It was not to be expected that I would come across a volcano in Karelia. In the fall I had rented a house on Lake Sjam, an eight-hour drive northeast of St. Petersburg, and soon learned that there was a volcano in the northeast. Which sounded incredible. I drove towards Petrozavodsk on Lake Onega and from there further north to the village of Girvas, in the vicinity of which one should find the “Girvas volcano”. The village itself was built in 1931 as a settlement for workers who built the dam for the Kondopoga hydropower station, one of the first in the Soviet Union. As soon as the reservoir had too much water, it was drained into a rocky gorge. When the sand layer was washed away there, a 50 by 20 meter crater was discovered in 1967 and solidified lava flows.

On the outskirts of the village you can park your vehicle, buy a one-hundred-ruble ticket (1.15 euros) and walk around the site. At the wooden fence that delimited the crater area, of course, there was no one who wanted to see my ticket, which probably had to do with the fact that there were hardly any tourists around at this time. I descended into the canyon and soon saw the coagulated gray-blue lava on the crater rim, which was sanded and worn like an old coin and shimmered pink in places. The more I saw of it, the stronger the feeling of being in an artist’s workshop. New and fascinating shapes made of cooled lava appeared and were reminiscent of bodies, heads or faces. The lava flow is said to have flowed for kilometers to the point where the city of Petrozavodsk now stands. As I left the crater area, I came across an outdoor exhibition of movie posters on the edge of the adjacent spruce forest. It turned out that this area was where feature films such as the World War II flick were filmed decades ago At dawn it is still quiet from 1972 and the adventure film The white sun of the desert, for which the first stone fell in 1970.

Supplies underground

I continue to the southeastern shore of the 250 kilometer long and almost 100 kilometer wide Onega Lake, the second largest body of water of its kind in Europe after the neighboring Lake Ladoga. In the village of Karschewo at 17a Lenin Street I move into quarters with Vasily and Klawdia, she is a saleswoman in a food store, he is a freelance tour guide. The two live in a self-built, white-paneled wooden house. For tourists like me there is a kind of log cabin with a bunk bed next to it.

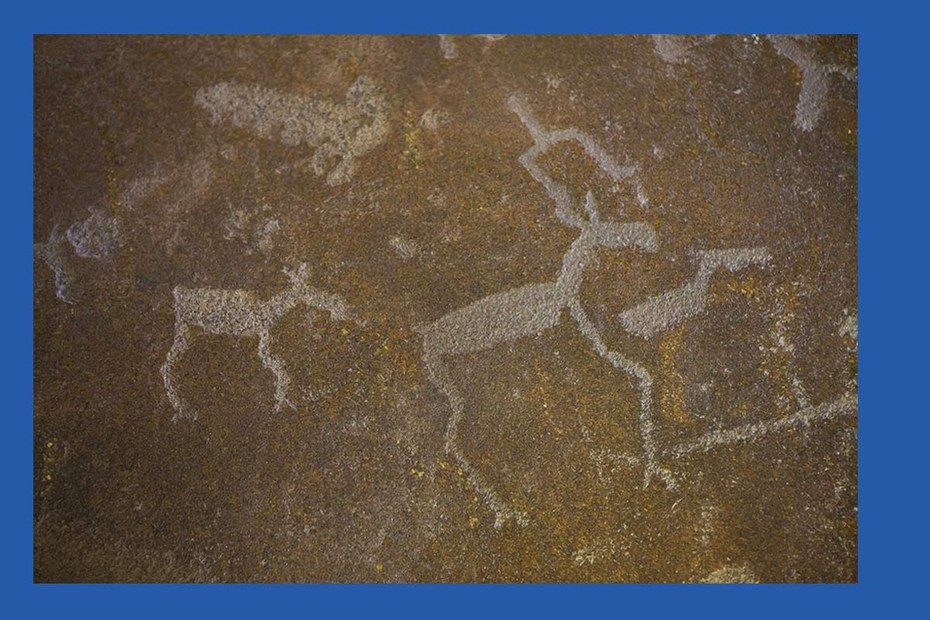

What follows is an excursion with Wassili’s motorboat to the so-called Devil’s Nose, where there are said to be rock carvings over 6,000 years old, accessible by water and marveled at on the headland of a nature reserve. Once there, I leave my tent and backpack in the boat to hike northwards along the shore under Wassili’s guidance. From time to time tourists can see fire pits, otherwise there are no signs of “civilization”, let alone cell phone networks. Instead, the waves of Lake Onega sound like a muffled orchestra to the ears of an overwhelmed city dweller. The autumn wind whips the water, but has a calming effect and carries the thoughts away from the nerve-wracking all kinds of things. We march over a wide beach, where after some climbing over rocky ledges we come to a granite massif, inside of which the drawings can be seen that were made several thousand years ago. The natives of the area have figures, but also hoofed animals, birds and swans carved and painted in the stone. Christian monks called the pictures “work of the devil”, which is where the name of the headland comes from.

Boat driver Vasily goes home and I am left alone with a fireplace and the sound of the waves, the spruce and pine trees swaying in the wind. The next morning, Vasily picks me up again as agreed. He controls an old, but sturdy vehicle made of aluminum, of the type made hundreds of thousands of times in the Soviet Union. We slide home through a winding stream towards Karschewo. Vasily asks with a joking undertone whether I have seen a bear. I say no and in the excitement over the night in the great outdoors, I forgot what Vasily said when he brought me to the “devil’s nose”. He was traveling with a group of tourists in the summer when suddenly a bear stood in front of them. It was only when everyone picked up sticks that the bear was turned off and disappeared. The last winters have been very cold and therefore the bears are always hungry, said the boat operator, who apparently is not afraid of them. In addition, a lot of forest has been cut down and the animals have lost their habitat. The wood goes to Helsinki, St. Petersburg and Moscow. Apparently, Vasily, I gather from his words, would like Karelia not only to deliver, but also to get a little more than usual.

In Karshevo I experience what it means to be self-sufficient in the Russian provinces. Wassili shows me in the garden in front of his house how he is currently building a new “Podgreb”, a cave in the earth. “Preserves” would be kept in it for the winter – jam, beetroot and tomatoes, cucumbers and onions pickled in brine. In his previous storage bunker, the support beams had rotten and a collapse could no longer be stopped. The new crypt looks like a wine cellar and not only has new planks, but also a steel frame and a brick foundation.

In addition, Wassili has installed a double door that serves as an air lock and is supposed to keep the frost out when entering. His wife Klawdia believes that in a place like Karshevo many people would live from nature by collecting mushrooms and berries and selling them in the next town. Some keep a cow, there is enough space and old stables. Catching fish with nets is strictly forbidden, but the men went fishing anyway. An indication that in Karelia up to a third of economic activity is reserved for the so-called shadow sector. The state is trying to control this domain, for example by making electronic cash registers compulsory in small shops, or by making the businesses of dacha cooperatives taxable for some time, but comprehensive supervision remains for a way of life such as self-sufficiency in the country represents, probably excluded.

Tanks and DDR tattooed

Klawdia proudly leads to her new acquisition, two calves of both sexes. They are in a small, rather dark stall. Unfortunately, they were left to their own devices early on by the mother. The animals now only get hay and water, they are fattened and not allowed to graze. The home-grown meat is still “real” meat and not as tasteless as what you get in the supermarket, asserts Klawdia. Encouraged by this, I want to buy fresh milk the evening before my departure back to Moscow. Klawdia tells me that they are being sold diagonally across the street in a wooden house that is already slightly crooked. When I step into the corridor there and shout several times, nobody is to be seen. I climb up to the first floor when suddenly a short, muscular man with a bare chest and in shorts walks towards me. He seems surprised. No, he has no milk, that is a mistake. But what is that? On the man’s right shoulder there is a large tattoo, a tank and the words “DDR” above it. I want to know whether he was stationed there. “Yes, in Wünsdorf,” says the stocky man with recognizable pride. I would have liked to know more, but he doesn’t feel like talking. At least he sends me on to the neighbor, who sells me milk in a five-liter jug.

What stands out during the tour through Karelia: The Russian state must have invested a lot in a modern road network. The slopes are often better than in the Moscow area – the nature reserves, parks, sights, hotels and campsites are reliably signposted. Apparently a flourishing tourism from the big cities and the nearby Finland is planned. The unspoiled nature of this region is an ideal area to relax. How will she survive what’s coming up next?

– .