that endearing Guaraní violinist who returns to his native place, the reduction of San Ignacio Miní, as an old man. And that he affirms, as a synthesis of the always ineffable spirit of music that ended up permeating the entire book: “my people are music. They do everything with songs from morning until the end of the day ”.

Mazal is a professor of Literary Theory at Unam.

–